Irina Lotarevich works primarily with metal to explore themes of housing, bureaucracy, and standardisation. Through modular structures and systems of measurement, she reflects on containment and the ways contemporary life shapes individual experience. Balancing minimalist form with layered conceptual reference points, her sculptures create a tension between control and playfulness.

Irina, how did you become an artist?

I guess I’ve been an artist for most of my life. I think I decided very early on that I wanted to be one — and when you’re a child, that often starts with something simple, like being good at drawing. That was definitely the case for me. As a kid, I loved drawing and I was good at it, and from there it just kind of developed. I basically chose that path quite young, and went to art schools throughout my life. Even early on, I was already in schools where you could specialise in the arts, so I was constantly studying painting, drawing — that kind of thing. But I didn’t really get into sculpture until I started my undergrad, in my twenties. That’s when I began to explore sculpture more seriously.

You live and work across different cities, like Vienna and New York. How do these environments influence your practice?

So, I grew up in New York. I was actually born in Russia, in a city called Rybinsk. It’s a medium-sized city. But my family and I immigrated to Brooklyn when I was eight, and that’s really where I grew up. Later on, I moved to Vienna to study and by now I’ve been in Vienna for almost ten years, which is a long time, so it’s also become a huge part of my identity. And artistically, I mean, these places have definitely influenced me a lot. A lot of my art education and my knowledge of contemporary art comes from New York — just being around the gallery scene there while I was growing up. But Vienna also really shaped my work in a different way. I actually only started working with metal after I came here, and I think there’s something about the aesthetics of Vienna that pushed my work in a certain direction.

Can you describe a typical day in the studio?

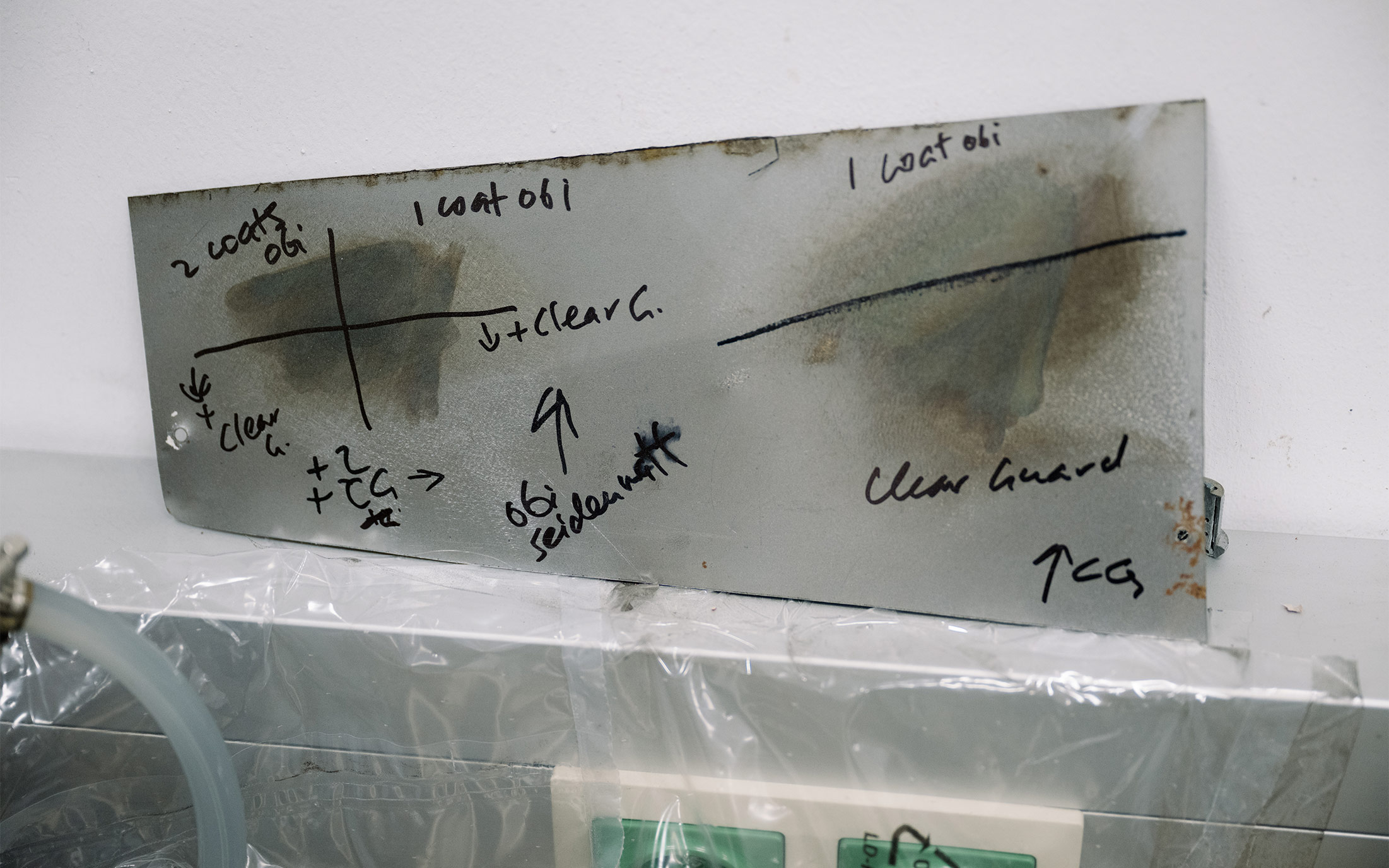

So, I split my time between working at the University of Applied Arts, where I teach in the metal workshop of the Sculpture and Space Department, spending the rest of my time in the studio. When I’m here, I really like to be in this kind of physical work mode, because I use my body a lot. Most of it is made by hand, and it takes a huge amount of time and labor. I really hate being on the computer and answering emails, so I try to avoid that as much as possible. I usually do it very early in the morning, just to get it out of the way. Then I come here, and I’m usually cutting something or sanding. I might be sanding for hours, or welding something — these are processes that just take a long time. Sometimes it’s three days in a row of sanding, for eight hours a day. So, it’s mostly a lot of physical labor, and not so much sitting around and thinking. Although I do think I probably need a bit more space to just sit and think sometimes. But for the most part, it’s very much a “production mode”. (laughs)

You have been working with metal for quite some time now, what draws you to this medium?

I really love metal. For a few years now I’ve been working almost exclusively with this material. Before that, I used to make sculpture out of all kinds of different materials — especially when I didn’t really know yet how to work with tools, or how to use my hands in that way. I was doing a lot of found object sculpture, or plaster casting — just very simple, accessible materials. But once I really got into metalworking, I kind of fell in love with it. I think people often stereotype metal as something that’s very hard and industrial, and kind of inaccessible. But I actually find it really flexible, once you know how to work with it, you can do so many different things. And I also like getting more skilled at it and being able to control it more. It feels like I could spend my whole life pushing into this material, and there would still always be something new to learn.

It feels like metal is constantly teaching you something?

Yes, I feel like I could keep going with this for many more years. It’s like the material is always teaching me something. And I mean, it’s the same with a lot of craft-based disciplines — because it’s so process-driven. There’s always a first step, a second step… you have to do things in a certain order. You can’t just be chaotic, you need a system for how you work. I think it’s also taught me a lot about patience and structure. And I feel like that comes back into the work as well — it’s reflected in it, in a way. And maybe at some point I’ll introduce other materials into the work if it feels like it needs that. Honestly, I’m happy keeping everything metal for now. (laughs)

When it comes to scale, how does it operate in your practice?

I had my most recent show at Sophie Tappeiner, and in that exhibition, there was one very large work — and the other works were smaller, more medium-sized. And I’ve done a similar thing in other shows as well, where you’ll have very small works next to very big works. For me, that shift in scale is a way of creating different reference points within a show or an installation. It gives you different anchors to orient yourself around. And because the scale keeps changing, it also becomes kind of unclear what the “overall” scale of the situation is; it’s constantly shifting. So I really like playing with that. And then there’s also a practical side to it. Smaller-format works are obviously easier to handle, especially because most of the time I’m working alone here in the studio. It’s just me, so it’s much easier to carry something if it’s smaller, to turn it around, to work on the other side, all of that. So that definitely has its advantages. Something I’ve been doing more recently is working with smaller parts and then assembling them into larger sculptures, kind of in a modular way, where the piece is built up from smaller elements. Like right now I’m working on something new: I want to make this work using these fortune teller forms, but there are going to be a lot of them, almost like wallpaper, like these studs covering a wall in a grid. The individual element is quite small, but through repetition it can create this much larger effect. And the idea is that it could theoretically be adapted to different walls and different spaces.

Are there artists whose work has shaped your approach?

Yeah, I don’t think there’s just one specific artist. It’s more like there are different people whose work I really admire, and that list is always changing. You know, sometimes there’s an artist whose work I didn’t really understand a few years ago, and then suddenly it starts to resonate with me. A good example of that is Mike Kelley. I didn’t really get his work until maybe five years ago. And then suddenly it just clicked, and I started to connect with it. He has this series called Educational Complex, which includes these metal mobiles. And in one of them, there are these model-like elements that resemble school buildings, based on his memories of the schools he went to. And as a sculpture, I think it’s just really beautiful, it’s simple, but also elegant. And conceptually it’s amazing too, because it feels like this kind of memory map. I also really like David Hammons, and I am a big Frank Stella fan as well.

And you always keep them close to you?

Yeah, they’re always on my wall. But also, I mean, I think I’m really drawn to metalwork and design history in general. For example, I look at the work of Pierre Chareau, a lot. There are different things that resonate at different times. What inspires me kind of shifts over time, depending on where I am and what I’m working on. So I think I have a lot of heroes, but not one specific person. It’s more like this mesh of reference points and inspirations.

How have your personal experiences shaped the way you work?

I mean, how can your personal experience not shape the way you work, right? My whole life path has gone a certain way, I immigrated to Vienna, and now I actually just got my permanent residency. I only just found out. So now I’m basically a permanent Austrian resident.

That is wonderful!

And then through this kind of series of choices, you eventually end up working within a certain aesthetic, or with a certain material. I think being an artist is really a step-by-step process, you try different things, and then little by little the path becomes clearer, or it kind of shapes itself in a certain direction. I’m always trying to process all of this in an abstract way through my work as well.

Housing and bureaucracy are recurring themes in your work. How do these ideas connect and intersect in your practice?

I’m working a lot with compartments and boxes. I think that connects directly to these themes. For example, in the Housing Anxiety works, the idea of housing has multiple reference points. Like, obviously housing as in a house, a place to live, but housing is also a technical term: when you have a machine and there are parts inside it, those parts sit inside a housing. So you automatically have this idea of compartments, of things being contained, organized, enclosed.

And I find that concept of compartments really productive to work with. In my most recent show, a work I made called Volatility is actually based on a stock market heat map. A heat map is this type of visualization, like a graph, where you have lots of different-sized boxes, and the size of each box corresponds to the size or value of a stock, different companies that make up the market. I found that visual language inspiring, but also it fit perfectly into what I was already doing in my practice. Because it’s basically the same logic, these different compartments that become more and more dense, and at the same time they’re also carrying information inside them. So, the sculptures I make can look very formal, they can seem very minimalist, even. But I think within these minimal-looking boxes or compartments, there are actually different layers of information and meaning that are contained inside.

You mentioned that you work with themes of standardization, can you tell us a bit about how you engage with systems of measurement?

My personal idea of sculpture is that it can actually be quite difficult to decide what the format should be, because sculpture is such an expanded field. It’s not always clear how something should look in the end, or what the final form should be. But for me, I really want the sculpture to have a form, to have physical presence, a certain weight, and a kind of specificity. So, what I’ve been doing over the last few years is using certain preset formats, like standardized formats, as a way to make those decisions. For example, in the work Volatility, with the heat map reference, the sculpture is made up of six panels that are 60 by 80 each. And this is actually a standard size that’s used for shipping pallets. For me it’s an easy way to determine the structure: I can arrange the panels in this modular system and let the work grow through that. In other works, I’ve used the size of my body as a measurement system, like using my own height as a standard measuring stick. In some more recent works, I started making pieces that have more curved elements. I heat up the metal and shape it more freely, kind of freestyle, and then I take that shape and build a container around it. So, in that case I’m determining the dimensions of the sculpture from the inside out, letting the form dictate the structure, and letting it grow that way. I guess it’s a combination of all these approaches, using commonly agreed-upon standards, but also letting the sculpture generate its own standards from within and sometimes using my own body as a point of reference.

I get the feeling that some of your sculptures evoke a sense of unease or anxiety, is that a perception you're aiming for?

Yes, I want my work to have this anxious, kind of oppressive feeling, something that feels a little bit constraining. For example, in some of these works you have elements that are placed inside containers and they’re being squeezed or compressed. And I want that to communicate this feeling of the individual being squeezed by contemporary life.

How do you balance feelings of unease with vulnerability and gentleness in your work, for example in the fortune tellers?

That’s also something I think a lot about with the fortune tellers — like, why I gravitate toward them as a symbol. It’s because they’re so nostalgic, and kind of naïve and playful, almost childlike. Everyone immediately recognizes them as something from their childhood, and I was actually really surprised by how universal they seem to be. No matter who the audience was, people instantly understood what they were and I think that’s pretty rare. There’s something really playful about them too, this idea of games of chance. It’s a little bit silly, like: “oh, which outcome are you going to get?” or “does this person like me or not?” (laughs) But at the same time, underneath that, the questions are actually very serious. I like that contrast, that tension, it’s something very simple and playful, but there’s also something hidden inside it.

What are your upcoming projects?

In March, I’m opening a solo show in New York at a space called KinoSaito. It’s a space that’s connected to the foundation of a Japanese-American painter, but they also host a range of different exhibitions. After that, I am taking part at a group show at Kunsthalle Wien.

Text: Lara Kastler

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt