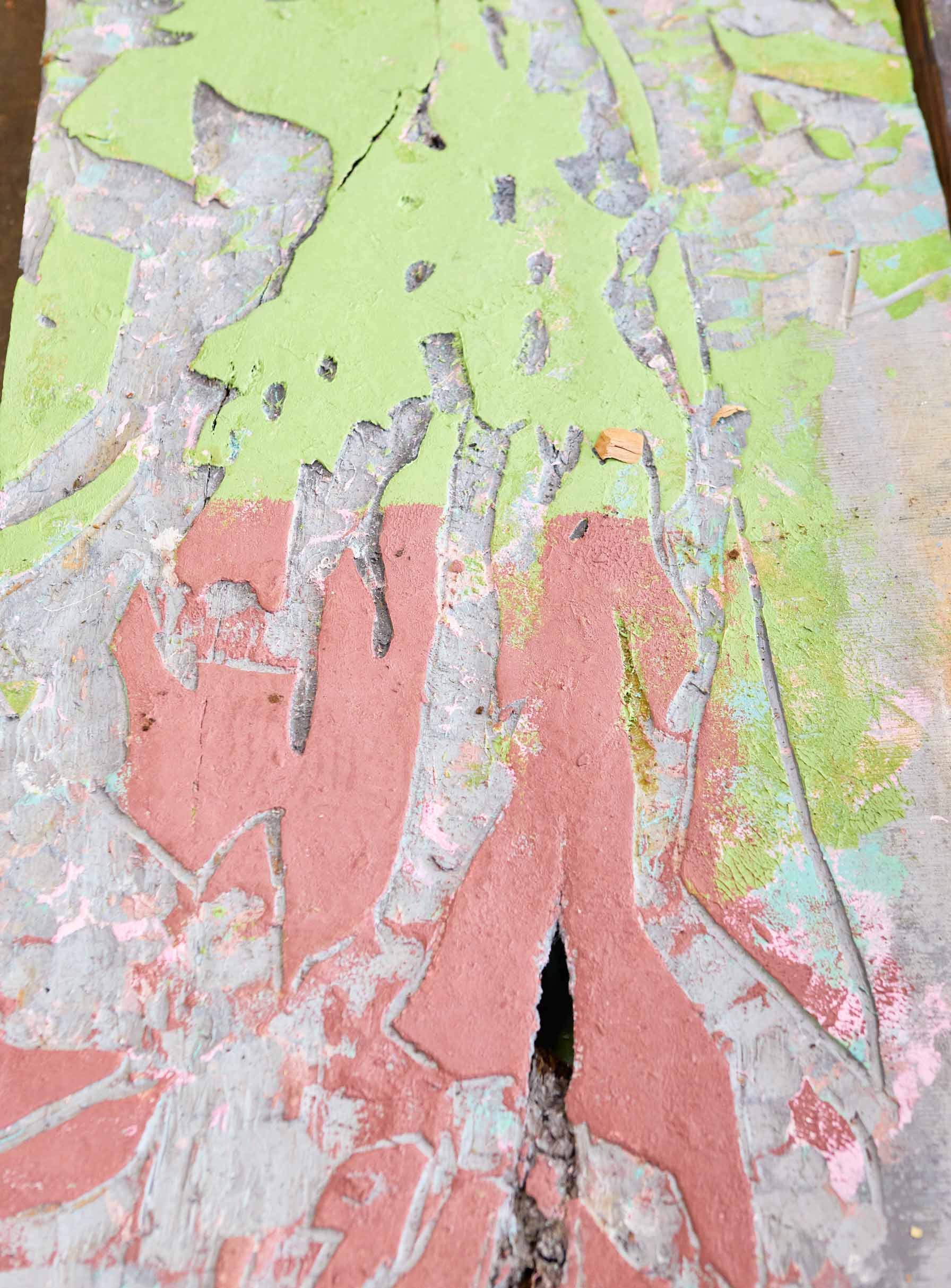

Lena Göbel lets her rural roots pervade her art. Her motives are nature, the environment and the people close to her; formally too, she translates country life into her work. For her woodcuts she uses printing posts from pearwood or spruce, and the print itself seems almost archaic in its simplicity. She then paints over it, adding abstract elements.

How did you become an artist?

My parents were both artists; and this is why I never wanted to study art, just so as not be like them. However, when I was fifteen, I discovered woodcutting, which my parents had never done. And I liked it so much that it would have been stupid not to go for it! Therefore, I had to commit myself to art.

Did you think that the bar was set very high?

Sure. As a child, I always thought: what if an artist runs out of ideas? Because I had not understood yet that it’s not about ideas, but about whatever catches your eye.Whatever comes out must already be inside of you! But I needed some distance, and so I went off to Berlin after the Academy for five years. One needs to do one’s own thing.

But was or is the approval of your parents important to you?

Very much so. I kept sending them pictures of my work and wanted their opinion on it. In the sense of: please pay me homage (laughs).

You grew up in Frankenburg am Hausruck, a rural place in Upper Austria. It is often the case that artists coming from the countryside want to free themselves from it. This does not seem to be your case, you even live back home now…

That is true, I now co-live with my mother.

The rural aspect is very present in your work. Do you start your working process with woodcutting?

Yes. First, I carve into the material. I sometimes use printing posts from pearwood, which is a bit unusual. This might have to do with the fact that I grew up in the countryside and therefore like to use natural materials. In Bad Gastein for instance, where I worked on architecture, landscape and history as part of a residency, I used spruce. In my eyes, the printing post becomes its own sculpture.

How do your carved motives come to life?

The model is a sketch or a photocollage. The woodcut gives me the idea of a motive, the concept of a content. Often, it is about human-animal hybrid creatures, about a relation to nature. I think about how humans influence their surroundings. Or I concern myself with technical motives like in Bad Gastein, which I translated as a kind of Manhattan in the Alps. This sketch I then carve into the wood, followed by a test print.

Because you might still change something?

Yes. With people or animals both, it is not easy to see their facial expression in the carved wood, one needs to print it several times. I think facial expression is important, therefore I might change the eyes or the pupils to emphasize it. But to be honest, I think this might be one of the reasons why painting has become part of my working process. This is how I can “better” the expression of faces. Painting allows me different moods, or realities.

Do you think woodcut is more static?

Exactly, more static and striking, the lines are defined and angular. Painting allows for color transitions, softer, moodier gestures. Woodcut is more about expression, it’s expressionist.

This makes one think of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner or Werner Berg…

Absolutely! Woodcut is like a stop. Regarding painting, I see it as something more sensitive.

Once the print is done, you will glue it onto the canvas and start with the painting. From a hierarchical point of view, what do you place higher? Painting or woodcut?

It used to be the woodcut, the print. It provided the frame for the rest of the work. But now, everything is equivalent. Depending on how much the picture is asking of me, the valence is different, I will determine it in the moment of creation.

In your works, painting takes on a blurred, fuzzy aspect…

This complexity is important to me. I paint over my print. And I like it when the result is a complete picture, a compact work. But the viewer should be able to make out the different steps in my work, which have demanded a bodily effort, like carving. Even if you don’t know much about my work, you should feel something when looking at it. This emotional part is really important to me.

What is your preferred activity – carving or painting?

That really depends on my mood of the day. Painting might be a quieter activity in the evening, once it gets dark.

We have spoken about the form, what about the content?

Themes and motives are crucial to me; things I am in touch with. For instance, how people act with nature, and what the result of this interaction means for a place and a society.

Where does your interest for “old” stories come from?

Probably from the fact that I grew up in a 400-year-old house that has been in my family for a century. It used to be an inn, run by my grandmother, and my grandfather’s locksmith shop was just next to it. Because my parents were both artists, in my personality I unite the historical and the crafty-arty.

This doesn’t sound like a typical life in the countryside?

On the one hand, because of the inn, I was really in the midst of village life, but on the other hand, I had these artistic parents.

Did you want to translate something from this traditional milieu in which you grew up into contemporary art?

Absolutely. Although my family was a traditional one thanks to working at the inn, nothing was ever bourgeois or narrow-minded. For instance, I can prepare a mean roast – these are values that I think are important to pass on. The same is true for crafts, like the old locksmith shop.

The Church is also part of that, when one grows up in the countryside, right? Is this where work titles like Trinity come from?

In the countryside, church is just a part of life, even though it never played a major role in my family. But when running an inn, you are just living it anyway: after Sunday church, the farmers would sit in the main room, and the women gather in the kitchen with my grandmother – “Kuchlweiber” or kitchen women, as we called them. Wakes also took place at the inn, we were quite known for that (laughs). One was just part of it all. And this is why I work with those themes. In general, one can observe a lot when growing up in an inn…

And observing is a key characteristic of artists!

The inn would allow me to do social studies! When I was a child, sometimes the strangest figures, drunks, would stop by. They would then sit in our old wooden room. And my mother had to come and get me…

What did you learn there?

That these marginal figures are actually quite lovely. The alcoholics really liked my brother and I… And I am sure this has marked me: that these people from the fringes, who were no doubt being sent away everywhere else, still got something at ours.

I hear a lot of love for people in what you say. However, you often depict them with an animal head?

Ah, that is my misanthropic side (laughs). When it is about individuals or very unique people, I can relate. But when I think about humanity as such, I would prefer the animals to reign. They fascinate me, and so I came to the humanization of animals – or in reverse to showing the animalistic in humans. When you put an animal’s head onto a human being, it might act differently.

Would you like to give animals more freedom to act?

One can learn a lot from animals. They act per instinct and not for their advantage, they are not commercially motivated. I am thinking a lot about the fact that research money is being invested in very questionable things: fluffy mice that look adorable – and are potentially the first step toward bringing mammoths back to life. On the other hand, there are living creatures that do not get the protection they need. Wouldn’t it be better to save animals from extinction first? Just a thought…

Is life not being appreciated enough?

Why do we have to use life so insensitively, so lavishly? When you think of the shredded chicks… The problem with humans is that they don’t respect life.

Does your respect for life maybe come from having grown up in the countryside?

Maybe, but it also has to do with growing up or getting older, because you realize the fleeting nature of things. In my house, being wasteful was always a tabu. In general, I do think that it is more about a certain kind of education – not an academic one, but one that is being communicated by parents and grandparents…

The education of the heart! Don’t you communicate this kind of education through your art?

That is what I would like!

Lately, your work seems to veer more into the abstract?

Correct; but everything is always very free in my work. There are artists working figuratively; and when something abstract emerges, they then stick to that. In my work it can happen that something figurative will sneak back into the abstract at some point. It is more about an emotional process, a flow.

What makes your art interesting is that form and content overlap; the archaic, rural is present at the same time as a motive (nature, animals) and as a working process (woodcut).

Yes, this is exactly what I mean: the content is multilayered and overlaps with the form.

Is this the red thread that holds your work together?

Yes, for a long time, I have worked with themes around nature. And I have a soft spot for people on the fringe in the countryside. For 20 years, I worked with those motives but never knew why. I just did, and it felt authentic. It was only later that I understood where it all came from. Sometimes in life you realize that you’re doing something without knowing why, but that it is still important you do it. It is an impulse, a need to get a work out. Other people can interpret it, and it is important that the work is being seen. Without a viewer, it doesn’t mean anything.

Speaking of seeing: What are your new projects?

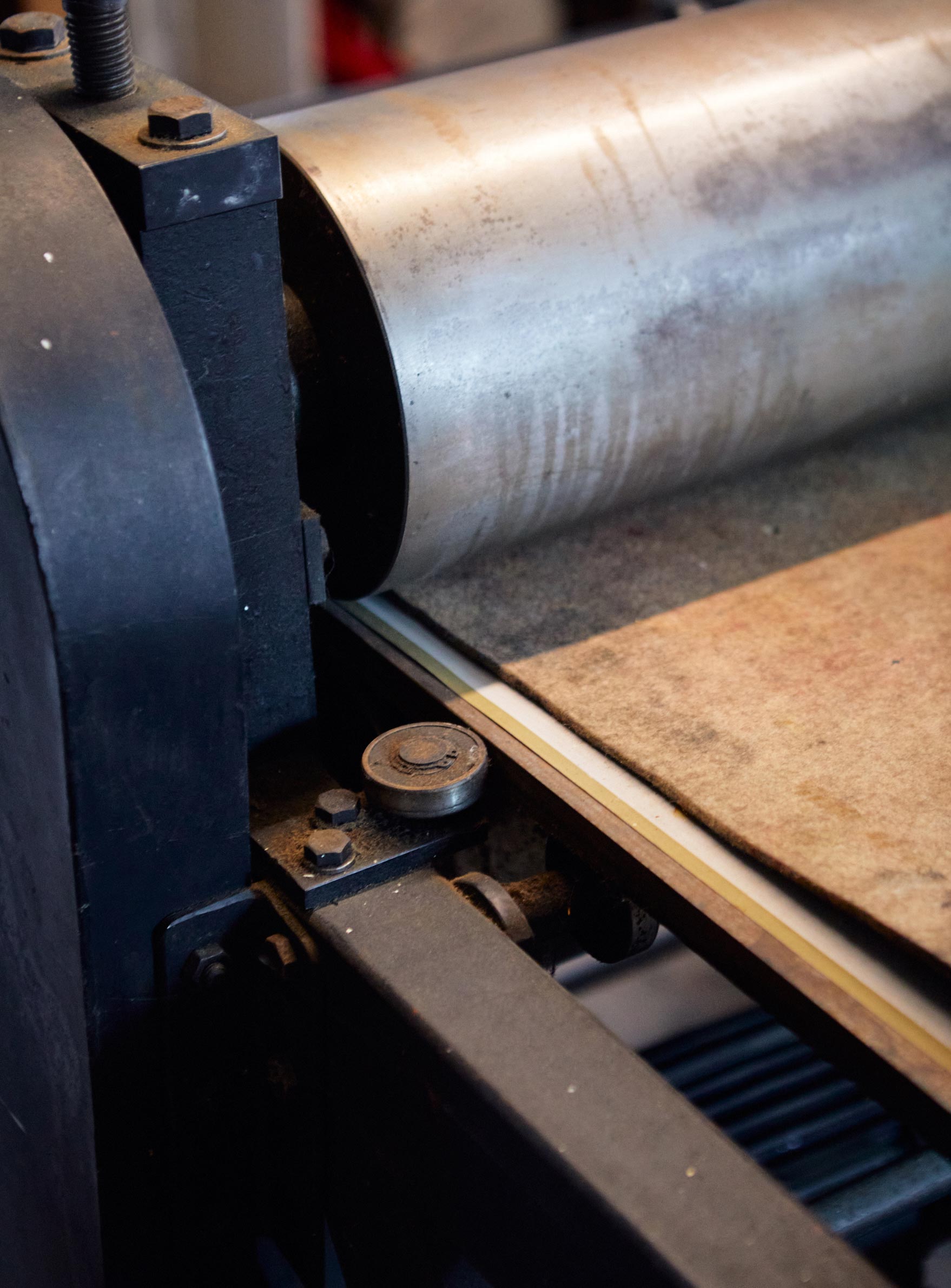

I will work on the story of my grandparents, to understand their influence on my personality. For this, I use the large gate of my grandfather’s locksmith shop for carving.

It looks very archaic!

Absolutely! The show I called Lost in Transmission, because transmission is what makes the locksmith work. Transmission for me is the element of propulsion, of going from one generation to the next, of passing down things. While working on it, I have come across very strong women in my family, and I wanted to erect a monument to them.

Exhibition: AONGHUS, 2024, Gut Kerkow, in cooperation with PSM, Germany, Credit: privat

Exhibition: AONGHUS, 2024, Gut Kerkow, in cooperation with PSM, Germany, Credit: privat

Exhibition: AONGHUS, 2024, Gut Kerkow, in cooperation with PSM, Germany, Credit: privat

Exhibition: Moser In A Mostshell, 2024, Gmunden, Austria, Galerie 422/Frames, Credit: Karin Hackl

Text: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Tim Zoidl