Bernhard Cella approaches his work in a methodical fashion, through which he develops his artistic practice within a coordinate system. This way, he considers both the role of authorship and the cooperation with partners who participate in the realization of his works. The result of his work, be it the Salon für Kunstbuch (salon for art books), a video installation or an art project, is generated through a participatory process. Cella is not only concerned with the involvement of the general public, but even more with emphasizing art as a social process. It is about addressing the aspiration for publicity itself and putting it up for discussion.

Bernhard, we are in your studio, where thousands of books are placed on shelves and displays and stacked on tables. This immediately makes me think of your Salon für Kunstbuch (salon for art books): a project where you transformed your artist’s studio into a model of a bookstore. What was the thought behind it?

In 2007 I converted my former studio in Mondscheingasse in Vienna into a life-size model of a bookstore, the Salon für Kunstbuch (salon for art books). The decision to work in this way came from my perception of the Viennese art public at the time. Contrary to many of my colleagues, I had no desire follow the traditional production and role pattern as an artist. Therefore, my studio became a mix between a stage and a laboratory, including a street entrance and displays, where the boundaries between private and public space blurred.

What did you show there?

Over the course of several years, I have gathered what artists, theorists and authors have developed, which also includes the forms in which they express themselves in the medium of books. From these material aspects there were sculptural processes to be derived. It was a growing collection of publications that are rarely seen – artist’s books, theory and literature books, combined with striking, shapely, often minimalist graphic design. There, the book could be seen in a new way as the intersection between an exhibition object and an article of daily use. There was, for example, out-of-print literature from Mexico, recompiled by hand, but also standard works found in every library. The materials were not precious; instead, there were book covers made of fabric and individually brushed with oxblood, books that resembled large-format glossy magazines, with photographed flower bed motifs, or facsimiles in which only the handwriting could be deciphered.

Could these art books be purchased?

Yes, these books were for sale, otherwise the function of the room would have been a different one and you would not have found yourself in the model of a bookstore, but only in a library. This salon took up a conceptual practice that can be found in the American art of the 1970s, such as Sol LeWitt’s.

On the one hand, the focus of your project was on society, the public, and on the other hand, there was the medium book. What happened between the two?

There was indeed a strong social moment. The project had partly aimed at initiating and enabling specific forms of communication that would not have been possible otherwise. The installation acted as a catalyst for interactions and forms of communication through art. The books, in turn, were important for setting this process in motion; they charged the installation, so to speak.

So it was some kind of laboratory situation?

Yes, I was able to investigate topics that were of interest to me within my changed work situation. With the on-site installation, it was possible to do two different things: it worked as expected and was at the same time the model of itself.

Who came to check out your salon?

Initially, there were only a few people, but later, when the subject “book” had caught up with the Viennese art scene, around 2011, more and more came. Some even came to introduce me to their own publications. I found this interesting, because since the beginning of the salon project, I had been faced with the question of how a visual artist can get involved in the art discourse today without losing eye level, i.e. without too much loss of control over one’s own work and the implementation of one’s own ideas.

How did you deal with the fact that some people thought you were a bookseller?

Well, there are still people today who will say: “I’ll come to your shop” (laughs).

Does this annoy you?

Not really. I often work with misunderstanding as a kind of catalyst in my work: it is not a stumbling block for me, but more of a means to an end. If you create a misunderstanding, it leads to irritation and thus to a thought process. People need to think about what it is all about. It is always the stumbling blocks that lead you to something.

You’ve since moved to another studio, but it also resembles a bookstore somehow…

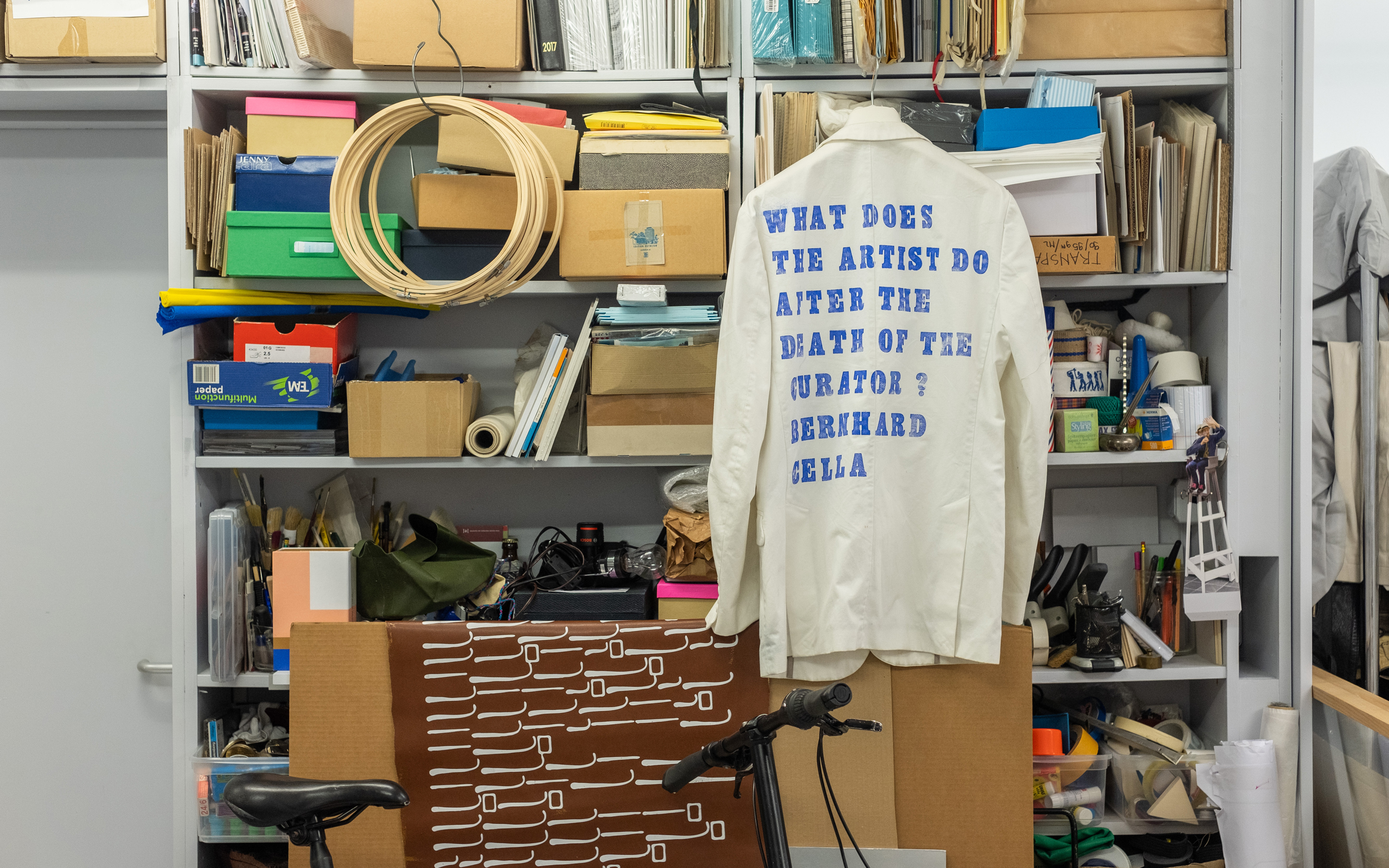

One third of my new studio is taken up by the archive of publications that I have collected since 2007, the other two thirds are production rooms. For me both the analogue and digital archives are always a lively place where I like to spend time, and which are often the starting point for new works.

Do books and visual arts have the same meaning in your projects?

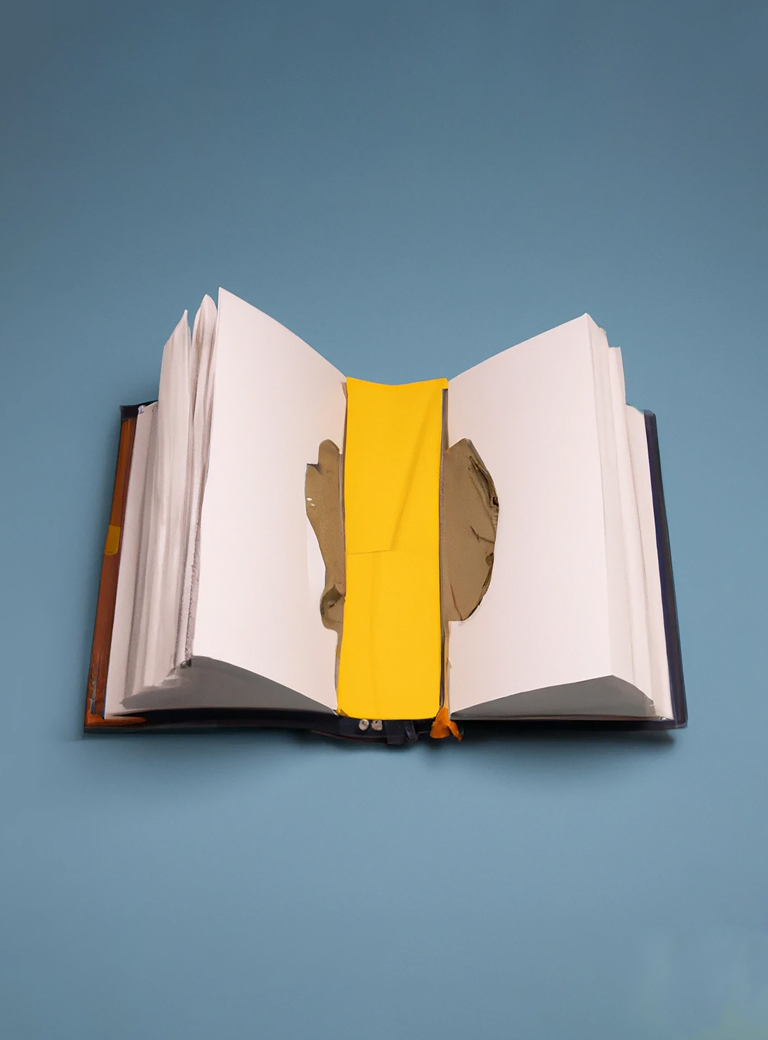

I am fascinated by the idea of an interaction between books and visual arts. For me, the book is a logical consequence of conceptual art. When I develop a work that is space-related or performative, it will disappear after. And the question is: how do I deal with what is left of my work in terms of documentation? How can I transform my concept into something that makes it visible? That was the starting point for me to concern myself with books. The idea of publishing is my logical conclusion, because books are also spaces for me.

The Salon für Kunstbuch (salon for art books) was also put up as an installation at the Museum Belvedere 21 for some time?

When the then director Agnes Husslein opened the 21er Haus, she approached me with the offer to develop my own implementation of this salon. My proposal for such a site-specific installation was eventually purchased by the Belvedere and I became the curator of my own work. It was a real fitness training, a museum endurance run in an institution, which put me in the unusual situation of being employed by the museum to develop my own work! For 8 years, this was unique in the world, and happening only in Vienna. (laughs)

So do you also see yourself as a curator?

Well, at the end of the day, probably no one cares whether you do what you need to do as an artist, curator or publisher. It is simply a question of whether what is being negotiated here is of interest. Besides, as an artist, you are curating all the time anyway.

How did you get into books?

During my studies, I developed a relatively large number of works that were only temporary and process oriented. Ultimately, this confrontation initiated my interest in the medium. I also found this moment very attractive, of books being unobserved and underestimated in the art world.

I have the impression that the book is at the top of your list as a medium of transmission. Are visual arts or literature less important to you in this respect?

No, I have no idea of hierarchy at all. But I was interested in books because their impact had been underestimated.

In your studio, you still sort books by color, as you did in the Salon für Kunstbuch…

In my studio today, I experiment with publications and try to develop new works. So color-sorting can obviously happen. Initially, this aroused a big response. I was asked again and again if I was the one “with the colors”… As an artist, you are always a designer.

Unfortunately, some books were stolen in your salon. How irritating was that?

The unexpected theft of many publications from my studio in 2010 made me almost put an end to my 1:1 model, as it seemed unfeasible. Without my counter-intervention of the Manquants (French for “the missing”), I would probably have ended the process, but they became a memoir of perseverance – by pulling through in the face of an unforeseen problem. Ironically, mainly well-known titles in art theory or critical of the system such as Did Someone Say Participate?: An Atlas of Spatial Practice, Art and Subjecthood, The Return of the Human Figure in Semiocapitalism, Situationists and others and Manifestos had been stolen.

You were saying that this was how the Manquants series came about?

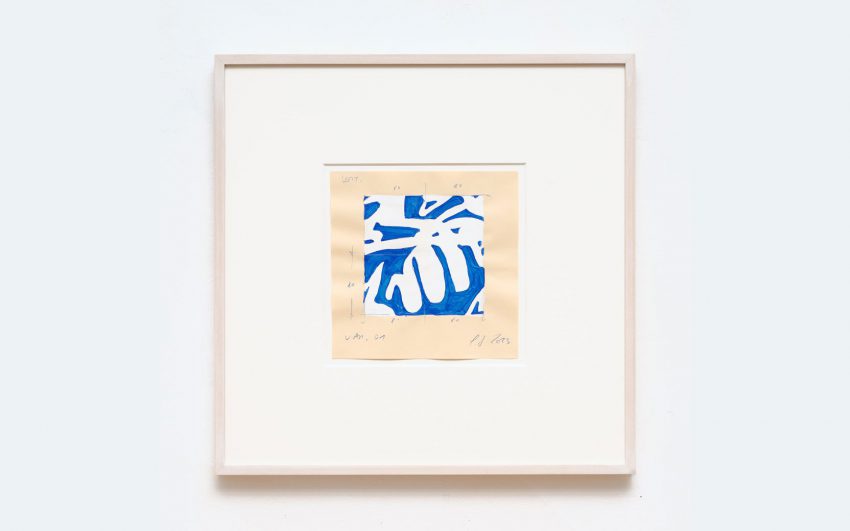

Yes. The Manquants arose from the series of publications that had been stolen from my studio. Among them were many titles that I was not able to buy again. The series of Manquants was created between 2012 and 2014 and includes a total of 58 different tapestries in the format from 30 x 40 cm to 48 x 60 cm, which I weaved using the jacquard technique.

As a kind of antithesis to the traditional technique of jacquard weaving, do you also work with AI?

You are referring to a work that I developed together with the artist Seth Weiner and from which a publication emerged. I would say that I am experimenting with this new technology, also in interaction with colleagues. The work you mentioned is titled Handmade and is an ecstatic archive of synthetically produced artist’s books. Using a combination of AI images and descriptions, the book not only records a series of material proposals, but also a visual discussion between Seth and myself.

Does this mean that, in this work, you show depictions of books that don’t even exist?

We show depictions of publications that have been constructed entirely from text-generated images. They are pictures of possible real books. We were interested in what “Handmades” are or what they mean. Everything that is made by hand does represent the artist who, according to our thinking, still does everything himself, from the first thought to the execution. But this does not agree with the time we live in anymore.

Is AI eliminating the artist?

Why should a machine that can combine but that cannot think creatively replace us? From my point of view, we live in very exciting times. We have to ask ourselves what a creative act is, what knowledge is. To what extent does something new actually emerge and where do I want to go with it? Isn’t it quite extraordinary that using such a technique, I can express and try out myself?

Do you want to do that through your own art as well?

Of course! I produce art in order to clarify certain things for myself. I am looking for answers. My work is nothing more than a visualization of this process. Therefore, I would say that art is always a process of realization. Because: if I have found a style now, do I reproduce it for the next 30 years, or do I ask myself certain questions and develop myself further? And this development often leads to unexpected paths.

Such a path also led you to the research project NO-ISBN. What was that all about?

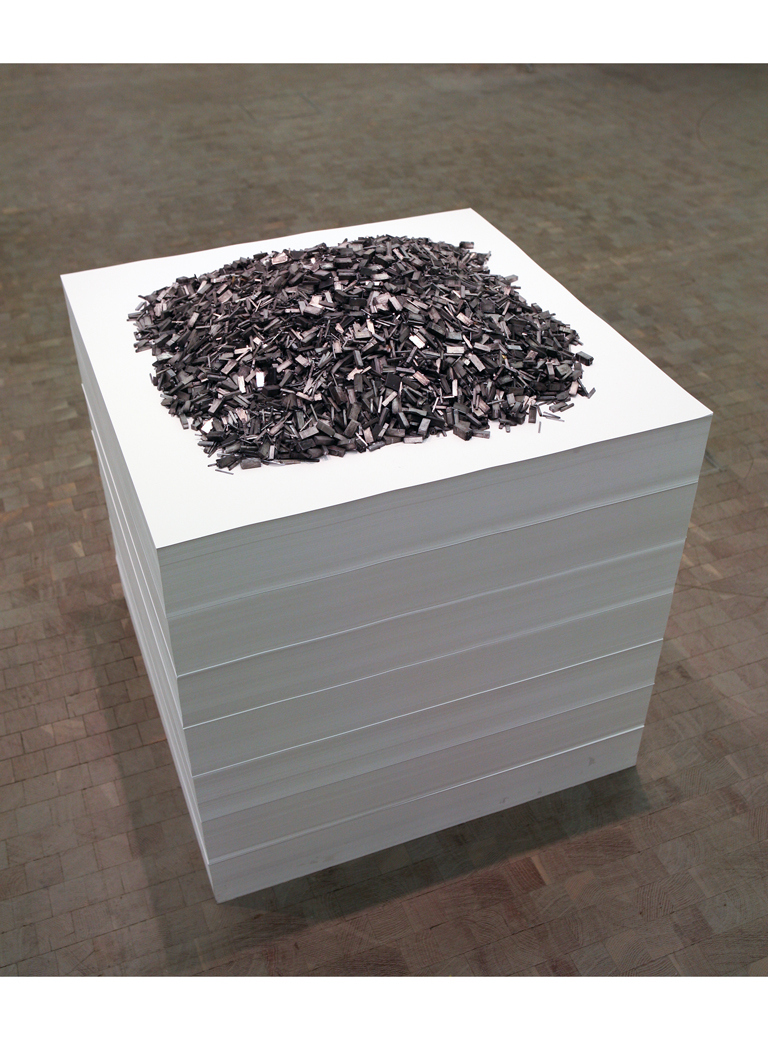

NO-ISBN was first created as a performance that I presented at the MOMA/PS1 in New York in 2009. It led to reactions in the form of printed works of all kinds, which I subsequently received by post. These became part of a collection that was the starting point for a research project within the framework of the Austrian Science Fund FWF. As an artist, the publications themselves also serve as material and starting point for me to develop works and explore new questions.

Do you think that the importance of books in the digital world will be preserved?

A book is still the best storage space, there is no other medium that I can open and read from after 400 years. I recently handled a book from the 16th century: it is amazing, the colors weren’t even yellowed, even though it is 400 years old. I believe that the book is still the best backup medium ever. Books are closer to timelessness. Digital photos, for example, have to be constantly transferred to new hard drives because you don’t know when they will give out. The safeguarding of my work is to make a publication about it.

What is the common thread that runs through your work?

This I leave to others to judge, but in short, my work is almost always about developing a structure that allows me to trace an aesthetics of the social. For this way of working, I often choose motifs and methods that are inherently aimed at the general public.

Back to analog, Bernhard Cella, 2006

NO ISBN, Bernhard Cella

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Maximilian Pramatarov

Links: