Based in Paris, multi-disciplinary artist Laëtitia Badaut Haussmann explores an expanse of themes that range from feminism to domesticity, para-architecture to psychology. Focused on creating immersive, multilayered installations over individual, easily commodifiable art works, she often turns to literature and cinema to guide the extensive research that informs her practice. We spoke to Laëtitia about phantasmagorical smoking rooms, feminist architecture, and why she’s a big fan of grandmothers.

Laëtitia, when did you first become interested in art? Who were some of the first artists that inspired you?

I think I’ve always been interested in art. I don’t remember making a specific decision to engage with it. When I was younger, I was always surrounded by paintings. One side of my family was really into classical art, whereas, on the other side, I had a grandmother who had crazy posters of works by Dali and Mondrian. I think the Dali one was very strange to me when I was a kid, so I looked at it constantly. I’m not necessarily a big fan of Dali now, but there’s something about how he questions levels of representation, time, and space which have definitely influenced me as an artist.

When did you start making your own work?

I remember being very young and writing a poem with my left hand, even though I’m right handed. It felt like some kind of performance. This is a really strong memory and it feels significant in some way, as a kind of starting point. I’ve always been very interested in space: its organisation, its circulation, its transformation. For me, starting to create art was more about relating to my environment in a specific way rather than drawing or painting.

Who encouraged your creativity?

My family always, very graciously, encouraged me to do something other than art. This said, they have always supported me. Fine Art schools in France are public and are very difficult to get into, but an ex-boyfriend’s aunt really encouraged me to pursue this path. She was an amazing woman!

You studied at École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts in Paris-Cergy. How did your time there inform your development as an artist?

I was determined to attend this school. It was established shortly after May 68 the founders really wanted to make a statement by taking a more conceptual approach, being more transdisciplinary, and basing the school on the outskirts of Paris. While I was there, I didn’t have to choose one specific studio to belong to: the school was organised very differently to traditional art academies and I was allowed to take classes in film and dance as well as painting and sculpture and so on. The opportunity to mix different interests was invaluable for me, especially as I’ve always been interested in the topic of environment, setting, and set design in relation to the realms of dance, theatre, and even more so cinema. I grew up watching tons of films from all different genres, so cinema has always been creatively and intellectually inspiring for me. Being at École Nationale Supérieure d’Arts allowed me somehow to get as close to cinema as possible, without actually making cinema.

How would you describe your practice in a few sentences?

I’m very much research-based. Context, history, and the intellectual process behind my work is key. This said, I’m also driven by shape, colour, and materials. The idea, and challenge, is to develop a synthesis, or crystallisation of all my research.

When I speak about context, I’m referring to all the layers of cultural, social and political discussion with curators, institutions or spaces where I am showing my work. Architecture is fundamental for me.

“Para-architecture” is an important element of your work. What does this actually mean?

The concept of para-architecture was formulated by Daniel Marcus, a Columbus, Ohio-based curator and art historian who is also a good friend of mine. I worked with him a lot between 2017-2020. To put it simply, para-architecture is the consideration of all things that surround “pure” architecture: not only the development of buildings, but also internal spaces, how people experience them, and even the organisation of whole cities. To me, everything comes back to architecture. Cinema is architecture. The Lebanese-American poet Etel Adnan explained it very well in a 2011 interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist. She said: “Architecture is a form of elevation, a vertical movement, something that grows out of the ground like a tree that grows. Architecture encompasses everything: form, colours, social concerns. In the end, it is always for human beings, whether they occupy the buildings or walk through them. It is both a mysterious art form and our habitat. We cannot escape it. Even a tent is architecture, and even a cave if it is inhabited.” I also often refer to Ludger Schwarte’s words in Philosophy of Architecture.

Can you describe some other themes that permeate your practice?

Domesticity is an important topic for me. A few years ago I worked on a very long series called Maison Francaises, une collection. It featured around 60 photographs appropriating advertising images of pieces of furniture from the 70s, 80s, and 90s. I erased all the text from the advertisements to see what messages they conveyed on their own without the assistance of language. I also wanted to see what would happen if they were placed in a new context—on a gallery wall—allowing the images to have a different treatment to their original purpose. Many amazing female artists work with the topic of domesticity, such as Martha Rosler and Dominique Gonzales-Foerster. The latter works with different types of spaces, mental and physical, in response to the multiple meanings they have in literary works by the likes of Virginia Woolf and Nathaniel Hawthorn. Gonzalez-Foerster is a very important reference for me. I looked at her work a lot when I was a student, and still do today. I’m also very interested in the American artist Barbara Bloom, who works with furniture as a way of exploring concepts of power and political moments in history.

Light my lucky, seconde, 2018, Performance view, Festival MOVE, Centre Pompidou, 2018, Courtesy of the artist, Photo: Hervé Veronèse

Feminism is another important concern for you, right?

Definitely. For a few years I’ve been exploring the concept of feminist architecture. How could we categorise it? Can we observe historic architecture as feminist? Or what does unfeminist architecture look like? I’ve started researching this topic using film and cinema to support my thinking.

Is this also the topic of your current residency at Secession in Vienna?

I’m actually going to be exploring something different, but it’s still connected. I was initially inspired by Tabak Trafik, an old Austrian tobacco brand. I love the logo: I have a t-shirt with it on that I bought from a flea market in Japan that actually initiated the idea for this project! I’m very interested in the fact that for a long time the production of cigarettes in Austria was nationalised. I’m curious about the history and trajectory of cigarettes, the concept of smoke as a social and binding element, how this relates to a very specific point in history in Vienna, the cafe culture there, and therefore psychology, psychotherapy, and abstraction. A huge quantity of women have contracted lung cancer because of smoking. The number of cases is reaching critical levels. In Adam Curtis’ 2002 film The Century of the Self, he talks about the fact that in the beginning, cigarettes were seen as more masculine objects. At the beginning of the 19th or 20th century, companies rebranded them as synonymous with female emancipation and liberation. They became a real tool and statement for women. I’m really interested in this kind of capitalist, patriarchal trap.

What do you want this research to develop into? What will the end product be?

I’d love to create some kind of phantasmagoric smoking room featuring elements from the Tabak Trafik archives as well as new creations. I want to spend a lot of time in Vienna’s streets and take documentary photographs of people smoking. Physically being in the city is going to really affect the outcome of the project because it’s very important for me to completely immerse myself in the topics I’m working with. Without immersing myself, I can’t properly articulate myself. I need to be in the presence of things to be able to process them. I’m a very slow person, I can’t react to things quickly. I have to observe, absorb, and process before I know how I want to respond.

This immersive smoking room idea reflects the fact that, while you work with mediums including sculpture, installation, image, and text, your primary concern is exhibition making. Why?

It may be a bit of a contradiction but I don’t think I’m a very materialistic person. I think I’m more interested in being able to leave everything in movement, and working with fluidity, the transformation of environments, and experiences, rather than fragmented elements. The immersive aspect of installations also allows you to somehow bypass the commodification of art.

Seins - montagnes - sable - ruines (1), 2019, Sand, Dimensions variable, Exhibition view, “Water", Cur. Jo-ey Tang, Beeler Gallery, Columbus, Ohio, USA, 2019-2020, Courtesy of the artist, Photo: Stephen Takacs

Seins - montagnes - sable - ruines (2), 2019, Sand, Ikea furnitures, divers objects produced in Japan, Dimensions variable, Exhibition view, “Water", Cur. Jo-ey Tang, Beeler Gallery, Columbus, Ohio, USA, 2019-2020, Courtesy of the artist, Photo: Stephen Takacs

For you, what makes a good exhibition?

Courage, radicality, and the feeling that someone has pushed the boundaries of their work as far as possible. This question has immediately made me think about Gut Health, a show by my friend Hanne Lippard that was shown at The Pharmacy Museum as part of Art Basel. It was very sharp, humorous, and simple. I think those are all important elements of an exhibition.

Tell me about your most recent solo exhibition, As if a house should be conceived for the pleasure of the eye, she says, which was shown at Ellen de Bruijne Projects in Amsterdam last October (2021). It was partially inspired by themes from Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, right?

The starting point of the show was the concept of feminist architecture that I mentioned earlier. I based my research on two films: Barbet Schroeder’s Maîtresse (1976) and Todd Haynes’s Safe (1995). I was very interested in the female characters’ relationships with the architecture surrounding them, and how, in both films, it was almost like an important character in its own right. In Maîtresse, the main character is a dominatrix: she has a dungeon just below her apartment. This extra room was very interesting for me. In BDSM, these spaces are places of trust, transformation, fiction, and where domination and submission are played, reversed, and expanded. They’re spaces of total freedom as well as of total desire. I was interested in how we might be able to perceive these spaces beyond their primary functions. I watched and worked with Safe during the first coronavirus lockdown, so the idea of being in an enclosed space was very relevant at that time. At the end of the film, the main character finds shelter in a new age therapy centre. The architecture there is geodesic and very ambiguous. This inspired me to work on some architectural models as a way of thinking and processing the film’s themes. Finally, coming back to the Virginia Woolf text, I also wondered: in today’s society, do women need more space, or do we actually need whole cities to be rethought and reorganised?

To take the topic of A Room of One’s Own in a different direction, what is your studio space like? How is it set up to be conducive to your artistic practice?

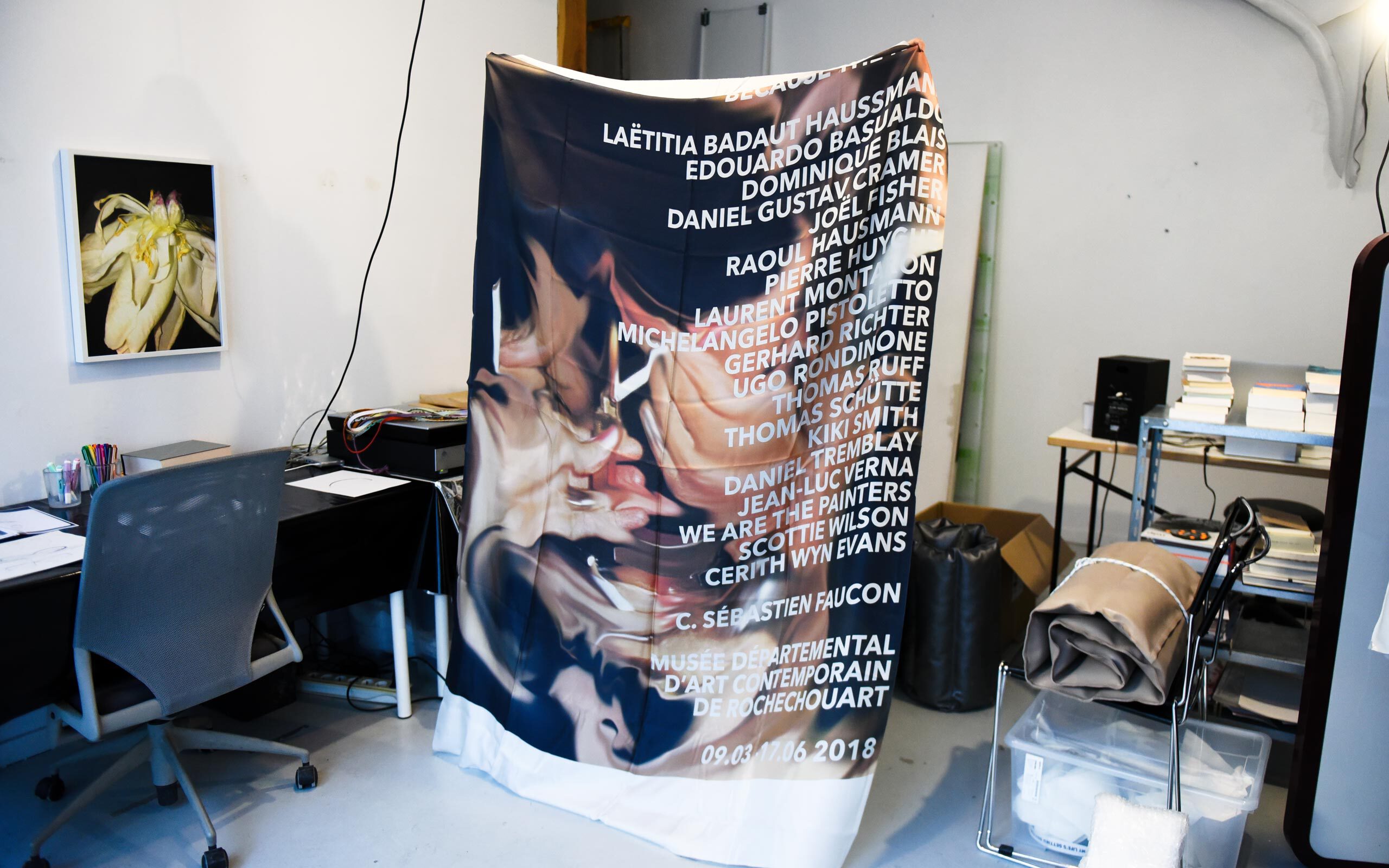

I spend a lot of time in my studio, I love being here. I change the space all the time depending on the project I’m working on. Right now it’s very clean. There are mostly books, tables, and my scanner, so I can really dig into my research. Last month, it was much more of a painting studio. I was showing new paintings and sculptures inspired by screens and room dividers as part of a group show. It was very messy.

Do you think there are any misunderstandings people have about your work that you’d like to address?

Some people think my work is about questioning design and the production of form. Some think that it can almost be seen as a piece of design itself, which is not quite true. Even though the shapes and forms in my work can be very strong, my starting points are very conceptual.

To finish, do you have any artistic heroes that you’d like to pay homage to?

While she’s very far away from my own practice, I really admire the Lebanese-American artist Simone Fattal. I’ve had the chance to meet her a few times, and we were both nominated for the same prize once. One important person with whom I continually discuss work and life, and who I absolutely admire, is the British artist Anthea Hamilton. Jenni Crain, who was an amazing artist and curator, sadly passed away last year. She should be remembered. Finally, I love Linda Nochlin and her granddaughter, Julia Trotta, who is a very good friend of mine. I’m a big fan of my friend for obvious reasons, but I’m also in awe of the relationship she had with her grandmother. Their bond was a source of inspiration: it combined feministmentorship, art history, and familial filiation surrounded by love. My grandmother was one of my personal heroes too. I love grandmothers. I’m a big fan of grandmothers.

Love Sculpture (falling), 2021, Metal sculpture, soft leather, fleece, 105 x 121 cm (approx.), Exhibition view, “As if a house should be conceived for the pleasure of the eye, she says”, Ellen de Bruijne Projects, Amsterdam, NL, 2021, Courtesy of the artist, Photo: JdS

Magnetic Scans, 2021, 4 color inkjet prints on Epson Matte Superior paper, 31,9 x 46 cm, 40,21 x 46 cm, 7,91 x 46 cm, 25,5 x 46 cm, Exhibition view, “As if a house should be conceived for the pleasure of the eye, she says”, Ellen de Bruijn Projects, Amsterdam, NL, 2021, Courtesy of the artist, Photo: JdS

Magnetic Scans, 2021, 4 color inkjet prints on Epson Matte Superior paper, 31,9 x 46 cm, 40,21 x 46 cm, 7,91 x 46 cm, 25,5 x 46 cm, Exhibition view, “As if a house should be conceived for the pleasure of the eye, she says”, Ellen de Bruijn Projects, Amsterdam, NL, 2021, Courtesy of the artist, Photo: JdS

Maquette (Safe), 2020, 80 x 40 cm, Polystyrene, tadelakt, aluminium, inox, Exhibition view, “Lucy Jordan”, Galerie Allen, Paris, France, 2020, Courtesy of the artist, Photo : Aurélien Mole

Interview: Emily May

Photos: Elise Toïdé