Italian artist Davide Allieri works with sculptural and installation-based forms that explore what remains once human function has disappeared. Drawing on technical and architectural vocabularies, his practice examines states of abandonment, suspension, and post-human temporality. Influenced by science fiction, cinema, and critical theory, Allieri creates environments that feel both familiar and subtly displaced. Through materials such as fiberglass, he produces hollow, resilient structures that function as containers of memory and potential, inviting reflection on time, technology, and the contemporary condition – a future that already feels present.

Davide, when did you first know that you wanted to be an artist?

Very early, I think. Already in primary school. During breaks, I was always drawing on the floor and on the walls, while the other kids were playing football.

So art was present from the very beginning?

Yes, always. My parents sent me to a private Catholic school, run by nuns, very strict, very traditional. But even there, the teachers noticed that I was really into art. And also at home, it never really stopped. When my parents were working, my brother and I stayed with our grandmother. In the afternoon, she would sleep, and I would use that time to draw. I would move the furniture a bit away from the walls and draw behind it, using the edges as a guide so that no one could see it. Only when we moved out of that apartment, everything came out. The walls were completely covered in drawings, in the living room, in my bedroom, everywhere. They had to repaint the whole place. (laughs)

And did your parents support your decision once you really decided to become an artist?

Absolutely. They were never worried, not at all. Actually, it was the opposite. Both my parents work in a bank and despise their jobs. They spent their whole lives doing a job they did not like, and they were very clear with me about that. They always said: Do what you want. Don’t spend your life doing something you hate. So in that sense, I was very lucky.

What were your first concrete steps as an artist? Where did you study?

In Italy, we have art schools already at the high school level. So, when I was about fourteen, I attended an art high school, which we call a liceo artistico. From that moment on, my education was always focused on art. After finishing high school, I moved to Milan and studied at the Accademia di Brera, the Academy of Fine Arts. That was in my late teens and early twenties. So it was a very continuous path; there was never really a moment when I stopped or changed direction.

How would you describe your artistic concerns in your own words? What matters most to you within your practice?

Let me try to explain it simply. I’ve been thinking a lot about forms, technical and architectural forms, and what happens to them once their original human use disappears. I’m interested in what remains when function is gone. My work often focuses on shells, containers, and suspended devices. These are forms that exist in a condition of abandonment or inoperability. They are not broken, but they no longer function. For me, they exist in a kind of post-future temporality.

Are there any contemporary artists who have influenced you and your work?

Yes. Matthew Barney, Philippe Parreno, and Pierre Huyghe. Adrián Villar Rojas, as well. His work has been very important for me.

Science fiction seems to play an important role in your work. Where does that interest come from?

Science fiction has always been important to me, especially the idea of dystopian environments. But I’m not really interested in catastrophe or apocalypse as a spectacle. That way of thinking became more complex for me after the COVID pandemic. I come from Bergamo, which was one of the places most affected during the pandemic. A lot of people died, and the experience was very real, very close. In that sense, you could say that something like an apocalypse entered my life directly. That definitely influenced my work. But it wasn’t the beginning of these ideas. Even before that, I was already working with concepts like voids, absence, abandonment, and post-human existence.

Your work is often read as dystopian. Is that a label you identify with?

I wouldn’t say that my work depicts a dystopian scenario. For me, it’s more about showing a state where form survives its subject. The human presence is gone, but the structure remains, silent, waiting for something that will never arrive. What interests me now is the idea of objects or devices that are not ruins, not broken remains, but something else. They feel like they are waiting. They exist in a kind of limbo, an in-between time. It’s not after something, nor is it before something else. It’s right in the middle.

The works also feel like remnants of an unknown time. How do you think about temporality within your practice?

I often look for references to think through these questions… and Marc Augé’s idea of non-places is especially important to me. It’s very close to how I understand time. For me, time isn’t circular; it’s more like a stretched line, an extension of the present without a clear past or future. When you enter a space shaped by this sense of no-time and no-place, it creates a certain tension, a threshold. You’re not fully inside, but not outside either. That’s why I don’t see my work as dystopian in a classical sense. I’m not interested in ruins or familiar dystopian clichés. These spaces feel closer to a parallel reality, almost like a simulacrum, something recognizable, yet slightly off.

Are there any artists, writers, or thinkers who have strongly influenced your approach?

First of all, cinema. Film has been a huge influence for me, especially science fiction, but also directors like David Lynch and David Cronenberg. And Michelangelo Antonioni as well. Antonioni is very important to me because of how he worked with time. His films have this idea of extended time, almost no time, very slow, very flat situations. Of course, his work was connected to a specific political moment in Italy, but what interests me most is his use of landscape and image, the way space and atmosphere carry meaning. I’m also a big film collector, including Japanese anime like Ghost in the Shell, Evangelion, and Akira. Those worlds were very formative for me. In terms of writers and thinkers, Mark Fisher is very important, as well as Timothy Morton, Nick Land, Giorgio Agamben, Paul Virilio, Marc Augé, and Baudrillard. And there is also Franco “Bifo” Berardi, who is not so well known outside Italy, but for me, he is extremely important.

What connects these different references for you? Is there a common thread?

Yes, definitely. They are all connected by a shared way of looking at the present and the future. And they are all, in different ways, critical of capitalism. For me, capitalism is really at the core of the situation we are living in now. We are in a moment with very little sense of the future and very little perspective. The big utopian ideas of the last century have collapsed, and what remains is a kind of flat line; everything feels stuck. Maybe this feeling is also very Italian. Italy often feels like a country without a future. Many people leave, no one really knows what to do next. This condition is deeply connected to the capitalist system.

You’ve said before that your work is not simply dystopian. What does the term “dystopia” mean to you in relation to your practice?

For me, dystopia is not really about a distant future. It’s much closer. It’s almost the present. It’s about where we already are, and about the possible evolution, or non-evolution, of what we are living through now.

So would you say that we are already living in a dystopian present?

Yes, exactly. “The future is already cancelled,” as Mark Fisher would say. Of course, I don’t mean that there is literally no future. But in a way, we are already living in it; the present itself feels like the future. Everything is changing extremely fast. Artificial intelligence is entering almost every system – work, production, and communication – along with drones, robots, and automated processes. Maybe this speed is exactly the problem of our time. It creates a sense of no perspective. Or maybe it feels like there is no future because we are already inside it. Everything happens immediately. There’s a metaphor by the Italian artist Gino De Dominicis that I really like: when you move your hand very fast, it looks as if it’s not moving at all. For me, this perfectly describes our moment. We are moving incredibly fast, yet everything feels strangely static. That’s why I’m interested in representing this idea of extended time, a present without a clear past or future.

Your works often arise from transformed everyday objects, such as helmets, drones, or protective structures. How do you select these objects, and how does their original function influence your work?

It goes back to my time at the academy. From the beginning, I was less interested in sculpture as a finished object and more fascinated by sculptural techniques, especially casting and molding. What mattered to me was the process. I started making molds and then discarding the sculptures, keeping only the negative, similar, in a way, to how Rachel Whiteread works with the negative of space. For me, the mold became a key concept. Negative space holds two things at once: the memory of a form that is no longer there, and the possibility of something that could still happen. This way of thinking shaped everything that followed. The works I make today, helmets, drones, and protective structures, are an extension of this approach. What interests me in these objects is their quality as containers. A mold, after all, is also a container. When it closes, it becomes a shell, holding both memory and potential.

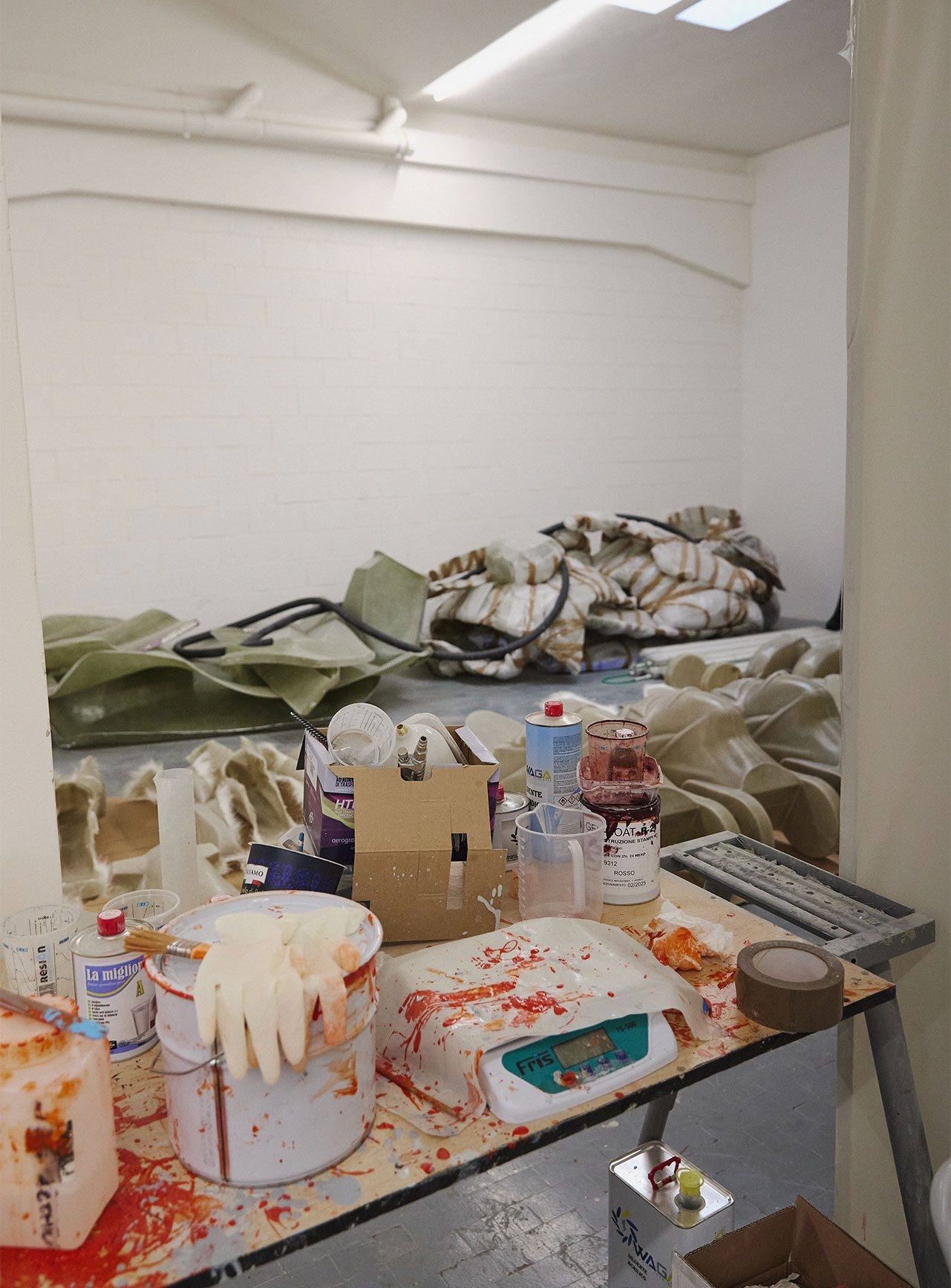

You mainly work with fiberglass. Why is this material important for you?

Fiberglass is interesting to me because in industry it has two main uses. It’s used to make very rigid molds, but also to produce things like boats, racing cars, or large containers such as silos. So it already carries this dual identity. Conceptually, it’s perfect for what I’m doing. Fiberglass allows me to create shells that are very thin but extremely strong. The sculptures are not solid; they are hollow. That makes them feel almost like ghosts. For me, there is a big difference between a solid sculpture and an empty one. A solid sculpture is just an object. An empty sculpture, on the other hand, is a container. It has a shape, but it also holds space. That idea of emptiness, protection, and containment is very closely connected to how I think about architecture, objects, and the environments we build around ourselves.

Did you always work with fiberglass?

No, I didn’t start with fiberglass. It’s a very difficult material to work with. You need specific skills, tools, and studio conditions, ventilation systems, and filters, because it’s extremely toxic. The resin, the fabric, everything. I’m completely self-taught, so learning how to work with fiberglass took a long time. There’s very little information available, especially outside of industrial contexts. It’s not an artistic material in the traditional sense. If you don’t work in big companies that use it, it’s very hard to access that knowledge. So I learned by myself, through mistakes, through experiments, watching videos, trying again and again. And even now, I’m still learning. I’m still growing technically.

What role does technology play in your practice?

Technology is central. I wouldn’t say it’s a problem, but it’s definitely the main protagonist of our time. It’s impossible not to take it into account, because it shapes almost everything: how we work, how we communicate, how capitalism itself functions today. The forms I work with, protection, isolation, and communication, are all deeply connected to technological systems. Technology has changed the way power operates, the way labor works, and the way we imagine the future. So for me, it’s not a theme I choose; it’s something that is already there, something I have to work with.

How much narrative do you build into a work, and how much do you leave open to the audience?

I think my work is very open. I don’t like to close the meaning too much or to suggest only one interpretation. I prefer to leave space for many possibilities. The ideas of negative space, negative time, no-time, and no-place, these concepts help the viewer to construct their own reading. My works don’t give answers. They ask questions. For me, the work is a way to invite the audience to reflect on contemporary life, on the present, on possible futures. And for that, openness is essential.

Would you say that your work is sometimes misunderstood?

Honestly, I don’t really care. It’s normal. People connect to different things, depending on their background, their sensibility. Not everyone likes the same artists, and that’s fine. I’m not interested in being fully understood by everyone. I don’t make pop art. If someone doesn’t have the tools or the references to engage with my work, that’s not a problem for me. It’s simply not for everyone, and it doesn’t need to be.

What are you currently working on, or what can we expect next?

My next project will be at Kunstraum Dornbirn. I can’t say too much yet; it’s better as a surprise. But it will be an environment. I want to place the audience inside a very specific condition. Not so much a space, but a state. A kind of liminal situation, between spaces, between times.

Finally, what drives you to continue making art?

I’m addicted to it. That’s really it. I can’t stop. I don’t know how to do anything else, and I don’t want to. I’ll keep working until the end of my life. Hopefully not dying too early from fiberglass (laughs), but I’m more careful now. I finally invested in proper filters and safety equipment. So yes, art is the addiction. And I’m fine with that.

Thank you, Davide!

Thank you.

Text: Livia Klein

Photos: Alice Piccin