A seductive appeal emanates from the abstract paintings of Sydney-based artist Jonny Niesche. Despite their minimalist ambition, they are showing a glamorous attitude. Similar to the situation of looking through a shop window and being apprehended by one’s one reflection, gazing at Niesche’s works the viewer is instinctively drawn into an interactive performative experience. We talked to Jonny about how coming to Vienna and meeting Heimo Zobernig made all the difference on his path to find his place as an artist, about his many “heroes”, and how Glam Rock came to influence his sense for color and surfaces.

Jonny, for an Australian artist you have spent quite some time in Vienna, and are now looking to open your second solo show here. Where does your relationship with the city come from?

Sydney University where I did my Masters in arts has an affiliation with the Academy of Fine ArtsAcademy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Some former students who had been taking projects in Vienna, among them Alex Lawler and Marita Fraser, who both work in London now, suggested it. As I listened to them talk about Vienna I thought “hey, this sounds really good”. Sydney was a bit frustrating for me at the time and I really felt I would benefit from getting away. In this instance, my work was a bit in a state of disarray and going through a phase of massive transformation, from figurative to abstract. So an overseas experience just felt right. So I applied to do a semester in Vienna in 2012.

How did you get accepted at the Academy of Fine Arts?

I was looking to develop my practice more sculpturally. Also I was interested in exploring ways of expanding space at the time. So, as an entry for my application I did a wooden glitter stick, that was leaning between two mirrors, forming a diamond in space by its reflection on the floor and wall. It was a bit of a Richard Serra-type of work, but executed in “glam”. Perhaps Heimo Zobernig saw my entry and thought it was funny or interesting. Anyway he accepted me in his class.

What do you think Heimo Zobernig saw in your practice?

I don’t know exactly. My work definitely wasn’t mature and self-assured at the time. Maybe he picked me as a “loose cannon” in the class and simply wanted to see what this person had. Heimo was very kind, but at the same time a brutally honest mentor. But he gave me some of the best advice I ever got from anyone.

What kind of advice did he give you?

Well I said that he could be very harsh and relentlessly open in his critique. On my arrival in class he asked me to do a little talk in front of the class. I put some images up and he said it would be short, only a couple of minutes. I ended up spending an hour and a half in front of the class, getting grilled. Heimo said that my work looked like a Tumblr blog. By that he meant that I hadn’t defined the parameters that would determine how my work operates and what made my work mine. He told me “You can do anything you want, as long as it adheres to your principles of what you want to make, and why. But you have to get these figured out first.” This sent me reeling. But it was one of the greatest things someone ever said to me as it really got me thinking. This thought process continued after I had returned to Australia.

How did you identify the rules and parameters for your work, as Zobernig advised?

I was worried for a long time trying to figure out "what it is" really that I do. I thought and thought … until I moved while looking at a glitter painting I had been playing with in the studio. And the glitter sort of "talked" to me. There was a response, one might say a visual conversation between the painting and myself. Dependent on the incidence of light in the room and where I stood the glitter was responding differently. It was this triangle of communication that stirred my interest. It was of a performative quality. So this got me thinking “How can I get beyond the flat plane of a painting and make it more performative and ever-changing, to renew the experience every time one looks at it. So I concluded, if a painting doesn’t do that, it is not mine.

So you decided your work would be defined by always being somehow experiential or performative.

Exactly. It became about how one is able to manipulate or cultivate an aesthetic experience within painting, and bring forward its performative qualities. I have been preoccupied with this question ever since.

Vienna and Heimo Zobernig were quite apparently a decisive moment in your development.

Yes, absolutely. I don’t know where I would be without this experience. A huge turning point. Vienna opened my mind. The exposure to Heimo and my peers was really helpful. In addition to that it was also the experience of being abroad with our son, who was 10 months old at the time. Having a child changes your focus completely. Your thinking about how time operates is quite different. And you really make more use of the time that remains other than that taken up by changing nappies all day. (laughs) But seriously, I firmly believe that at that point my work started to get better. The situation seems to have sharpened my sense of what is important.

Did you know Heimo Zobernig before your arrival in Vienna?

It is a bit of an embarrassing thing to say, but no I didn’t. Once in Vienna, the more I learned about him and his practice, the more interesting the interaction with him became. His work is such a deep well of ideas. He has an unbelievably strong practice, and it was exciting to see the diversity of ways in which he playfully explores his ideas while at the same time keeping it very focused and compelling.

Generally speaking what motivates an art student to enter a class held by a particular artist? Does one secretly want to emulate this person’s work?

No, I would never want to study with someone whose work I would want to emulate in any way. I would want to study with one who has really strong motives for making work, and is able to pass on experience, systems and ideas. Which is exactly what I think Heimo does for his students. I don’t think Heimo wants to reproduce a lot of new "Heimos”.

What characterizes a great mentor to someone who seeks to study art?

It’s someone who is able to look at someone else’s practice, recognize something good within them as an artist and nudge him or her in the right way to help him find his or her own voice. Both Heimo Zobernig and my supervisor at Sydney University, Mikala Dwyer have been excellent in that regard. Both don’t churn out little imitations of themselves.

Let’s talk about your practice today. What experience would you like viewers to have with your work?

Hopefully, when you experience my work, it is more like an event, where the viewer has to be present to make it possible. By the reflective surfaces and glitter the viewer becomes present in the work. It is this desire-like situation when you are looking through a shop window at something you want, and at some point you are apprehended by the reflection of yourself within that situation. That it an interesting point I like to play with.

Looking at your work, one is not immediately able to tell whether it is translucent or solid.

I have been looking at Dan Graham who works a lot with translucency in his spatial installations. This led me think about experimenting with optics and exposing processes of perception. How looking through a work itself, the experience of the space, and the other viewers experience within the same work could be the central functioning form. At some point I pulled out an old used silk screen and looked at remnants of images, people, and the surroundings through the screen. This gave me the idea of working with “Voile”, a transparent fabric which serves as another layer on top of the surface of my works, printed on and then stretched over acrylic mirrors.

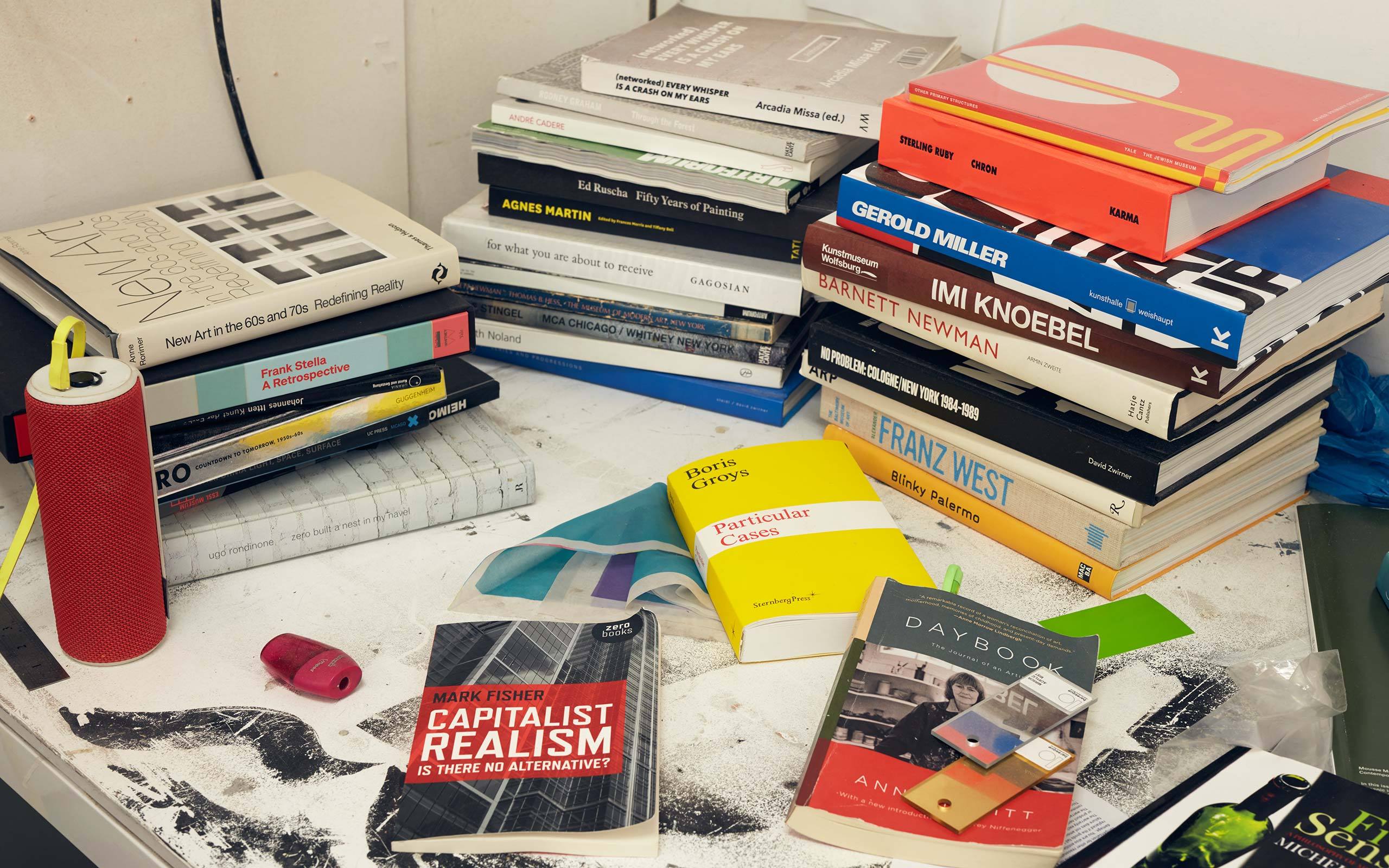

You once said that you were interested in making references to art history. Obviously the Minimalist movement comes to mind.

I like to look back in time and to look at certain eras and particular painters, thinking about how I can take the language and ideas prevalent of the time and look at it through my own subjectivity, in a performative way. Besides by my own subjectivity of course, my work is of course heavily determined by the viewer’s very personal and situational experience of the work and any subjectively perceived quotations.

Light and color seem to play an extremely important role for you. Some colors evoke the association of a sunset at a beach in California.

You are very spot on there. California indeed has had a movement which was preoccupied with light and space. Among its most prominent representatives were Larry Bell, Robert Irwin and James Turrell. I am mad about those guys. The Australian East Coast has a similar climate as California. And interestingly we get the same sunsets. A lot of my work is indeed based on the feeling of the sunset looking to the East. They are special in that they produce soft and gentle hues – quite the opposite of these Western bright sunsets. Australia is such a vast landscape you feel the sublime here in an incredible way.

So the hues of color that characterize many of your works are actually sunsets?

Not really. I would say they are inspired by the feeling of sunset, and the feeling of color they generate within me, along with my personal experiences and memories. I play with colors in Photoshop until they generate something in me that talks to that experience. But they are not sunsets per se. They are just gradients. But gradients that hopefully give a special quality. Like an immersive void that somebody can disappear into to contemplate…

When you speak of personal experiences and memories, can you make an example how these have influenced your artistic working method?

You know, as a boy, I was not so much influenced by the masculine color charts from hardware stores like many artists have quoted. Instead, my mother had dragged me along to the cosmetic departments. I fell secretly in love with the colors I found there, the mirrors, the reflective surfaces. It was unbelievable. It was the glam era. It was a highly influential period in terms of the way that I responded to color and surface. It was kind of a secret and guilty pleasure as I knew that as a young Australian boy that was not what you were supposed to like. Australian society was very blokey in the 70s and 80s.

So there is a very strong connection between the “glam” period and many of your works?

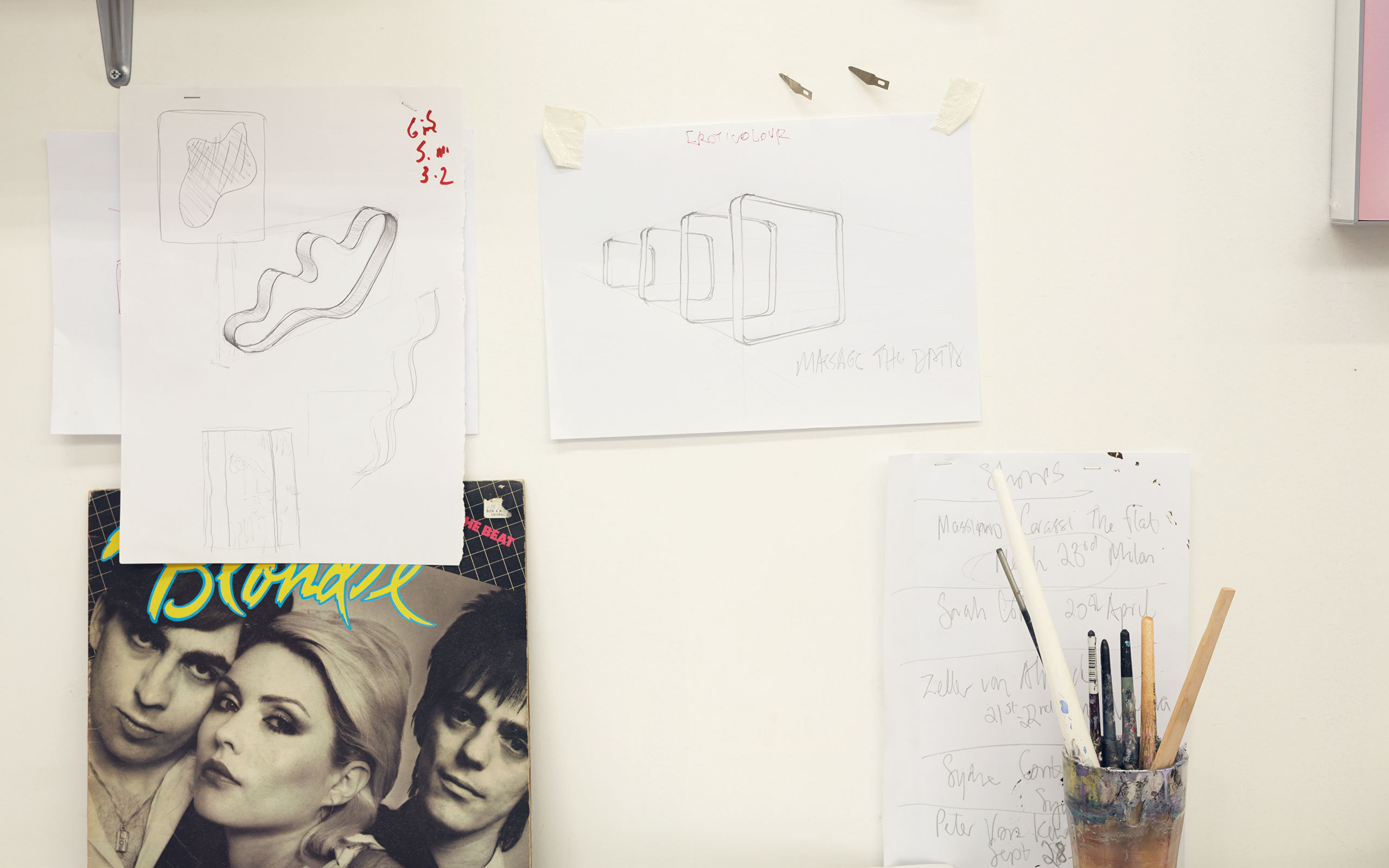

Oh, definitely. Glam has always been an element that excites and interests me, not just its visual expression. With Glam Rock, there was also a very strong musical style in that period, with David Bowie and Ziggy Stardust at the forefront. For example, my show title Picture This at Station Gallery in Melbourne was based on a Blondie song. Debbie Harry, the singer of Blondie, was a woman I had much affection for musically and visually as a young man. I took digital samples of her eye shadow, make-up, and outfits from photographs from the late 70s, and created a color palette for the works.

To understand and talk about art many people tend to compare an artist to another one they know, such as “Oh, his work just looks like …” Do artists like their work to be compared?

I know that not every artist would agree, but I don’t mind quotations at all. This was something really nice about Heimo’s class. Each week a student would present their work. Everyone in class would discuss it often saying what other artist or artwork it made them think of. The whole class could be about quotations and intersections. My works are always laden with quotations, even if many are quite loose or obscure.

Talking about influences and quotations. Do you have any personal heroes, apart from the artists you already mentioned?

I had a show in 2014 that was called Too Many Heroes, because there are just too many heroes for me. (laughs). Isa Genzken comes to mind as an artist I have great admiration for. And, although there is not much obvious aesthetic connection between his and my work, Martin Kippenberger is an artist I have looked at quite deeply. You get so much from studying different artists which are not necessarily so much connected to your own work aesthetically as it lets you think of different ways of making. John Armleder is super important for me as an artist who is playful with quotation. And of course the great minimalists like Donald Judd or McCracken, especially from a perspective of taking painting and sculpture and finding a space in between these disciplines, for example by leaning a light plank against a wall. That was a decisive maneuver in linking painting and sculpture. Also the “fetishism of surface” by the Californian artists, among them Doug Aitken, is something I am really interested in. I think quoting something is about giving it life again.

Do you see a particular role for society being an artist?

I think that role is quite different for each artist. I have been very careful to steer of politics within my practice. I explore areas that I hope I have something to add to. As an artist if I am able to create an aesthetic experience that can have a transformative or changing effect on the viewer, outside of his or her daily routine, then my job is done from my perspective.

What does Monte, your 5-year old boy, think about what you do?

I don’t see him take much interest in my work, actually. He doesn’t really have an opinion about my work. But I like watching him make things. And I see the same obsessive moments in which he completely disappears into creating something, which is when you can’t hear anything from him for hours. But he loves going to the studio and collecting the material I am using like little pieces of mirror. He is then taking his finds back home, playing with them, turning them into his own thing, which is wonderful to watch.

You live and work in Sydney, with two galleries representing you there and in Melbourne. Which of the cities has the more exciting art scene to offer

Melbourne and Sydney are both artistic centers in their very own way. Both produce very good artists, but very different artists. They are very different types of cities. Melbourne is more interested in its heritage. Over time it has kept its beautiful historic buildings and seems to have invested more in cultural production, with some great universities to study art. Sydney is kind of the opposite. It is a landscape in which people change very quickly. It is a very cyclical, volatile city. Real estate has become insane in Sydney, and most artists can no longer maintain their studio in the inner city anymore. Many Sydney-based artists tend to go overseas to return later. Melbourne’s artist scene on the other hand is more self-contained and organic in terms of the artists it is producing. There is lots of competition and comparison between the two cities.

You mentioned that in Sydney it is becoming more challenging to maintain affordable studio space. How do you manage?

I was able to team up with some artist friends. Together we rented a 400 sqm space. We built dividing walls to create 8 studio units and invited other artists. We are just sharing the costs, without making money on the division. Prices in Sydney have become insane enough and we don’t want to join in this development. It is all but sure that we can stay in here forever, but as long as we do have it we consider ourselves lucky.

Comparing to Sydney, how did you experience Vienna’s artist scene?

I have to say I love the art community in Vienna. It has an almost village-like atmosphere, very closed and contained. Vienna has a certain cosiness despite its almost 2 million people and it being a very cosmopolitan city. And the scene is full of many remarkable artists.

Vienna fascinated you enough to come back for a second stay in 2015.

I received a fantastic opportunity to do a residency there, facilitated by the Fauvette Loureiro Scholarschip from Sydney University, being able to show in the project space of New Jörg. During my residency many people who looked at my work told me that “stylistically it was “suitable for Los Angeles”, which bothered me slightly as I had just arrived for a 7 month stint. Heimo said to ignore that and told me “Keep going, and just do what you do.” So I thought I should sort of play with people’s perception and bring America to Vienna. The show was called New Jörg, New Jörg and my text paintings read “NY” for New York and “LA” for Los Angeles. And there was an angular-shaped painting called Coast-to-coast which was positioned in the gallery to catch the exact angle of light when the sun set.

Who is collecting your art?

Mostly Australian collectors so far, but interest is growing abroad which is of course great. Among others I am getting more interest from French collectors and the German-speaking area. The thing that really excites me is that I am able create art for myself, without having to spend much thought of the commercial aspect, as I am luckily finally able to sustain a living for my family without any jobs on the side.

Your second solo show in Austria, titled Splitting Image, is coming up and will open in June at Zeller van Almsick. Can you reveal what it will be about?

The show at Zeller van Almsick will be my very first solo show in a gallery outside Australia. I have been looking at my experiences with color during my stays in Vienna, as well as the notion of kitsch. In a way Vienna can be an extremely opulent and kitsch city with its bombastically gold and white statues shouting in the middle of a space or a park. When I lived in Vienna I was close to the Stadtpark. Walking through the park one could not avoid the golden Strauss statue, which burned itself into my brain. The show will have a golden-framed mirror-painting, spinning as a reference to the Waltzes by Strauss. I was also struck by the touristic imperial dinner plates which show portraits of Sissy with a golden brim around the plate. The golden-framed paintings which will be on view are a playful take on these plates, and the notion of portraiture in a performative experience. You see your own portrait in the “dinner plate” so to speak, but in within a hard-edge minimalist experience.

Has there ever been a Plan B to art for you?

I actually used to be a musician playing in hardcore bands in New York. I only came back to Australia in 2001 at the age of 28, after a decade of musical obsession. I never really got by as a musician and had been working in restaurants the entire time. When finally some potential of success turned out I realized that I would be getting myself into a life on the road. And I was aware of the potential for addiction to all kinds of substances. I am a real home kind of person. Once I started to understand what my life was going to be like for a long period of time I realized it was not what I wanted, coupled with the fact that my ex-wife and I were probably the worst combination in the world. (laughs)

Coming home, I was trying to work out what to do with myself. I started renovating my parent’s house and helped them sell it. On a whim I took the “for sale” sign and decided to paint on it. I started buying more paint and canvases and moved to painting from 2003 and over this period developed a really serious interest in art. I realized that I really didn’t have any context for the work and no education. I knew that, if I really wanted to take it seriously, I needed to go and study, learn about art history, and find out if there was a place I would fit in. Because of our child it took me longer than the average student. So I did 7 years of university in a row, including my time overseas, in Vienna.

In a way art seems to have been your “Plan B” then, and it sounds like it turned out to be the better option.

I think I am a better painter than a musician. (laughs) Doing music would have exhausted me too much. It was painful in a way. I took music too personally and all the time felt that I was giving away too much of myself. With my art there seems to be more distance. Even though I am being super subjective, I think I am more on top of it. And I feel very comfortable. I love making things, it is really exciting and invigorating.

It takes a lot of guts to abandon something you actually liked doing, despite all implications, and to jump into the unknown, which was exactly what you did when you left New York…

Yes, it was a big job. It took a while for me to come to terms with it. But I am glad of where I am now. I love my job. The weekend ends and I can’t wait to jump in the doors of my studio. I see other friends or neighbors who groan at the thought of a Monday morning. And I am the opposite. I can’t wait for those Mondays to begin.

Interview: Florian Langhammer

Photos: Hugh Stewart