This story has emerged in cooperation with Art Source, a unique online platform that provides exclusive access to discover and collect Israeli art. Deeply immersed in the local art scene, Art Source creates an online home for anyone who wants to take part in the contemporary Israeli art community. Art Source’s services also include art advisory and bespoke art tours of Tel Aviv’s art and design scene.

The Israeli art scene is densely populated by established artists, whose work is often a direct response to the tension-fraught reality around them. A young generation of artists aims to take the creative conversation to new, previously uncharted territories: Ones that tell the stories of our times and refuse to be confined solely to the context of the conflict. One such refreshing voice in the contemporary art scene is that of 27-year-old painter Daniel Oksenberg who works in Tel Aviv. In his richly-colored, abstract paintings, he casts his gaze on trivial subject matters. Using his canvas as a launchpad for emotional and anthropological research, he zeroes in on seemingly mundane objects, coaxing out their secrets. For Oksenberg, a fence encircling a public park or the padding of a bus seat are just as fascinating topics as war and heartbreak. In his sun-dappled studio, nestled in the heart of Kiryat Hamelacha – a growing hub of arts in the south of the metropolis – we learn what what it is that attracts him to the banal, and how he manages to extract from it its magic, and about the softly spoken stories of objects.

Daniel, I want to start by asking you to take me to the very beginning: How did you start making art? Was there a specific moment that you remember in your life that triggered the desire to craft, or a person who steered you in that direction?

It’s a little funny, I always knew I would find myself in the art world. I grew up in a very creative household; my mother is a graphic designer and my father is an architect, so there was always some connection to art in my house. I knew I would make art, I can’t quite explain this feeling. I thought that I would either end up being an artist or a mad scientist (laughs).

The two are not that different from each other.

Totally! Eventually, I decided to make art because art enables me to do and be everything I want. Over the years I grew to understand that there are many ways of life that would allow me to be who I want to be, but there is something in me that is able to understand myself better by observing other characters, which is what I do in my art.

Was there anyone who helped you arrive at the decision?

No, I was very independent. I knew I would study at the Bezalel Academy of the Arts in Jerusalem. My parents are alumni of the academy.

That’s rare, not every artist knows this from such a young age. If I were to ask you to describe your art these days in a few sentences, how would you put it into words?

I examine still life, which becomes very alive – both in the sense that objects become symbolic, and in the sense that I understand that these objects have a history, they tell a story. All the small knick-knacks we collect in life that remind us of experiences and memories have a sentimental value. I also look at the places where painting interfaces with life itself; when the painting creates an environment, kind of like a theater set. I like to make room for stories to tell themselves. So if I had to be even more precise, I would say that there is a connection between how I look at the potential objects have of telling a story, and the way in which painting expresses that story.

So for you it’s a meeting point between these two places?

Yes, the meeting point between history and the recreation of reality. Interesting, I never described it to myself that way.

Then it’s great we’re talking about it now! Tell me, are there any artists or specific artworks that for you are a source of inspiration, an icon or something to correspond with in your own work?

I don’t feel that I correspond with other artists in my own work, but they are always somewhere on my mind. Cy Twombly is an artist I really love, I find myself looking at his works a lot. When I went to see his retrospective at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, it was the first time I understood what it meant to be moved to tears by a painting. It was a very strong experience. I am also very into minimalistic sculpting, I really love Robert Morris’ sculptures. A local artist that inspires me a lot is Guy Yanai.

I share your love for Twombly very much. Speaking of corresponding (or not), do you feel that your artwork corresponds with the place you live in? Tel Aviv, or Israel at large? As an artist operating in this country, you are surrounded by a complicated geopolitical reality.

I always take images and stories from my own life into my art, and I live here, so there is a connection to reality and to life in Israel. Some of the images I paint are very recognizable for their so-called ‘Israeliness’: Whether it be an electric antenna or a bus. Politically, I am preoccupied with contents that have less to do with who will head our next government, and more connected to concrete, everyday things: Love, death, disappointment.

The light matters of life (laughing). Is there one specific theme that you think defines your craft more than others?

Probably memories. The tension between home and the outside world. Love. These are very big words, I’m not sure they do justice to how I feel. It’s mostly an attempt to connect to a feeling or a poetic meaning behind things, and through painting to unveil something about our reality that we may know but don’t pay attention to.

Do you think that people see that in your art, or that they miss out on this more subtle layer if they don’t look closely enough? I ask this because your paintings are primarily very colorful and aesthetic.

Maybe, but I believe that even if an encounter with something lasts only a minute, it does leave an impact. Many of my works are borderline abstract, so people don’t always understand what they are looking at. So someone could look at my painting and not get it, and then when I point out what the object is they suddenly go: ‘Oh, wait, wow. I see it now!’ Or they discover it on their own, and then it’s beautiful to see how the familiar object turns into something foreign in the viewer’s eyes.

It’s like treading familiar territory and suddenly not recognizing the ground you are walking on.

Yes, and not recognizing it allows you to see it from a different perspective. You can suddenly process things, see the material. If I paint with opaque materials, it’s not the same as painting with transparent materials. Or sometimes I scratch the surface of the canvas, and that in itself is a violent action. So the new perspective I try to create works on several levels.

Do you think that makes the interaction with your artwork more complicated?

I started from a place where everything was very immediate, I just created. Slowly, with time, I demand more of my viewers.

I think it’s because you are beginning to develop a more complex visual language. It’s interesting to follow that process with an artist, from their beginning to the middle of their career.

I hope so.

So what are you demanding of your viewer today? What are you working on now?

I’m working on a series of flowers, both in painting and on prints. It’s a bit in line with my interest in still life; there was a time I painted a lot of fruit, so now I’m painting flowers. What I love about them is that they’re a little bit like faces, or lipstick marks left behind after a kiss. This is a romantic image, but I see them a bit as monsters.

How did you become fascinated by flowers?

My grandfather always grew flowers in the garden of his home in South Africa. He had a rose garden that people would travel to his street just so they could see it. So the image stuck with me, and flowers have accompanied me since childhood. I paint them with industrial paint, which kind of throws you out of the frame because of its texture, but there is something about the flowers themselves that really sucks you in.

They look a bit like Rorschach inkblots.

I’m glad you see that. These paintings, which I’ve been working on for about a year now, are about the places where you can find yourself or other faces reflected. Flowers are a complicated thing, they are tightly wrapped into themselves. Maybe it’s a bit like a psychological tangle I am trying to undo.

I wonder where they will take you next. It seems like you’re very prolific and getting recognition from the local art scene; you’ve exhibited your works in solo shows and in group exhibitions in galleries all over. Do you feel the pressure to prove yourself? Does it interfere with your work?

There are challenges. When I left school I immediately started working. I was glad to graduate and I had no fear. I was very motivated to create and see art. I immediately found a studio and got down to work. I’m an artist, and it’s my job to be an artist. It’s crucial for me. If I don’t paint or think about painting, I get depressed. It consumes every moment of my life, and everything I see activates that in me.

So what does your routine in the studio look like? It seems like you’re producing paintings nonstop.

My work process changes from time to time. There are periods when I paint a lot, and there are periods where I think, digest, experience what I need to paint. I love being in the studio, even if I’m not holding the paintbrush in my hand I am reading, looking out the window, staring into space. It’s all part of creating.

One of your main methods is going out into the street, wandering and taking pictures with your smartphone of things that grab your attention. You then use these images as a reference point. So I assume that your geographical location impacts your creative process.

The physical space where I am influences me. Sometimes it determines how large a painting will be, sometimes it affects how I display things in space. For example, when I exhibited my work at an exhibition space in Tel Aviv called Third Floor on the Left, which was literally in the curator’s apartment, I couldn’t hang paintings on the walls so I created these installations that became part of the space and changed it. It’s interesting to see how a painting becomes three-dimensional in that sense. In the past, I used to take pictures and then break up their elements by painting them. Today I still learn from photography, but the content and the feeling taking precedence over accuracy. So now photography acts as a memory-keeper of sorts in the larger process.

What else inspires you, apart from photography?

My own personal history and memories are sources of inspiration. I love literature, poetry and theater. But I can find inspiration in anything. It mostly stems from my inner world.

You know, when I look at your paintings I often think about the connection one has to one’s home, the individual grappling with their roots and the place they come from. You use very warm colors, but evoke a rather sad sentiment. Is that something you are aware of? Do you wish to convey it in your work?

What’s beautiful about art is that it stretches the limit between the conscious and the subconscious. I’m very aware of the fact that I’m preoccupied with the concept of home and losing one’s home, but I’m also always surprised by how much my work expresses that. Throughout my life I moved around a lot, and the notion of home or lack thereof is always at the center. Recently my parents sold my childhood home, and that caught me off guard. I often search for a home in my craft, a place that will contain me. Fruits and flowers, which I draw a lot, are things you generally find in a bowl at home. My subject matters belong to that private space.

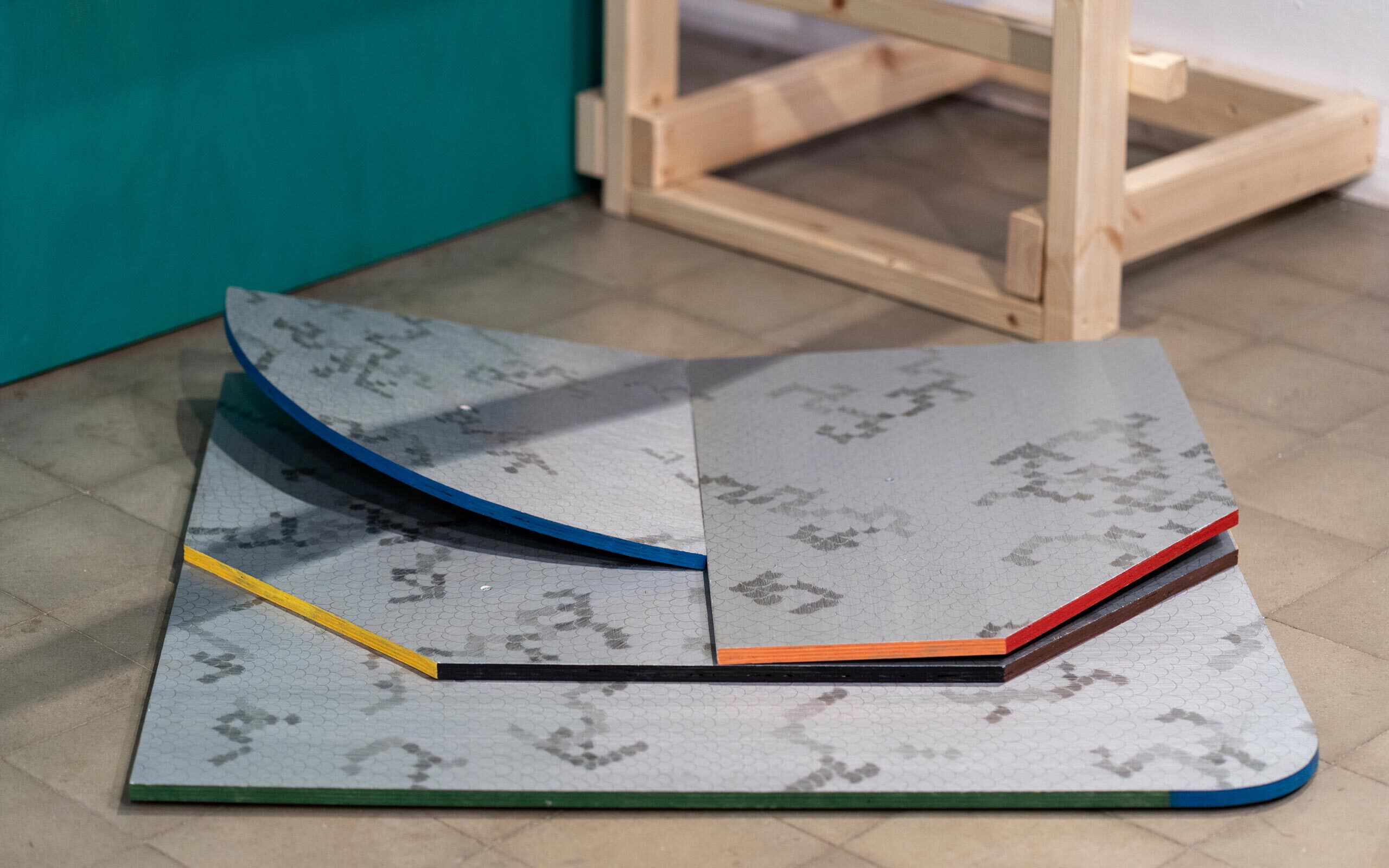

Sun Scorched Pavement, a printed quilt industrial paint and enamel paint on plywood, 190x280x260 cm, 2019, Barbur Gallery Jerusalem, Israel, Photo: Daniel Hanoch

Crumpled Traffic Sign, industrial paint and pencil on plywood, 30x100x90 cm, 2019, Barbur Gallery Jerusalem, Israel, Photo: Daniel Hanoch

Reebok, oil paint on plywood, 250x280 cm, 2018, Third Floor on the Left, Gallery Tel Aviv, Israel, Photo: Flora Deborah

He Who Fell but Couldn't Tell If He Even Tried to Resist, exhibition view, 2019, Barbur Gallery Jerusalem, Israel, Photo: Daniel Hanoch

Interview: Joy Bernard

Photos: Flora Deborah

Links: