The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

Having worked in the Norwegian wilderness for years, Rune Guneriussen has experienced how gradual changes in that environment have impacted on his art. Being at the mercy of nature for the production of his art, his relationship with nature, has become more fragile than in the past, to the point where he no longer feels welcome in nature.

Rune, we live in quite exciting times to say the least. To what extent does this affect your work as an artist?

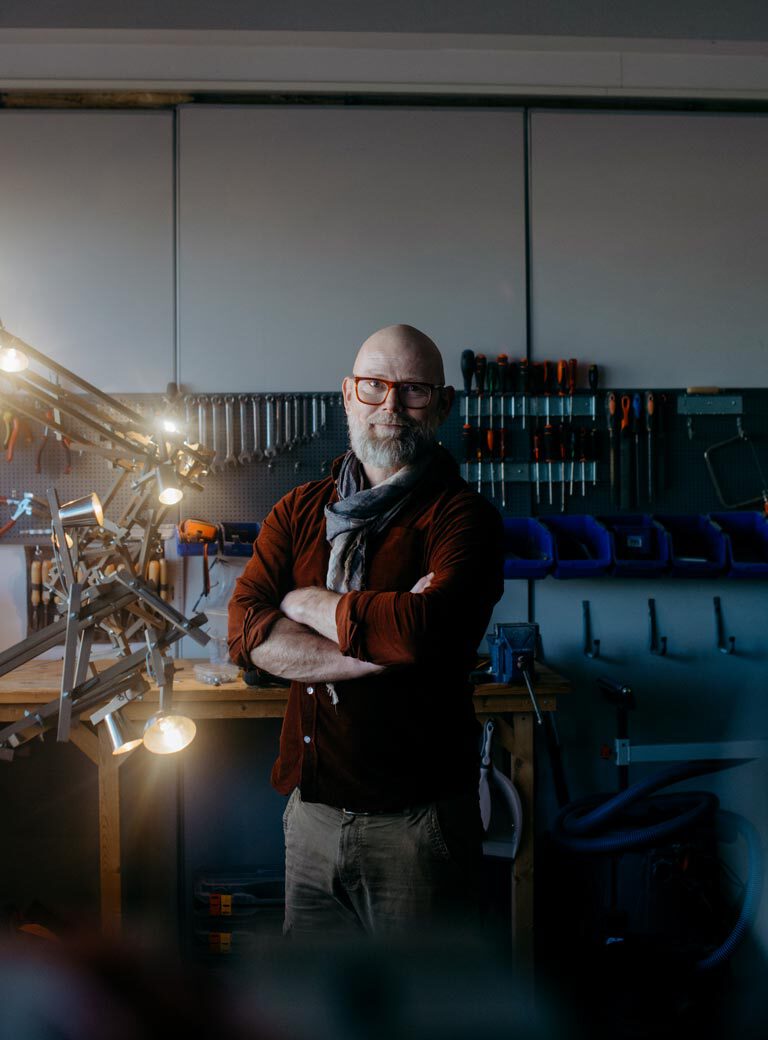

With the beginning of the war in Ukraine, I had to start thinking about what kind of work am I going to do now. As an artist, you have to adapt even though my relation to nature stays at the essence of my work. Maybe it’s me being more emotional or me getting older or maybe a better artist, but I want to stay close to what is happening right now. To have far-reaching plans, as I started out with; planning for ten years ahead, has become more difficult. Right now, I’m waiting for spring to come. The hunting season starts in April and lasts until October. For the next month, I’ll stay most of the time in my workshop building new sculptures that I will then take into the wilderness.

Nature is your playground. Can we see a change of expression in your work that has parallels with the changes in climate?

The pictures in Museum Kunst der Westküste for instance were done over the course of four years, so I think you can see a change. In my earlier projects, I was described as being poetic and romantic. In more recent years, I have become more dramatic, in the sense that it’s more realistic, in relation to the world outside myself. It’s no longer only about my intimate relation to nature, but more about deciphering the global relation to nature, and that makes it darker.

How do you experience the increasing darkness as you call it?

When I’m traveling in Norway, I see that something happening on a global scale is infecting small areas of nature, which I have revisited during the past 15 years. That nature is disappearing. It’s not about people cutting down trees, but something happening from the outside that changes it. You can feel the change from year to year, or sometimes over five years or so. When I arrive at the same spots, I don’t feel as welcome there as I did before.

Can you explain that feeling of being less welcome in nature?

When I find a good location it’s about connecting to it, feeling related to it, and nature accepting me being there. That is happening a lot less than before, which in turn influences my work.

What is your take on climate change at this moment?

What has been engaging me ever since I was young has been the crisis in which nature is destroyed. The crisis is still just as important to me but the approach has changed because we all have to come to an agreement in order to solve the issues. It’s possible to make a change since we have technical development.

The eradication of nature is something that in turn is impossible to reverse. My work is about getting back to the relationship with nature.

Conclusive vastness to pass (2017), Digital c-print/aluminium/laminate, 150 × 247 cm, Courtesy the artist

Fiery wingless and into growing regard, 2020, Digital c-print/aluminium/laquer, 120 × 170 cm, Courtesy the artist

Roots of kinship, 2019, Courtesy of the artist

What does working mainly in Norway mean to you?

I have forests and nature in every direction. It wouldn’t make sense to travel far away to make art when my work is about conserving nature. The crazy thing is that I’ve never, in 20 years as an artist, been to the extremely popular Lofoten area in the north. I couldn’t really justify driving 2.000 kilometers to make a picture of nature. But then again, I’ve experienced guilt trips in going to the Alps for a public installation.

So you are always trying to leave as few traces in nature as possible.

Yes. Moreover, when I find a good location I spend two to three days working on the same installation. I walk around causing as little disturbance as possible to take my picture, and I don’t leave anything behind. The surroundings look exactly the same when I’ve finished.

Your installations in the middle of nature are stunningly elaborate. How do you actually make them – for instance, the tower of books on the beach that you created for Basic Object Oriented Knowledge Systems (2009)?

First, I’m always looking for locations whenever I’m traveling. But it usually takes me several years to actually go there to work because I have to plan for it. Second, the amount of material it takes to build something means I have to plan it rigorously. In terms of the books, and many of my other works too, the work becomes very physical because of the weight of the books. For the first tower of books, I found a location by the sea in the western part of Norway. The distance between the location and where I had to leave the car was two kilometers. I had to walk the distance back and forth twenty times carrying the materials, just for that single installation.

What does this tedious process mean to you?

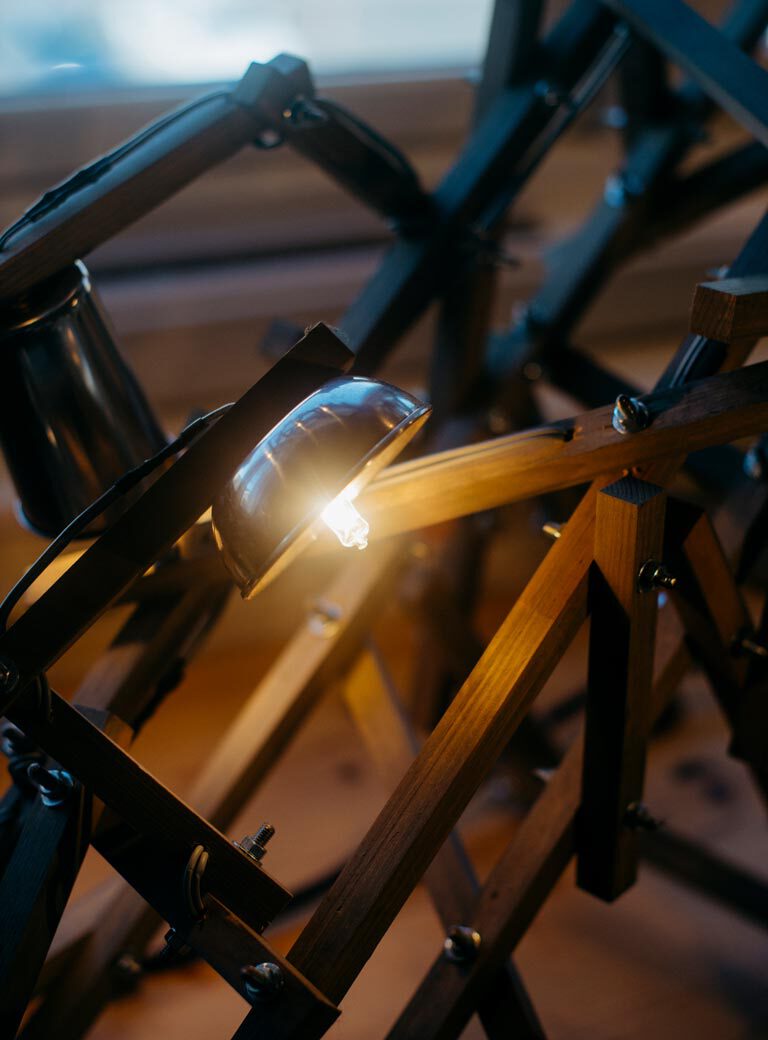

I love the physical work. But it also means that every time I walk away from the installation and back, I do some adjustments. With this repetition, comparable to a painter throwing paint over a painting, again and again, my work becomes better with each small adjustment. In this picture, you can see a small opening for the light to come through. That was planned three days in advance because I had to do this walk. Small details like this are what make something magical. I’ve tried to make things faster, too, as I’m getting older and don’t have the same amount of patience. But it’s the duration of time that actually makes for a good piece of work.

Is it always just you setting the installations up?

All of the installations are seen only by me, with the photograph as the only evidence. It happens people out for a walk in the woods suddenly see me climbing a tree, building something, with the lights on and all the equipment around, I imagine for them it may be a little overwhelming.

Do you have a project that has been especially meaningful to you?

The title piece of an earlier project called A parasitic gesture (2011) came about during a period of nine days. I found the location while fishing; a tree that was so beautiful. I waited for a couple of winters when there was ice on the water so I could transport equipment on a sleigh. People might say the picture is beautiful. But what happened midway while setting up the lights was a realization of how scary it in fact was. When I looked at the installation from afar it was quite small, set in a huge landscape. It looked horrific because it was something that shouldn’t be there. When you’re up close, it is intimate but in a landscape it becomes scarier. As the title suggests, it is a parasitic gesture towards nature. If you look at Europe from above you will see the exact same. This experience intensified my own respect for nature.

You have expressed your dislike of art dictating the way of how to understand it. What kind of approach do you prefer?

In the same way that the artists and their objectives are secondary to me when I look at art, I don’t want my art to be direct either. It’s about how the objects are playing with nature, telling a different story each time, but only as an indication of something. You should let your mind do its own walk through nature, through your mind, and through the artwork. Only then will you come up with something for yourself. Art shouldn’t hit you in the face. That’s dictatorship.

The installations depicted in your latest collection of photographs consist of different objects that you are known for using, being more enigmatic and up for wider interpretation. What changes do you sense in your work?

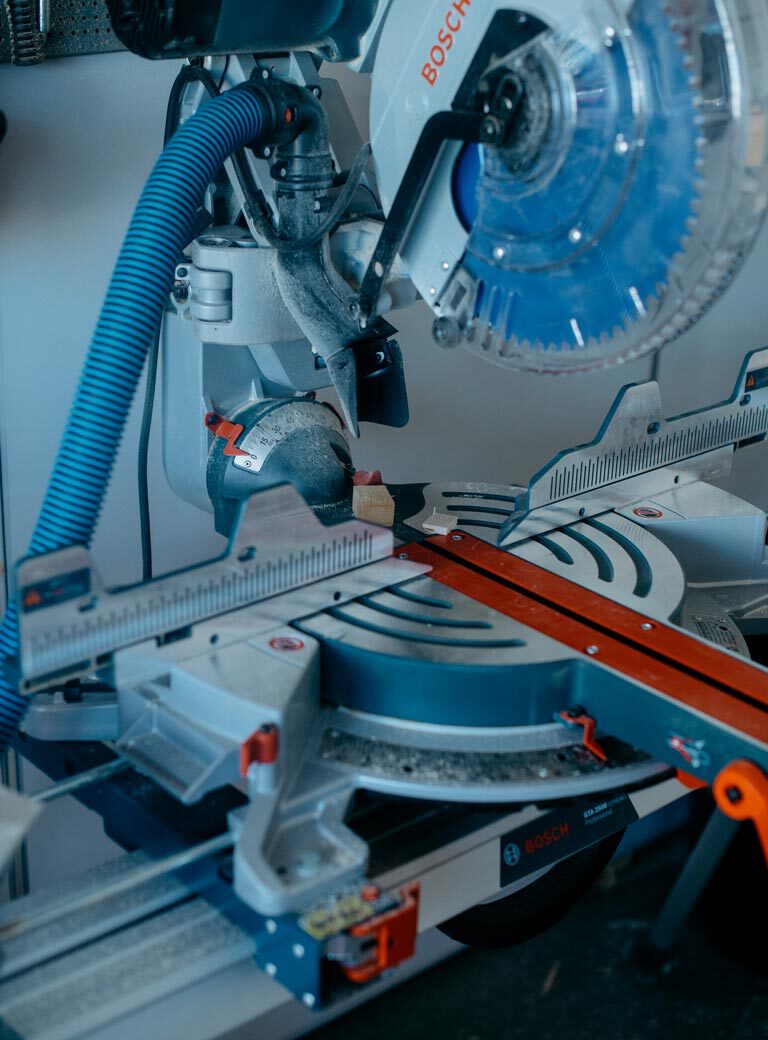

Before, I was taking something that people had thrown away, like lamps, books or something that I could buy at flea markets. For Lights go out (2022), I made all the objects myself from scratch. This required me to be in the studio building the sculptures for up to five weeks. These works are based on my own perspective and my inspiration from the world, while using the discarded objects was taking a memory of something and bringing it into the art.

These new objects are more puzzling, take for example the strange, presumedly living, creatures in Fiery wingless and into growing regard (2020). Is this new kind of elusiveness something you strive to cultivate?

Some of the objects are concrete as well but you need that duality of the concrete and the abstract because that’s the way our minds think. We have to have something to connect to, a ‘hook’ to hang on. I can find beautiful nature wherever I go, but I still need that single thing – the hook – that a tree, a branch or a little piece of green can give me in order for me to introduce the abstract aspect.

The exhibition at Museum Kunst der Westküste has been titled Lights Go Out. Can I sense a pun or two there?

Working with titles is a story of its own. When I created my first titles I was fresh out of school and they were bad. Later on, I have put a lot of effort into the titles, and this process has become quite fun. This title is my way of looking at the world: when ‘the lights go out’, it has an optimistic ring to it because the lights are still going out. But it’s also about lights actually going out on us, as they have done for a long time now.

At no time defeat sunrise (2014), Digital c-print/aluminium/laminate, 150 × 211 cm, Courtesy the artist

A parasitic gesture», 2011, 207cm x 150cm, Courtesy the artist

Basic Object Oriented Knowledge Systems, 2009, Courtesy the artist

Interview: Rasmus Kyllönen

Photos: Signe Fuglesteg Luksengard