Ernesto Neto is one of Latin America's paramount contemporary artists. His art is creating a sensual language that is universally understood. Spirituality, humanism, and ecology are among his principal concerns. Since the 1990s, his work has been characterized by the use of unusual materials and techniques pairing cutting-edge technologies with indigenous knowledge and traditional craftsmanship. Neto’s sculptures and installations often feature biomorphic forms and organic materials in which transparency and sensuality play a major role. Viewers can touch these works, walk through them, or set them in motion; in many cases, they also affect the sense of smell. The visitor is invited to concentrate on his or her own perception and interact with the work and its environment.

Ernesto, can you recount how art actually came into your life?

In the late 1960s, my father who was a mechanical engineer built a house, developed by Zanini Caldas, in an exclusive neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro called Joá, together with my mother who was then studying industrial design. The house was a master piece. It was my father’s vocation to build houses. Seeing all these houses being built from nothing became a school for me, and Zanini’s architecture was my horizon. As an engineering student I enjoyed the physics and mathematics class but other than that I felt quite lost. In October 1983 I abandoned my studies of engineering with the objective to study astronomy. I however did not pass the entrance test, so I left to Bahia for two months. In March 1984 I joined the sculpture class at Escola de Artes Visuais do Parque Lage in Rio de Janeiro.

You once said “I am sculpture and think as sculpture.” What did you mean by that?

When I began to study sculpture and employed my hands and my whole body to give shape to sculptures, I began seeing everything around me as sculpture. A sculpture involves structure, fluxus, balance, and movement. It refers to relationships and different states of being. It’s ubiquitous and brings clarity – even to things we cannot see.

Many of your installations look as if organically grown. They feel like natural habitats or shelters and resemble trees, nets, or cocoons. What are your sculptures telling us?

That is a very good question. Maybe you should ask them? (chuckles) I think that they are trying to say that we exist, that it is important to slow down, breathe, and sense our inner self. People rarely are allowed such moments in their hastened competitive day-to-day lives. I want visitors to be able to drive their fears away and concentrate on themselves in that very moment. I want them to become aware of their existence, to feel with their hands, their brains, and their hearts. And from there to feel the poetry of being alive.

Very often you seem to work with the concept of gravity – for example when you use nets, cotton strips, or drop-shaped elements that are suspended from the ceiling. What is the artistic intention behind this?

Gravity is a very intimate force. To me gravity is probably the closest expression of God – a spiritual power, a vital energy that holds everything together. It can hinder us, but it can also comfort us. Gravity reminds us of our existence by letting us sense the weight of our own body.

Visitors are invited to touch many of your works, walk in them, or set them in motion. At the same time, they make the impression of being very fragile and light. Why do you encourage physical participation?

It’s about offering freedom, but also about training people’s perception that being really ‘free’ involves taking responsibility for our decisions and our actions in this world. My walk-in sculptures are not just meeting places, they are also reminders that it is important to tread carefully, and to be gentle to one another. When you are not gentle with yourself and with others, things may tear, fall down, or break. By becoming more mindful of our actions and their impact on others hopefully we can reach a greater equilibrium and care in our society. It begins in ourselves.

Most often you encourage very close physical contact with your works. Yet, some works are not meant to be touched…

The line between what may be touched and what not is delicate. I feel it is an essential problem we are having in our time that we are insecure where that line is crossed. In an ideal world everything would be touchable. But our world is not like that. Things that are considered valuable become untouchable, including art. But not only that – even people due to their wealth, their rank in society, their power, or for other reasons have become untouchable. I don’t know whether such a condition is very healthy for a society. So the tactile aspect of my work may be understood as a criticism of this untouchability. Maybe one day everything and everyone will be touchable. Eventually, we may come to learn to touch others without hurting them by meeting them with love, and with our hearts.

To experience some of your works requires visitors to take their shoes off. Is it another aspect of teaching them to be mindful and respectful to their surrounding?

The effect of taking off one’s shoes has both a ritual and practical aspect. It causes us to stop and think whether we really want to go through the trouble of taking off our shoes just to enter the installation. Once we do take them off, however, we relax and we feel more connected with the ground we are stepping on. Through this immediate relationship with Mother Earth if you will we become more aware of our existence. Personally it feels great to me to be without shoes and, as you can see, I am without shoes right now as we speak. (laughs)

A peculiar quality of your artworks is that not only are they highly interactive, but they can also be smelled, as is the case with works that feature drop-shaped elements filled with aromatic spices.

What really let me become interested in olfactory impressions was when I noticed how rich in colors, texture and scent different spices were. Almost as if every single one had its own spirit. Smell is an innate sense that is able to touch us at a deeper level. Scents may trigger particular emotions, memories, and fantasies in us. And they can be quite powerful in attracting or repelling us, or in directing our actions. I believe that by being able to interact with a sculpture based on smell one will experience it in a very different way. To use one’s sense of smell also heightens one’s self-awareness and consciousness for one’s surrounding – our habitat: Planet Earth.

Despite being very experiential, your works are clearly not about superficial escapism. Can you describe what you would like to stir in a person who is interacting with your work?

I am trying to get people out of their everyday reality, to put them into a state in which they find time to breathe and think – to feel and to think with their pores actually. Some of my sculptures are really meeting places which shall help people feel themselves – venues of interaction and meditation where to develop a broader understanding of the world and its fragile balance. I am just creating the ambience and the conditions, but I am not here to direct people’s thoughts and feelings. Ultimately I want to encourage them to reflect on fundamental questions such as “What is really important in life?”

What in your view is the biggest misunderstanding when it comes to what’s important in life?

A common misunderstanding that persists is that materialism is able to provide a solution to all our problems and can make our lives happy and fulfilled. This notion that materialism can save us generates anxiety among people, letting them become addicted to consumption. Many people are in desperate need of materiality as they struggle for their subsistence, while others, behind walls and guarded by security have become untouchable, and are possessing too much. Aren’t we all people who are living in the very same moment together on the same planet? And is there no meaning to this fact? There is one thing that unites us all: humanity. Our lives should be more filled with thoughts how we might be sharing our love and our daily lives with each other, and how we could nurture what is between us.

What is your personal interpretation of “humanism”?

It is a good question what humanism actually means today. Originally, humanism was the birth of a heightened consciousness of our rational understanding of the world and our consciousness of human rights. But, to me, humanism has also brought forward the idea that humanity should effectively rise above other living beings on this planet. I think that this attitude has detached us from nature and made us self-centered. I firmly believe that we have forgotten that we are inhaling and exhaling and thus are living in communion with our surroundings and other living beings. In indigenous people’s view it depends on the vantage point who is referred to as the human being. If the jaguar focuses on you it adopts the human role. In one moment we may be the hunter, in another moment we may be the hunted. I feel we should develop a more balanced view with regard to our place in this world and embrace “planetarism” to grasp ourselves as a part this world.

What, if anything, might bring a tidal change to the state we are in?

I believe that we can arrive at a higher level of humanity and humanism – planetarism if you will – through practiced spirituality. After all, life on this planet ought not to be just about human beings, but about all beings and all form of life on this planet. My proposal is that we begin to be mindful in life and pay not only attention to what we the media feed us about catastrophes and negative events that serve only to amplify our anxiety.

What can you as an artist contribute in your view?

My role as an artist is not to exhibit our stupidities and inadequacies, but to show how beautiful we can be, how incredible, how gentle, and how full of love. I do believe that now is time for us to transform ourselves, to live up to our own integrity, and to be faithful to us in connection with the great spirit, no matter which cultural background we have or religion we follow.

In recent years, you have turned your attention to a new series of works that you have realized with the Huni Kuin, an indigenous community, living in the Amazon region near the Brazilian border with Peru. What can a “civilized” society learn from their cultural practices, spiritual traditions, and way of living?

Western civilization is something very recent, which started only 500 years ago with the Renaissance, and is based on intellectual knowledge that relies on the sciences and a rational view of the world. But there is another kind of knowledge: the highly spiritual knowledge of the indigenous peoples who have always lived in harmony and symbiosis with nature that has developed and accumulated over centuries. Their ways of knowing are different from scientific rationale, but not in the least less strong or powerful, and very humbling. Also a lot of beautiful poetry is engrained in indigenous cultures. Today I learned about the meaning of the word “Taruandê” from the language of the tribe of the Krenak. It describes a dance between the sky and the earth, and how in dance these two organisms interact and exchange. Such precious thinking is right around us. We only need to open up our hearts to it.

Are there any cultural or other aspects which you can particularly empathize with?

Indigenous cultures tend to place a stronger emphasis on equality, balance, and harmony – both societal and ecologically. There is a stronger sense of unity, of mutual responsibility and care for others, of time for each other among indigenous peoples. And the fact that they feel no separation from nature has taught them to deal with nature respectfully, without destroying it, in stark contrast to Western civilizations. I am encouraged by knowing that there are people nurturing this kind of energy and practicing and preserving this particular sophistication of relationship with nature and life.

At the end of June in association with the Fondation Beyeler you will show the monumental walk-in structure GaiaMotherTree in the concourse of the Zurich main station. The sculpture is made of colored hand-knotted cotton strips and extends right up to the twenty meter high ceiling. Can you tell us what thoughts entered this piece of work?

GaiaMotherTree pays homage to our Mother Earth, as a place that nurtures us and fuels relationships. The installation wants to stop the passer-by for a moment and plant a seed inside him or her. It is a place to be, to breathe, to dream. It wants us to feel alive, to feel how wonderful it is to be alive. So it is a place to share that joy, to share ideas and dreams, to think, to meditate, even to dance. It is a place to be!

A bustling railway station seems like an odd place for a contemplative artwork. How do you expect travelers and by-passers to interact with the work?

A train station is actually an interesting place, because in a station people are continuously arriving or leaving, in a state of going somewhere and arriving from somewhere. Our thoughts are either in the future or in the past. We hardly spend any time thinking about us actually being in the station. I like this notion of the “in-between.” Maybe GaiaMotherTree can fill this space. As a place to meet, to interact, and to meditate, and by its sheer presence, it may be able to act as a binding link between you and me, between us and nature, between us and civilization, and maybe between us and ‘God.’

Has there ever been a Plan B for you other than to pursue art?

You know, when I was a child I wanted to be an astronaut. By becoming an artist I probably took the easier route. (laughs). But since I did my first sculpture I never really had a Plan B. Art is my life. It is my church. It is where I find a way to connect. And it is how I express my joy to be alive, the responsibility I feel it is to be alive, and this gratitude to be alive. It is time to breathe, to embrace responsibility, and to transform ourselves and the planet. That is our moment. Now.

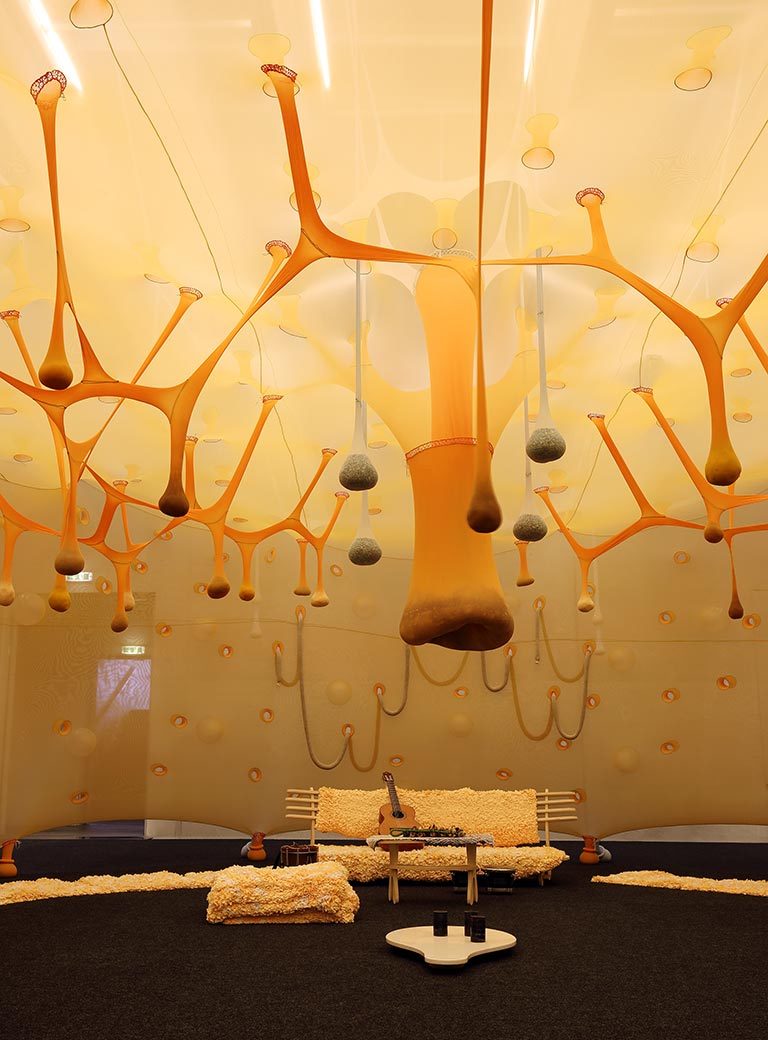

Ernesto Neto, GaiaMotherTree, 2018, Zurich Main Station, Courtesy of Fondation Beyeler, (c) Mark Niedermann

Ernesto Neto, GaiaMotherTree, 2018, Zurich Main Station, Courtesy of Fondation Beyeler, (c) Mark Niedermann

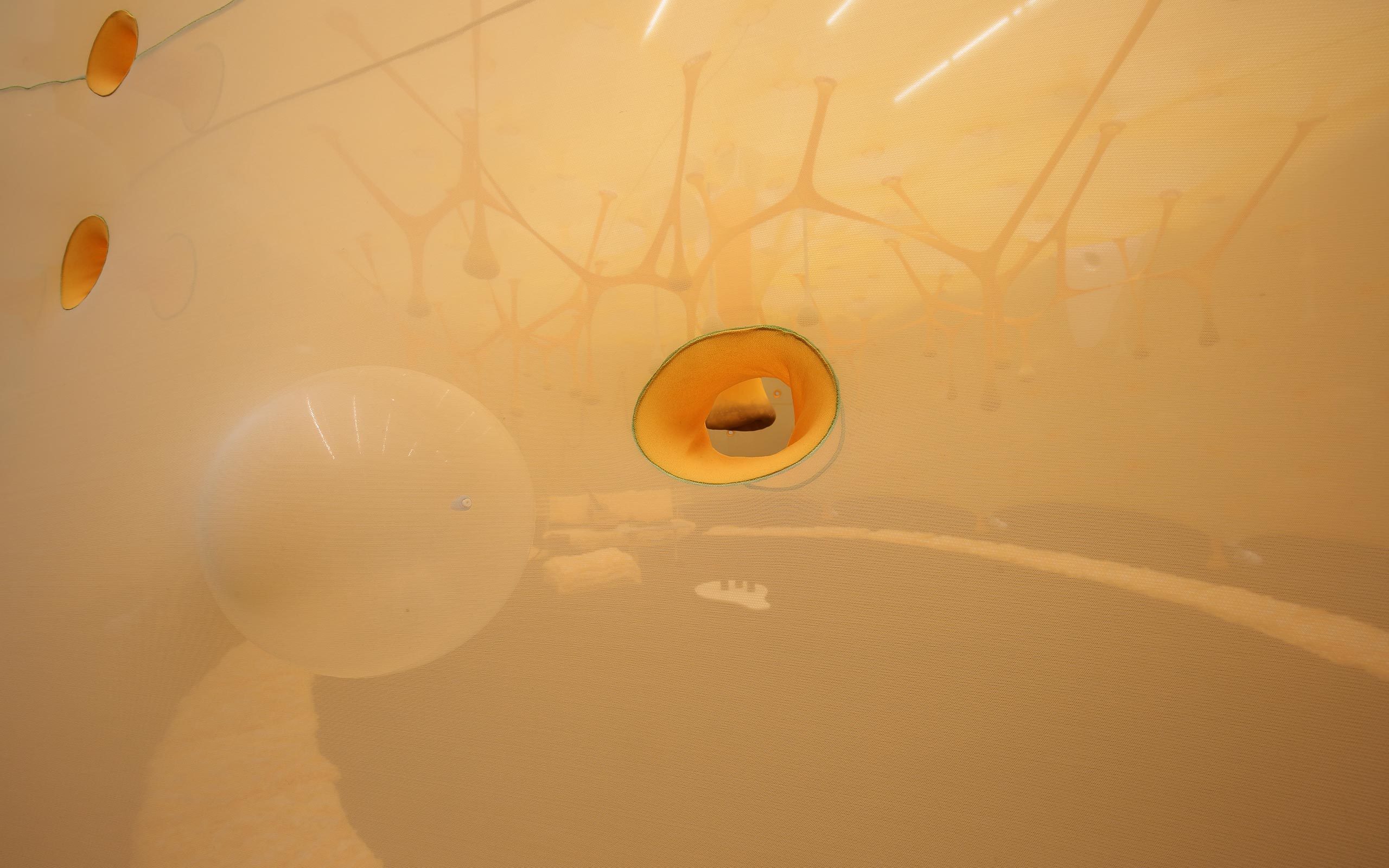

(c) Petri Virtanen, Courtesy of Finnish National Gallery / Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma

Interview: Florian Langhammer

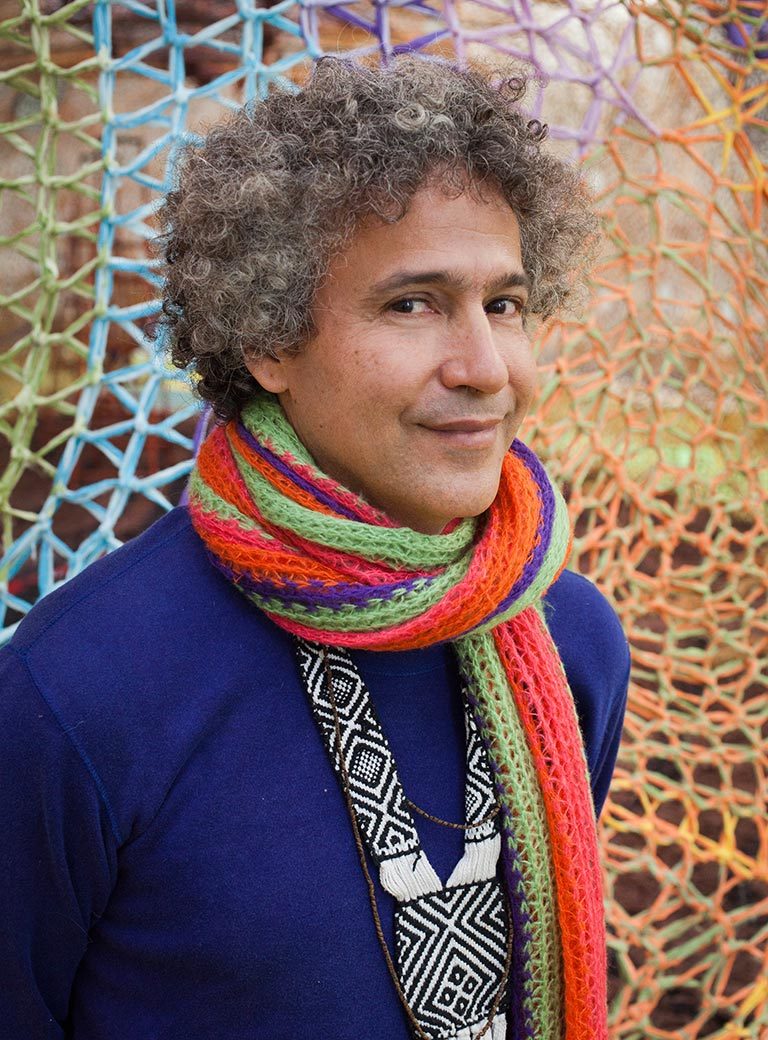

Title Picture: Ernesto Neto during the installation of Rui Ni / Voices of the Forest at Kunsten Museum of Modern Art, Aalborg, Denmark; (c) Niels Fabaek/Kunsten Museum of Modern Art, Aalborg; Exhibition views (if not credited otherwise): Ernesto Neto, Kunsthalle Krems, 2015, Photo: Christian Redtenbacher