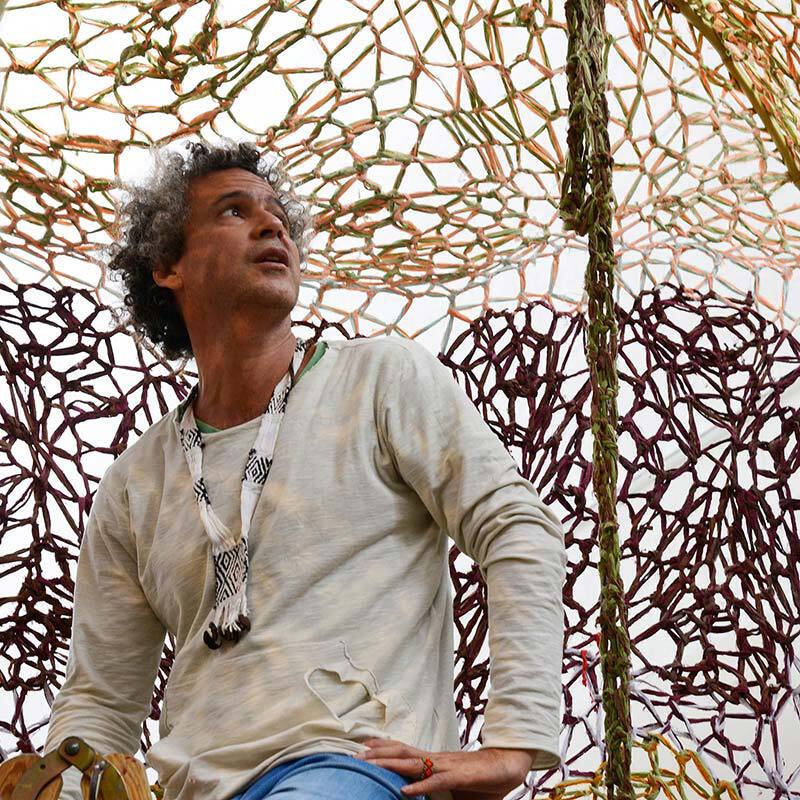

Mario Kiesenhofer works with photography, video, text and installation. He focuses on the representation of queer communities and their safe spaces in art and society. Kiesenhofer created a series of work in Eastern Europe, where he shines a light on the queer rave scene in order to undermine the narratives controlled by right-wing politicians. The artist studied photography and video art at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, the city in which he now lives.

How did you become an artist?

I've always thought with my eyes. That's why this classic idea of the artist who draws and paints, who absolutely has to use his hands to create, annoyed me. For me, nothing is as relevant as the eye. Therefore, photography was my natural medium.

In your work, you deal with queer spaces; how come?

That has to do with the way I grew up. The question of queer or gay spaces came up pretty quickly for me. I grew up in the countryside, where those didn't exist. The question that preoccupied me was: Where is the space in which I can explore myself?

Was this search for space also a search for security?

If you grow up queer or gay like me, you are automatically being seen in a different way. There are insults that inscribe themselves into your body as shame, and you have to become resilient to them. Moving to the city was the obvious way for me to escape the judgement and rejection of my rural surroundings. Didier Eribon describes this very well in his Insult and the Making of the Gay Self in the chapter The Flight to the City.

Did you experience Vienna as open? It still is a relatively small city...

Yes, but Vienna has institutions, bars and universities that offer a different view of the world. It attracts people who might not feel comfortable in the countryside. And this togetherness results in a chosen family and offers safe spaces. Suddenly, I could see the world from another angle. That was when I realised that I wanted to show my view of the world and what I felt was missing into my work.

Is that the premise of your work?

Yes. When I think about what images I want to put out there, I ask myself: what kind of visual discourse is still needed? I put my perspective and my experience into my work because I think that queer representation is still much needed in art and society.

Are you checking out what other artists produce on these topics?

Very much. I travel a lot, I see many exhibitions, I do tons of research. There are organisations like ‘Queer Art New York’; for instance, they have invited me to take part in their digital residency. In general, however, I find it difficult to categorise art, for example into feminist or queer art. Ultimately, the human being is always at the centre of art. In my opinion, minority rights conern society as a whole.

How do you manage to elevate your art from the personal to the universal?

Formal decisions play a role here, such as how I deal with space and how I open up topics. Dialogue is important. How do I approach the subject, how do I communicate it, with which text, with which language?

Therefore you are using a conceptual approach?

Of course. All of my work always follows a conceptual approach, in combination with my photographic perspective. This gaze is usually very formal. The composition and how things relate to each other in space play a major role for me. Every picture I take, and how I decide to display it, has a deeper meaning. This could be Derrida's theory of the Parergon, for example. He describes the frame as something that is not the main part of the artwork, but a tool that influences its meaning and interpretation by both enclosing and delimiting the work. I am interested in where the space ends and the artwork begins, and where this boundary becomes blurred.

Speaking of display: I feel that you give your work an extra level through its presentation...

Yes, for me, photography as just a print is not enough. That's why there's always an element - the display, for example - that adds a layer, a content-related component. Just paying attention to aesthetics doesn’t cut it.

For you, display means not just the frame, but the presentation itself. In your exhibition at Smolka Contemporary, for example, fog floated through the space...

Exactly. I work with topics and people that deserve protection, or that have a certain fragility. That's why I use specific visual strategies. It can be a frame with frosted glass, which makes the print appear fuzzy, or fog, which actually blurs the boundary between space and art. In the Treasure series, which valorises a queer minority, I use chrome frames to make the portraits shine.

Therefore these elements are part of your work?

Yes, this is why these photographs are only available in my frames. I think what is special about my work is that it always offers this combination, which makes it formally strong.

You mentioned that your work is mostly about people deserving protection. On the other hand, you also photograph metal struts or empty rooms…

For my Indoor series, I photographed gay cruising clubs outside opening hours. The sculptural quality of these spaces interests me. The appearance of these special places is similar worldwide, it is somewhat hyper-masculine. Among other things, I wanted to explore how this shines through in the material and in the architecture.

Are these so-called “gay spaces” still in keeping with the times?

I ask myself the same question. On one hand, it's important for the community to have gay cruising spaces where people can be among themselves and feel safe. But gender is now perceived as much more fluid in public discourse. And some of these places are still characterised by binary gender concepts, which again creates exclusion.

Right now, one often sees art that has something documentary about it. How do you feel about this intersection?

That's always the question with photography, of course. When is it a document, when is it art? Especially in relation to my work. Am I simply documenting the queer rave scene? No. I'm not trying to document something in the sense of a report, but rather to name it. I evaluate it, I elevate it.

Is that why all your works have titles?

Yes, the title of the Treasure series, in which I portray queer club scenes in Eastern Europe, signifies a clear valorisation. It's about reversing negative external attributions. And that's the artistic break, meaning that my work doesn't just have a documentary approach, but rather a creative one.

Do you sometimes worry to be pigeonholed because of your work - as the artist who portrays queer people?

External categorisation happens automatically. And even more so if you're queer. At some point, I had to let go and I decided that I should just confidently do what I want to do. That what I say is relevant. I can't control what other people think about my work. In the end, the heart of my art is that it really is mine.

Recently you have been photographing in Poland and Hungary. Were you after capturing a political aspect of queerness?

I think my work has always been political, even if not at first glance. The private sphere becomes political as soon as you open up. My work is often about hidden, sometimes unwanted spaces.

But why Eastern Europe in particular?

Before, I had been travelling frequently to Tokyo, New York, Paris and London, to these westernised cities that already have a queer infrastructure. But then I started to pay more attention to what was happening in my immediate surroundings, especially the shift to the right in Europe. That's how I came across Poland, where LGBT-free zones had been proclaimed by local politicians during the PiS party's rule, and had been supported by the Catholic Church. I decided to go there to understand what that felt like.

A step out of the comfort zone?

A step to look closer. The EU is something sacred, and wild things are happening right now. By producing art with queer content, I'm undermining narratives that right-wing politicians are putting out into the world, thereby contributing to visibility.

How did you approach this trip to Poland?

I didn't have a preconceived approach so as not to bring a narrative with me, I wanted to be open. In Poland, I met up with artists and acquaintances and tried to familiarise myself with the scene. I came across a queer rave scene that is super activist.

Your topic!

Exactly, that's where my work connects with what happened in Poland. It was about the queer club, not in a sexualised, but in a political form. There are key figures like the DJ collective Ciężki Brokat (Heavy Glitter) who are resistant and activist. They organised demonstrations during the PiS government and fought back tooth and nail. The club became a hub where everything came together. You can see it now in Tbilisi too: the techno movement is taking to the streets and fighting back. I'm fascinated by the power with which they show up.

A photo requires trust though. How did the people there react when you asked for their picture?

It's not easy to take photos in a club. The camera is often not wanted and being perceived as invasive. But the photos were all taken on location and in intimate settings, always with the consent of the portrayed people and the agreement of the club owners. That requires a lot of sensitivity, trust and dialogue. I came back again and again for over a year to establish contacts.

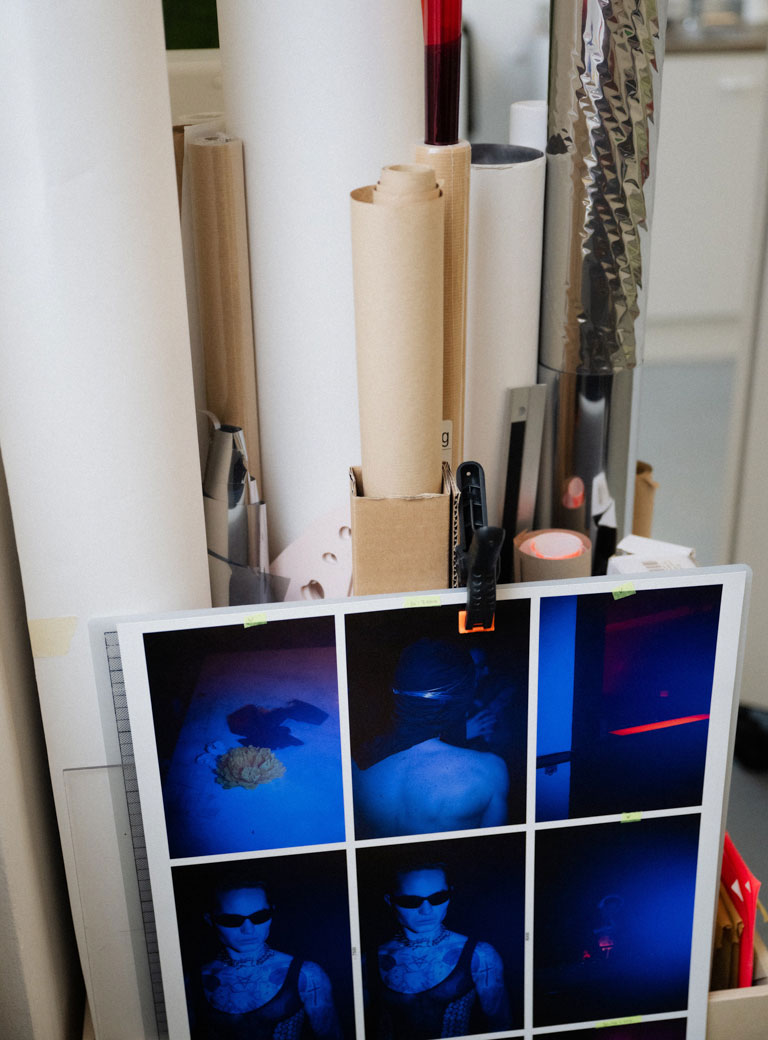

How did you take these pictures?

I realised that I needed a visual, non-invasive strategy. I don't want to destroy the club’s intimacy, it should remain in the picture. So I decided to use colour filters. That way I colour my work while I'm taking the photos. I choose a certain colour for each situation; I have all the filters in my trouser pocket. The flash has an attachment that bundles and focuses the light.

Why?

So that very intimate portraits can be created, instead of lighting up the whole room. It’s my technical setting that makes it possible. I use the camera like a spotlight, not to expose the people, but to illuminate them. The pictures are very sharp. Without the flash they would look completely different, very grainy.

It's probably easier to get to know people in the intimacy of a club - but how do you manage at big raves? Do you get to know the people you're portraying?

Yes, sure, it builds up over several ecnounters or conversations. Of course, some people might ask themselves: “What does he do? Does he have a camera?” But at a rave, people treat each other very sensitively, there's space and time to explain yourself. I'm definitely not a party photographer.

How easy is it to become part of the scene? When you go to a rave, do you join in, or do you stand aside as an artist?

I do dance too, of course! All night long (laughs).

And then you just switch from party participant to artist?

I always have my camera with me and remain professional. But I've always been a fan of electronic music. That's just part of it if you want to capture the scene in a credible way.

As far as the political situation in Poland is concerned, it has now eased, as PiS was voted out of office. What are you hearing from there now?

PiS is no longer in power, but my Polish friends tell me that those eight years have left traces and scars. Curators, for example, have lost their jobs and won't get them back right away. I also believe that the mindset of PiS voters has not changed. And the Catholic Church still has the same conservative and strong influence. All of this affects the rights of minorities.

You also travelled to Hungary, how is it different there?

The Hungarians have to put up much more resistance. Because Viktor Orbán has been in power for so long, there is less hope for change. That's why they perhaps lack the strength to demonstrate often or verbalise resistance in public. This makes the club all the more important. The scene as I got to know it is a bit tougher, or more hardened.

Was it more difficult to find people there who would allow you to take their picture?

Not more difficult, but sometimes I was told: “Yes, I'll give you my permission, but you can only show me from behind and you can't mention my surname”.

You found the scene in Warsaw and Budapest to be different: does your work reflect this?

Yes, there are fewer sunglasses in my pictures in Budapest because the people are more direct. But I only realised that later. And as a result, the Budapest photos perhaps seem a bit harder, because of the direct gaze into the camera.

Where will you travel next?

I am interested in Georgia, which is a focal point right now. I was shaken when I saw the images on the media. I've already thought about how I can get there. Access to the queer club scene is certainly more difficult because it's dangerous for the participants. It takes more time.

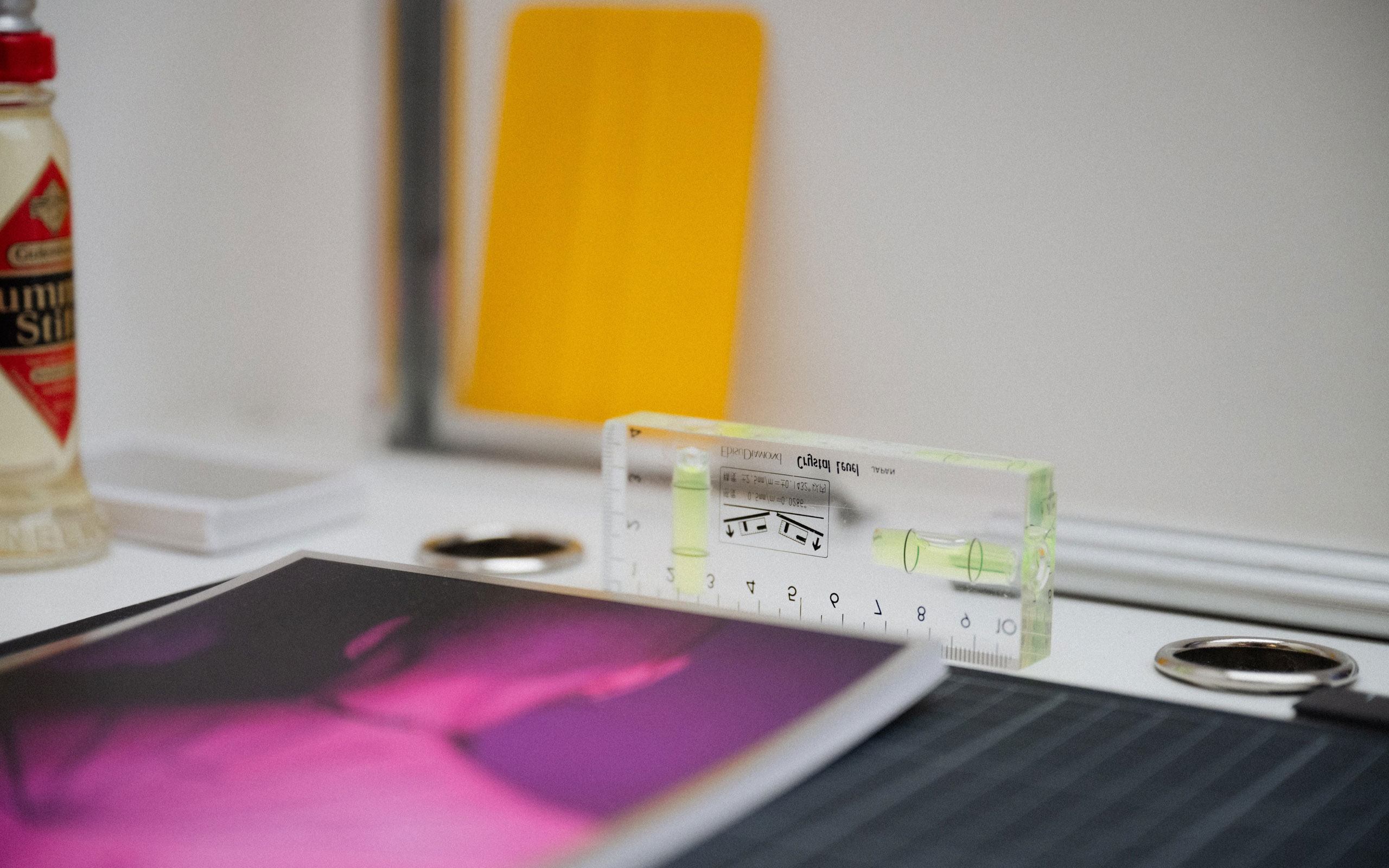

What is your experience of working in Vienna?

Vienna has a good structure for artists. For example, my studio is on the top floor of a municipal building. Because I'm travelling so much, it's a nice base for me. I have also received support from the BMKÖS: an artist residency in New York, the state grant for photography, etc. They take care of the artists here and there are good strategies to ensure that art doesn't just take place on the fringe.

Do you also go to raves in Vienna?

Not so much. Once a year I go to Hyper Reality, the festival for club culture. I know the scene in Vienna, but it doesn't have the same relevance for me as the one in Poland or Hungary. Because my work is about valorisation, about reversing a narrative.

So do you think the scene here is fine?

Of course not, Vienna's club culture also has its problems, such as assaults. But for me, this is not so relevant artistically at the moment, because I don't feel that we need to resist in an activist way here in Vienna. Not yet! I've travelled across the countries surrounding Austria, but when I look at the provinces around Vienna, I should perhaps consider going to Styria, which now has an FPÖ governor (weeps).

Mario Kiesenhofer's photographs from the Treasure series can currently be seen alongside works by Monica Bonvicini, Renate Bertlmann and Matthias Herrmann, among others, in the exhibition Cruising in the Park at PARK in Mondscheingasse 20 in Vienna.

Treasure, 2023, lettering made of anodized aluminum, chains, approx. 300 × 160 cm; Photographs from the series Treasure, 2023, pigment prints, mounted in chrome frames, each 40 × 60 cm

Exhibition view: Mario Kiesenhofer - Treasure, Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien, 2023/24, photo: Mario Kiesenhofer

Avtomat and Beata, from the series Treasure, 2023, pigment prints, mounted in chrome frames, each 40 × 60 cm

Exhibition view: Mario Kiesenhofer - Treasure, Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien, 2023/24, photo: Mario Kiesenhofer

Photographs from the series Treasure, 2023, pigment prints, mounted in chrome frames, each 40 × 60 cm

Exhibition view: Mario Kiesenhofer - Treasure, Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien, 2023/24, photo: Mario Kiesenhofer

Anna, from the series Treasure, 2023, pigment print, mounted in chrome frame, 40 × 60 cm; Reflections, 2022/23, 4K video installation (projected in full HD), jagged mirror, 450 × 254 × 204 cm

Exhibition view: Mario Kiesenhofer - Treasure, Bank Austria Kunstforum Wien, 2023/24, photo: Mario Kiesenhofer

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt

Links: