A layman scientist in an artist’s body is a way to describe Dutch photographer Sjoerd Knibbeler. In his exploration of nature, he has looked up to the moon and back again – lately finding awe in the nature of the German island of Föhr. By employing technology, he comes closer to the non-visible world.

Sjoerd, one description of you states that you are on a ‘scientific quest’. What does this mean?

Actually, it would be more accurate to say that I’m on an artistic quest. But I’m very interested in the world of science. To me there are many similarities; scientists and artists are often looking for the same thing – dare I say it – truths. So I’m interested in the scientific world that is searching for laws in nature. Photography, the medium I work with, is also governed by those same laws of physics. I like to question them, but in a slightly different way than the way scientists question themselves. At the heart of it all is this notion of what it is to be human. Why do we have science and art in the first place? How did that come about? How did we invent that? This is endlessly fascinating to me.

I recently bought a book about how science actually was ‘invented’ – and in the history of mankind it’s fairly recent actually. We’re seeing the fruits of that labor as we speak.

And at the same time, there are some quite rotten apples among those fruits. The human desire to discover the world leads to all of these varied kinds of ideas and technologies that can also sometimes be devastating.

What do you mean in particular?

For instance, with Paper Planes, I made a series of photographs of origami models of aircraft. They were all modelled after military airplanes that never made it past the drawing board. These were machines designed for warfare. On the other side, there is this dream to be able to fly, which is a very innate human desire that probably most of us will recognize. Lunacy touches upon the desire to venture out into space and discover the moon, which has been a fantastic source of inspiration for many writers and artists. At the same time, the actual engineering is mostly done by the military.

Does your fascination with science have an origin?

In my childhood, my dad used to take me birdwatching every weekend. He was a bit of an amateur biologist, so for example we would go out with a net to a pond and see what kind of aquatic life we could find. I was the kid with the binoculars. I think this is where my interest in the observation of nature started. When you have so much knowledge at your fingertips just going on the Internet, I feel that you kind of lose this experiential knowledge of actually doing stuff yourself. Because after all, can you discover the world through media? There’s something profoundly different about discovering the world yourself. That’s why I always think I have to do it myself, albeit not always knowing how to go about it.

I-Ae-37, Paper Planes series (2015)

Annex, Lunacy series (2017)

How do you go on with exploration and discovery?

I don’t define strict research questions regarding the actual work. I’m curious by nature and I want to get the best information possible, and usually explicitly first-hand knowledge. Whenever I’m interested in a topic, I try to reach people and have a chat. This informs the work. It’s about finding a connection with this scientific world. Subsequently, art is then a laboratory where I can test out ideas. It allows me to dream and think beyond.

How would you describe your relationship to the nature around you?

My work takes its inspiration from nature, but it’s essentially about what we humans do in nature. I’m not looking analytically at nature as a scientist. But I do look analytically at what scientists look at in nature. It’s not about nature as such, but about our desire to be either part of it or to distance ourselves from it. And the effect that we have on our natural environment.

What thoughts on nature would you wish the viewer to gain from your works?

I don’t want to steer thoughts in any direction, but it would be great if the work somehow invites people to take another look at their environment and raise questions of how things are done. To sort of trigger epistemic emotions like curiosity and wonder. If I can instill even a tiny fraction of that into the viewer I’m already very happy.

In your work you venture outdoors. How was the exploration with shooting in moonlight for the Lunacy series?

It was the very first time I went out into the field at night. I had built two sets that I wanted to photograph. I knew that I had to create a stage for this model to be on the moon, so to speak. Because of the size of the model I had to create a stage which was six by six meters, and it had to be slightly slanted so that it would look up at the sky. But I had to create this all from scratch in this field. There was some serious set building going on. It was a bit damp so everything got quite wet as the night evolved, including my camera. I think we were working for 10 to 15 hours. From that very first night I managed to do one good shot. This is what usually happens: I go on and do something only to find out all the mistakes I’ve been making and then slowly progress from there by trial and error.

In your own way, you did some sort of a scientific experiment – and it paid off. The photographs shot in the moonlight are otherworldly. Can you even recreate a light like that?

I’ve tried to synthesize it in the studio, but I failed. The light is so soft. During the two first months we went out in the field, of course, you can only go once a month, I figured out that I need exposure times of about 30 minutes. As the position of the moon is changing in the sky, the shadows are slightly moving. So there are all kinds of things that later, when you see the pictures, make total sense. Beforehand though, I can’t think of it. I just have to do it.

You have spent time on the island of Föhr in northern Germany, home to Museum Kunst der Westküste. What did this place become for you?

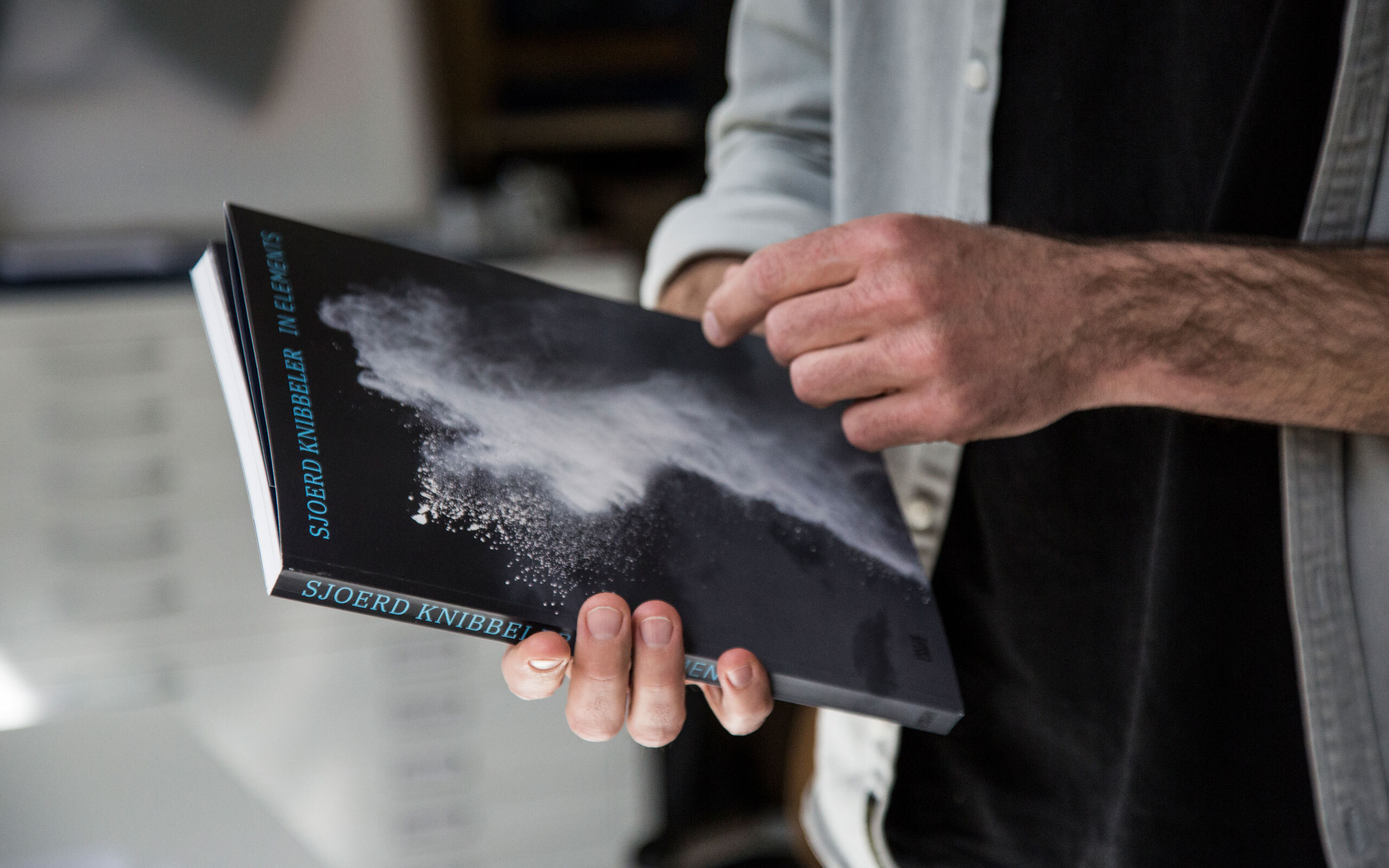

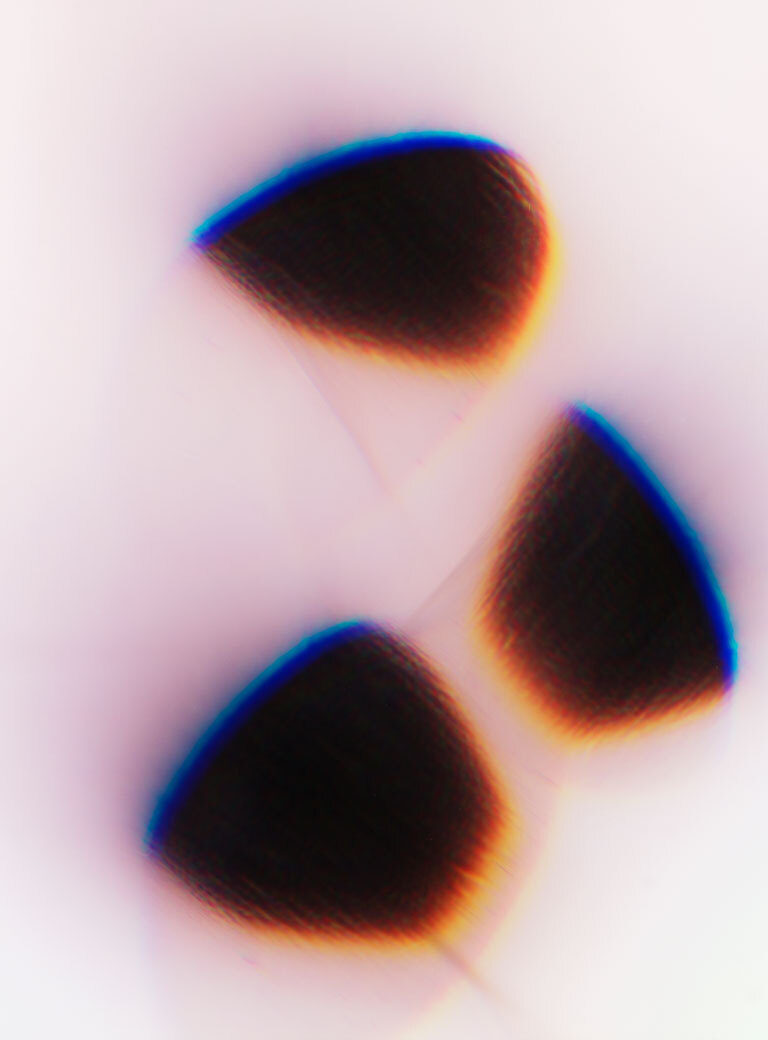

It’s a very beautiful place with a climate that can change between seasons in the course of a day. The curator of the museum’s residency program had seen my work on the wind and thought it would be interesting for me to work on the island. I went there for the first time in 2017 and went back twice over the years. During these residency periods I developed two bodies of work. The Exploded Views, for which I refracted sunlight with prisms in self-made camera obscura. The latest series titled In Elements, I shot on the beaches, wetlands, and the sea surrounding the island.

You switch between working in the studio and outside. How is it working outdoors?

Honestly, I have a love-hate relationship with it. With the latest series that I shot on Föhr, it gave me many interesting accidents that were very useful. But also, especially with Lunacy, my window of opportunity was very – very – narrow. What happened was, that I set up everything for a shoot, but then a fog made me wait another month. When it does work though, it’s magical. The studio is where it starts; it’s where I can test things on a small scale. But doing the shootings outside reminds me again and again how much it contributes to the work, despite me cursing when I’m out there. I’ve also realized, I should be more present. Being busy with construction makes me forget to appreciate the moment.

What were these accidents on the island?

In a similar way as with Lunacy, I had not yet settled on the technique when arriving on Föhr. I was still thinking about how to disperse the chalk I was going to use into the sky, so I brought a lot of different structures with me. I had a plan of creating some sort of a wind-powered machine. What happens quite often in my work is that I do too much, before breaking it down and realizing what’s just surplus. Thus, with In Elements, I went from trying to build all these machines to just using a pipe. Then I thought I needed perfect weather conditions, because I had this picture in my head. Obviously, it never works like that. When I settled on the technique of the pipe shooting calcium carbonate up in the air, me and my assistant went every morning, afternoon, and evening to different parts of the island to repeat the experiment. What we had in the end were less favorable conditions, which actually added to the photographs.

Why the chalk?

It’s the same material that is being researched to be dispersed in the stratosphere as a form of geo-engineering. It’s a very radical idea; alternating the Earth’s climate artificially by blocking the sun. Now – for humans that’s not even that radical in itself because we always change the world around us.

You are humbly under the influence of weather and nature. What part does the camera then play in your work – is it a more stable factor?

It’s always been at the heart of my interests – I have in fact even built some myself. First and foremost, I see it as a tool for my experiments. A tool I control and adapt to my needs, in contrast to the subjects I’m trying to capture with it.

Does the role of the camera change?

There is always a specific role for the camera in the equation of the experiment, which is to document, but I use this quality in different ways. I use the camera quite plainly to solely capture the moment. I don’t do much post-production either, but instead focus on pre-production before the actual recording. I alter the photograph before it is made. In that sense, I’m not a typical photographer with a certain way of working: I invent the method with whatever it is that I’m working on.

Earlier you said that the camera is revealing processes that wouldn’t be noticed otherwise. Can you elaborate on that?

By its very nature, the camera is able to actually freeze these moments barely visible to the naked human eye. This is connected to the In elements work where you have this short burst before it’s gone. On the other hand, the camera is able to compress time into a single image, which is the case in Lunacy. I’m also interested in how the camera proposes that there’s always something in front of the lens – otherwise, there wouldn’t be a photograph. But what if that subject isn’t able to be in front of the lens because it’s in the past, or even the future or so far away that I wouldn’t be able to get my lens in front of it. The topics that I’m interested in photographing are the ones that I’m not able to, like the moon landing. I want to get close to that moment. Or take the wind for instance. We can only feel it, so how do you actually make it visible in a photograph?

Technology has been popping up as a keyword in this interview. How is it enabling us to discover the world?

First, my artistry is technical in nature, because it is photography-based, so there’s always the machine that is part of the creation. Second, technology is part of human nature. I think our only way of discovering the world is through creating technology. By this I mean technology in a broader sense, not only computers. The distinction between nature and culture is not as strict as we like to think.

In Elements (SE-NE) (2021)

Exploded View # 75 (2017)

'Vortex', courtesy of Collection De Groen, installation view, Museum Kunst der Westküste, Germany (Photo: Sjoerd Knibbeler)

Interview: Rasmus Kyllönen

Photos: Silvia Martes