Canadian artist Jeremy Shaw employs the aesthetics of documentary film and the language of alternative cultures to craft immersive audio-visual narratives and object-based installations. Inside his sun-filled Berlin studio, visitors are met with votive candles, found images of hardcore gigs, and triple Klein bottles — small elements of a genre-defying practice where nostalgia and dystopia are collapsed to elicit engineered phenomenological responses.

What a beautiful studio, Jeremy! Thanks for having us. Have you been working out of this space for a long time?

About two and a half years now.

Is there something that still feels new or special about it?

Definitely the light. And the ability to put more than one thing up on the wall at a time. I was never able to hang things in previous studios. They were too small and often had carpet on the walls for ad hoc sound dampening. One of them didn’t even have windows. So being able to put things up everywhere and really be immersed in my own world feels dreamy, it’s very generative.

Are there any objects that you like to keep in sight or available on hand?

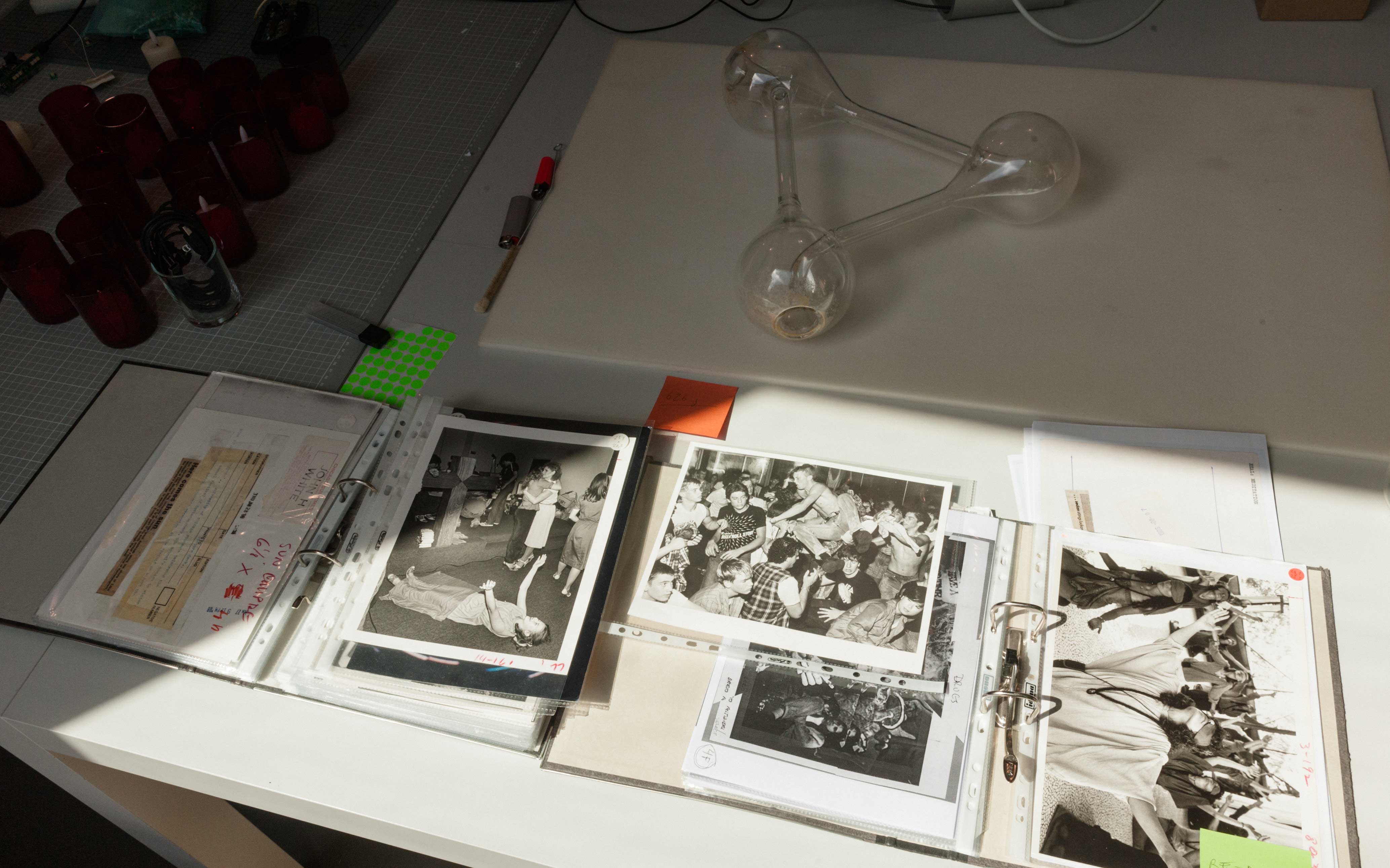

Often it’s just clippings from newspapers or magazines, or some of these found photos I work with. There are always all the things we’re in the process of putting together, placed and hung around the studio, but there’s no real go-to icon or anything that I can think of.

What are you currently working on?

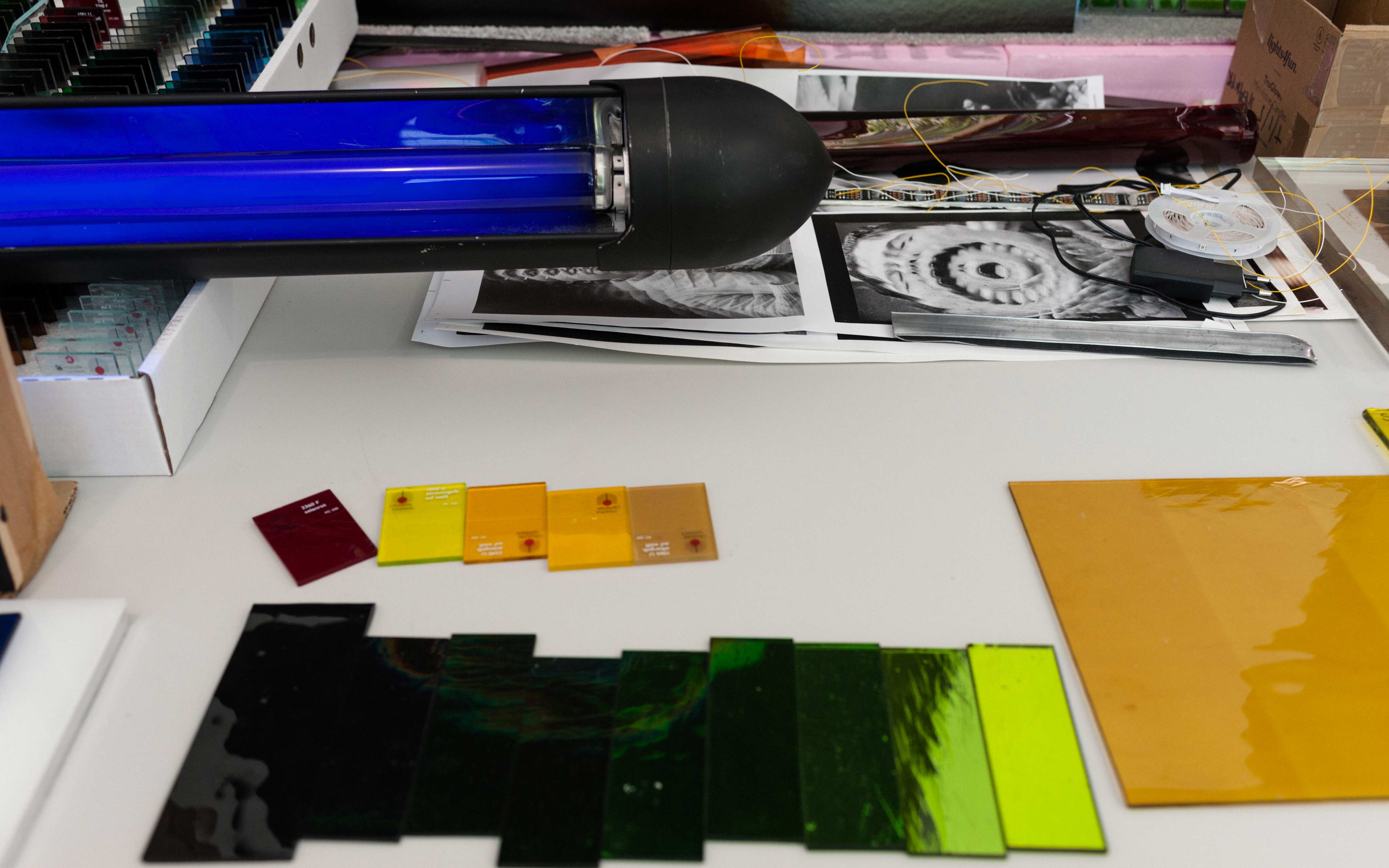

I'm working on a show for the Secession in Vienna right now. There will be a large-scale triptych of these stained-glass vortex windows set into a fake wall and a triple Klein bottle glass sculpture with vaporised DMT residue in its chambers. And there is a third piece, which resembles a large Catholic votive stand, which is why you're seeing red glasses everywhere. It’s a candle stand with 247 LED candles that looks somewhat innocuous and then transforms into something else, but feels very plausible just as a simple candle stand.

How does the piece transform?

There are just a small number of candles flickering randomly to begin with, but this slowly evolves to become a wormhole vortex animation that consumes the entire grid. Sound is activated in sync with the pulsing animation, and the sculpture becomes this complete hypnotic entity of its own. It becomes a kinetic work.

Religion and subversion often make an appearance in your work. Are these pieces part of a larger inquiry?

Yes. This very explicit reference to religious objects may be a new thread, but within an overall theme that I've always worked around.

If you were to describe that overall theme in the simplest terms, what would you say?

I think it boils down to faith and belief systems and how these are able to alter our reality. It’s a really large umbrella that incorporates many disparate areas that might not seem so related at first glance. From spirituality and hedonism to science and technology. It’s also largely about the potentially inherent human pull towards transcendental experience and the endless subjective interpretations of that term itself.

What determines the choice of media?

It’s case-to-case, whatever the idea demands is how it ends up manifested. The moving image works are really extensive projects, where the combination of ideas and concepts is messier and more alchemical. Here is where I often use the language of outmoded documentary, [cinéma] verité, et cetera, so as to be able to combine a super wide range of themes and elements into these succinct, autonomous works. When I'm making objects, it's more like extracting specific ideas from the moving image works and amplifying them into a physical form. The two are never very far from each other though, even if the handwriting doesn’t fully line up all the time.

How did you become interested in art as a way of tapping into these worlds?

Neither of my parents were interested in art, but I had a babysitter, a very close friend of our family, who was probably 10 years older, who definitely catalysed my interest. He was a very anachronistic character. As a teenager, he owned an old etching press and was super into Louis Armstrong and all sorts of antiquated things, pocket watches and tobacco pipes, really out-of-time for a kid in the 80s. He worked in this classic illustration style, like The Wind in the Willows, very twee, child-like, magical stuff. He would make all these amazing miniatures and paintings for us and create the most incredible environments when we were together, and had me drawing and painting all the time. He’s a very well-known artist and illustrator now, doing children's stories and watercolours — beautiful illustrations. His name is Charles Van Sandwych.

How old were you then?

I was probably about 4 or 5 when we met Charles. He lived just down the street from us and was around the entire time I grew up after that. So, I would definitely say that he was the reason that I realised that being this way was an option. To live as an artist and do your own thing, in your own world, completely. That's how I got into it. He was such an inspiration. Of course, there were many different phases after that.

Do you remember the first one?

In an artistic sense, the first genre that I subscribed to and got really deeply into when I was a teenager was graffiti. I also grew up skateboarding, so we were often filming, making little videos, etc. There was always so much creative energy going on within those worlds.

Is there something from the graffiti and skate phase that you still cultivate, or secretly practice?

Yes, sure. I was talking to someone about it the other day. I think that if you get deep enough into graffiti and skateboarding, there are things about them that are ingrained in you forever, long after you stop doing it. For example, no matter where I am, I'm constantly monitoring my environment for skate spots. You know, I'm always surveying architecture to see if it's skateable. And I will spot graffiti anywhere and everywhere I go. Even if it's scratched into the tiniest little top of a doorway somewhere, I'm going to notice it.

Almost like a way of seeing.

Yes, of looking. Or surveying. And adapting. They are both such adaptive acts.

Subcultures appear to play an important role in your work, making both real and fictional appearances in your films, including Quantification Trilogy and later Phase Shifting Index. What makes subcultures such fertile material for your work?

The notion of subculture, which seems really dated now as a term, was very important early on in my work, much before the Quantification Trilogy, as these were areas that I was drawn to when I was young, after leaving organised religion. I still sought that community, that connection to a mutual belief, the rituals, however they manifested. From skateboarding to raving to hardcore or whatever I was into at that point in my life, I feel like I was always searching for that connection. So when I started to make art more seriously, I was making work that drew from my own experience within and around these areas, making work that I wanted to resonate as much with those who were a part of them as it might for people who are into contemporary art. And I became more and more compelled by exploring the belief systems that formed within them, how they evolved, and what drives the need for belief. This eventually led to fabricating my own groups, alternative cultures, with more fantastic, science-fiction-like activities and belief systems.

Both your video installations and the object-based works, like the candle stands you showed us, play with the manipulation of familiar objects, leading to a sense of dissonance and rupture with reality.

Yes, I often work with outmoded forms or formats that we’re familiar with and have been generally trustful of, documentary film being one of them. If you see something that appears to be a documentary on 16mm or VHS, it's rare that you question its veracity. You would generally just accept that it's factual, that it happened and was told from an objective point of view. I find that with that presumption comes a lot of potential for manipulation. It’s similar with these religious object forms. They're very common, we’re quite familiar with them, so you don’t expect them to operate any differently than they always have.

How did you arrive at this approach to the viewer?

I really love when something catches me off guard. I love being tricked or duped by things — movies, songs, artworks. So that's something I've aspired to do with the works, and to the audience.

Can you speak a little bit more about your relationship with the audience? Some of your video installations take the surprise effect to an extreme, prompting unexpected ruptures in the audience’s own experience and perception.

Yes, my relationship with the audience has evolved quite a bit over the years. I’ve become increasingly interested in revoking the viewer’s autonomy, where all of a sudden the audience becomes implicated in the work. And really engineering this element. For example, with Phase Shifting Index, there is the attempt towards a kind of Ouroboros effect — you go from watching people in a trance with full autonomy to having that autonomy revoked and all sorts of engineered elements attempting to put you in some sort of trance.

Phase Shifting Index is currently on view at Hamburger Bahnhof and contains many of the elements we've touched on: video installation, sound, choreography, subculture, cathartic behaviour. How does that transition, from witnessing trance to experiencing it, take place?

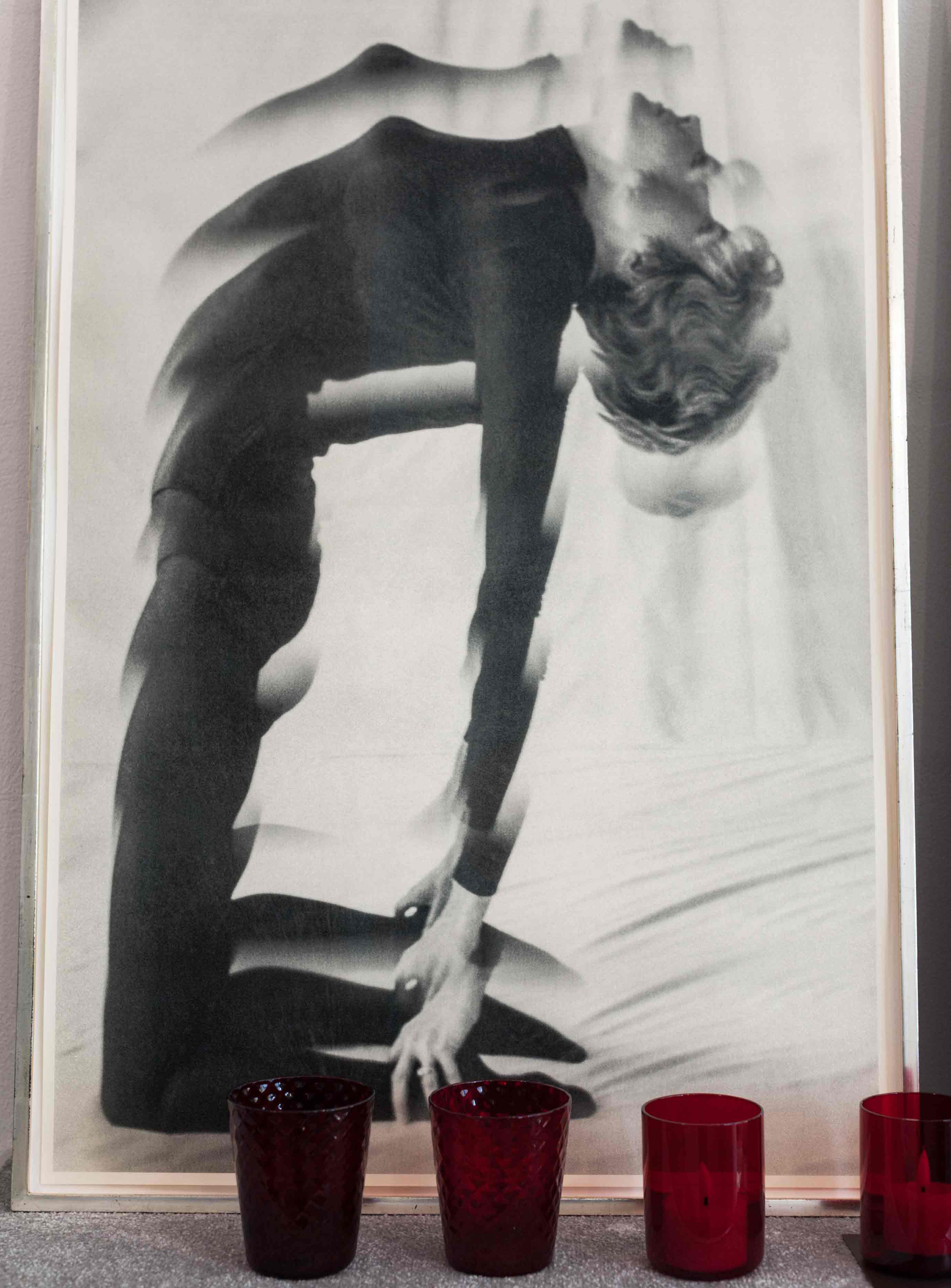

It’s a large room installation in which seven autonomous films are playing simultaneously. They each look like they're coming from a different period in the 20th century, from the late 50s to the mid-90s. The only connection is that each group has the same narrator describing their moment-based belief systems and their aim to physically alter reality. He also lets you know that they actually take place between 100-300 years in the future. You can watch each film on its own from a large bench in front of it with very directional sound, or you can sit at the back on a massive carpeted platform and take it in as a kind of tableau. The viewer has full autonomy of how to experience all these disparate narratives. But at a certain point, the films start to unravel and the subjects get more and more heightened in a kind of crazed, ecstatic state. A surround sound element starts to take over the entire space and builds and builds until finally all the films land in a fully synchronised choreography. So, all these disparate groups align across time and space, and everyone's doing the identical slow-motion dance, on 16-millimetre, on VHS, whatever. Meanwhile, the footage is strobing and the sound has become super loud. The viewer is basically caught in this immersive, hypnotic music video moment with no escape. And then it ruptures. There’s an actual rupture in the media from the outmoded aesthetics to a super contemporary digital format.

Why did you opt for such an explicit rupture in the media itself?

It’s my attempt at visualising that transcendental moment, you know, that actual transformation from one reality to the next.

Is there a drug or a form of rupture that still feels mysterious to you? Something you haven't explored, creatively, but feel drawn to?

I feel like I have tapped quite a lot of them! But of course, I’m constantly monitoring how people are engaging in cathartic forms of behaviour — both now and through historical research. I'm always learning about these things, and it never fails to be compelling. I came to a point, probably 12 years ago, where, as you'll see in my films, I began creating my own versions of cathartic forms of engagement through this accumulation of info. These really alchemical versions where maybe some somatic yoga practice is done in tandem with head banging while mainlining a synthetic nanotechnology used to open the faith receptors in the brain. And these are always coupled with fictional narratives that set up the ideologies and belief systems of the subjects as to how and why this behaviour evolved. What is it in reaction to or what is happening in the world that would make something evolve in such a way? I have been influenced by so many areas of these activities through history, but always aim to create something unique and autonomous through the pastiche.

Interview: Amelie Varzi

Photos: Kristin Loschert