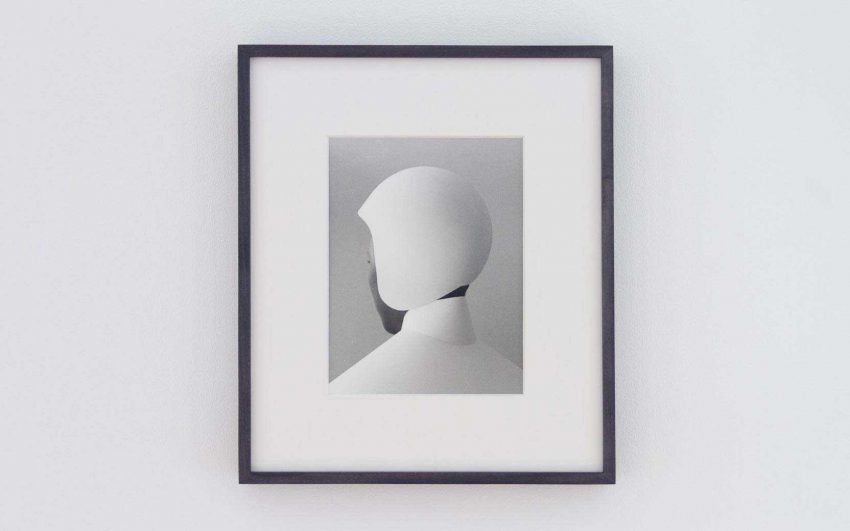

The sculptor Cäcilia Brown employs a documentary approach to her artistic practice; sculptures allow her to explore dimensions, surfaces, and even her relationship to herself and to space in a variety of ways enabling her to formulate associations. The artist uses the medium of photography to explore themes, as a way of keeping notes and an aid to visual reference, and to illustrate moods.

Cäcilia, how did you first get into art and become a professional artist?

I used to like to take photographs with an analog 35mm camera and I considered becoming a photographer. Encouraged by my brother, I applied to the University of Art and surprisingly ended up taking a sculpture course.

How do you combine photography with your sculptural work?

It's the same, only with a three-dimensional element. My sculptures are also treated in a documentary manner, whereby I can work associatively, or think further with the addition of dimension, materiality, and the relationship to myself and to space.

Do you show the photographs of your artistic research in exhibitions?

Not really. I made an exception for the group show Spuren der Zeit (Traces of Time, 2017) at the Leopold Museum. I was thinking about the presentation and also about hanging sculptures – and that automatically resulted in a wall covering – such as Die Kupferdiebin (The Copper Thief, 2017), from my series Leichte Mädchen (Floosy). The photographs from my archive could continue the chain of associations – on the panels of old election posters, on the wall.

During your residencies in Japan and China, various works created there were inspired by Japanese and Chinese cities and their architecture. Can you tell us more about them?

I have always tried to relate works that originated in another country to my mental and spatial reality. I don’t want to make postcard art, because it can be very presumptuous to be somewhere for a brief moment and attempt to talk about it in an objective way, especially if you take social conditions into account. The object excuse me now, I am here (2012) was created in part as a result of my interest in bridges. I wanted to travel on the Trans-Siberian Railway through Russia to China in order to photographically document the bridge constructions. This resulted in the series Intercity: Welcome to Parliament, which was shown in Gallery 5020 and at Gabi Senn. The Problem Roller (2015) is also connected to the journey. In the exhibition "Traces of Time" (2017), I linked various chains of thoughts, on the one hand there were considerations about hanging and the hanging works of art, as well as about cleanliness, order, and hygiene, and about value and femininity, and the right to take one's place. In the exhibition, I integrated objects that I developed in Vienna, but also my photo collection of public lavatory structures as well as photographs of the use of tiles in the public space and of rocket objects hanging in the urban space that were created in Japan.

One work that does not explicitly deal with the public space is "Collages from Conversations" (2017). What references are involved here?

Many of my references can be found in my immediate surroundings. In conversations with other people, with friends and colleagues, various topics develop that have occupied me for a long time and continue to do so. In Collages from Conversations, I discussed with Johanna Tinzl, Eva Seiler, Noële Ody, and Hannes Heel the subjects of unpunctuality, disorder and its hierarchies, men’s taxes, and the alliances of mounts. But it is not true that they have nothing to do with the public space. The conversations are screen-printed on photographic paper, and the photographs below show people who utilize metal constructions in the public space – like the boys doing synchronous pull-ups or the little group on the railing. And the conversations are also about acting in public or in the counter-public, outside the art space.

Can you name one of your works that explicitly refers to a public space in Vienna?

A good example would be my work Stadtpark, which I informally call Henry Fischinger. In this reference I play with the public space, but also the “walkable space”. The sculpture Stadtpark looks like a large, cut-out "biscuit" or a lopsided trampoline. The material refers to terrazzo floors found in representative Viennese rooms such as banks, reception rooms, and auditoriums, but also in more modest locations in more modest locations such as corridors or older caretaker apartments. I call it "caretaker marble", an interesting mundanity, considering the elaborate production of the material. The title alludes to Walter Benjamin’s "Book of Passages", which in one paragraph deals with the naming of the Metro stations in Paris, some of which bear the names of battles that Napoleon lost. Benjamin places them in relation to the underground, to the realm of the dead. The Vienna River flows underneath the Vienna subway station Stadtpark. It’s not always a case of the riverbank beneath the cobble-stones, rather I was interested in the mental connection between the upper world and the underworld, in this case literally.

Can you describe how you deal with sculptural questions and their social and political components?

There is an interest in a subject and its sculptural translation. Sculptures can be described with characteristics that allow references to the theme itself or its peculiarities. If buildings in Vienna stand half demolished for months, they inspire a sculptural interest in me, for destruction is an interesting action in itself, in this state of semi-destruction, the buildings are partially rendered into their individual materials and components. There are things that lean against and support each other, compress or smash against each other, or form piles – these are moments that I introduce into my sculptural repertoire, and I can’t avoid thinking about why so much is torn down yet at the same time, still stands. A current example are penthouse apartments, which are additionally developed and intensely advertised and sold as luxury and speculative objects. Or the demolition of old buildings in order to erect new buildings which gives rise to further questions: At whose expense are these buildings constructed? For whom are they built? Isn't the market for luxury apartments already saturated? Cities are continuously expanding and space is becoming increasingly scarce. But do these luxury penthouses really provide needed space? And how do these buildings influence the social interaction in a district?

In the exhibition "Es gibt Ecken, aus denen kommt man nicht mehr raus" (There Are Corners You Can’t Get out of Anymore, 2018) at Galerie Gabriele Senn, you refer in one work to the art of Rachel Whiteread. Can you explain why?

Sure, Rachel Whiteread created this very incisive piece on the tactics of the real estate industry in London that you can't help thinking about, yet I think there were other considerations involved. Whiteread's works receive structures, albeit as negative forms, they take up space and tell of permanence. I speak about brittleness, instability… But you can’t name a bad example, because they provoke the question whether we really want to go to London, whether we really want to give up Vienna’s quality of life that results from a mixture of social classes, strong tenants’ rights and state-controlled rents. Housing as a right, not a business model. I am talking about the fragility in this structure, about the bad connections that are being made here.

Does the role of women as artists concern you in today's art world?

I think it's impossible for a woman – regardless of the field – not to deal with this topic. I am lucky to have been born in a generation where young women are encouraged. This certainly leads to difficult conflicts that become visible for example with the quota system. Instead of helping to develop a representative quota of all society - by including all disadvantaged groups, such as people with special needs, with a migrant background, who identify as LGBTQ as well as women, it reintroduces a binary understanding of gender - man/woman. But is it a good idea to hand out a questionnaire where, as an applicant, I have to state my sexual preferences? Difficult too. I think the quota doesn’t distract from the fact that the system itself is unchanged – if, for example, an interview for the position of an art professorship continues to be held in such a way wherein applicants are thought to be convincing based upon their presentation as the loudest, the most casual, or the most self-publicizing – this may be considered to perpetuate Chauvinism. As an artist, you are subject to different working structures and risks than, for example, an office worker.

Have you ever thought about quitting your profession?

This question suggests to me a somewhat outmoded understanding of both workplace realities and the image of the artist, as if office workers today were not equally subject to precarious work circumstances. From this question I derive a very old-fashioned understanding of both work realities and the image of the artist, as if office workers today were not usually exposed to very precarious conditions.

How important is your studio to you? Do you have a special relationship to the rooms or are they purely functional?

I love having a studio. I like the way from home to home and back, on the way many problems are solved that I don’t see standing in front of the sculpture. I love the neighborhood of my metal dealer and I also like the various surrounding, their different atmospheres, I become aware that Vienna is in fact a big city after all …

I also like the studio itself, I loved the previous ones too, but to have a place that is both a home and a working space in which everything can be standing expands my own space of movement, mentally and physically. My studio colleagues and I had to renovate a lot to make the space completely suitable, and if it was also a warmer space with more light I wouldn’t complain! Ultimately, it’s about the mood of the place, if it’s good and you like going to the studio, it can be any space. As a sculptor, you are confronted with a variety of studio related practical problems including noise, storage, delivery, and ventilation.

You have lived and worked in Japan and China during your residencies. Could you imagine living permanently in Japan? How would life as a woman and artist differ fundamentally from life in Europe?

I would walk around in a kimono, eat with chopsticks, and lose 10 kg of body weight… I don’t know, but I’m always very curious and I like to live for an extended time exposed to a different culture, experiencing a different language and cuisine, I always feel excited about interacting with my fellow men.

When you think back to your early youth, which artist impressed you most?

John Lennon.

Cäcilia, if you had to describe your artistic work in a few words, what would you say?

I work on the answer to this question all the time …

Is there a misunderstanding about your work that you would like to correct?

No, but hang it up on a nail for future consideration…

Finally, I would like to ask you what you are currently working on.

On the task to describe my work in a few words.

Interview: Alexandra-Maria Toth

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt