Naked breakfasts, coffee and cigarettes, a languid awakening, and crumpled beds — American artist Logan T. Sibrel explores intimate moments, predominantly of men, inviting viewers to observe. No risk of eye contact, as his subjects often look away, blurred or cropped. Between this closeness to private lives and the simultaneous alienation, Sibrel wants to give viewers a chance to project their own experiences.

Since we’re meeting the day before you leave for Greece for your exhibition, I’m curious—do you usually tend to finish your pieces well ahead of time, or do you often end up finishing everything just before the opening?

Usually, I am pretty good about doing things far in advance. When I know an exhibition is coming up, I tend to set a deadline in my head—often about two months earlier than the actual one.

Could you tell us more about this exhibition?

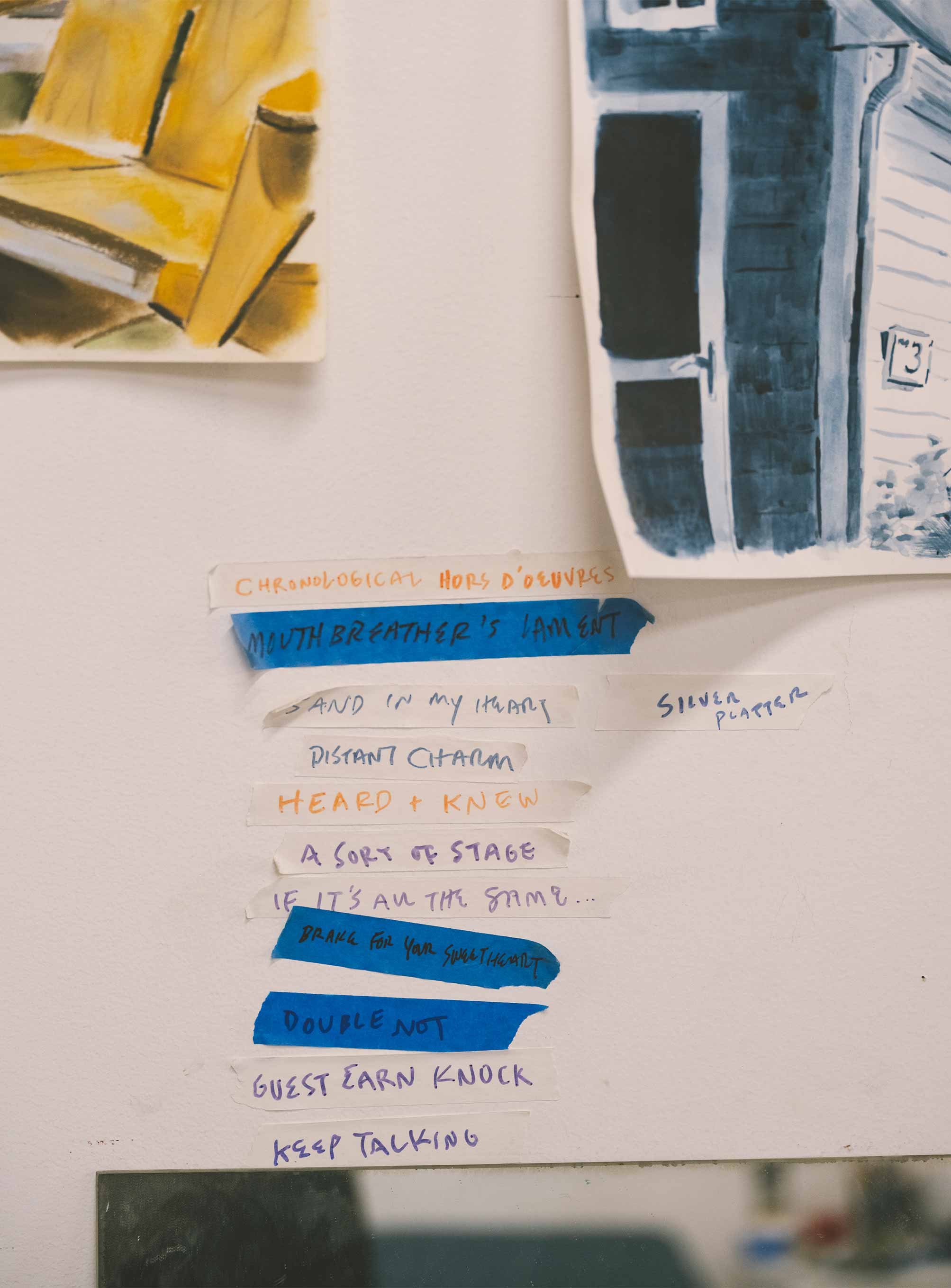

The exhibition at Eleftheria Tseliou Gallery in Athens is called “SILVER PLATTER”. It’s my first time showing there and my first time in Athens. There’s quite a bit of still-life in the show, but it’s treating still-life almost as a portrait. There are also figurative works, but somehow the still-life images seem more imbued with personality. The objects become a sort of a collage of a person, whereas the works featuring figures treat the figure more as an object. It’s kind of flipping the two.

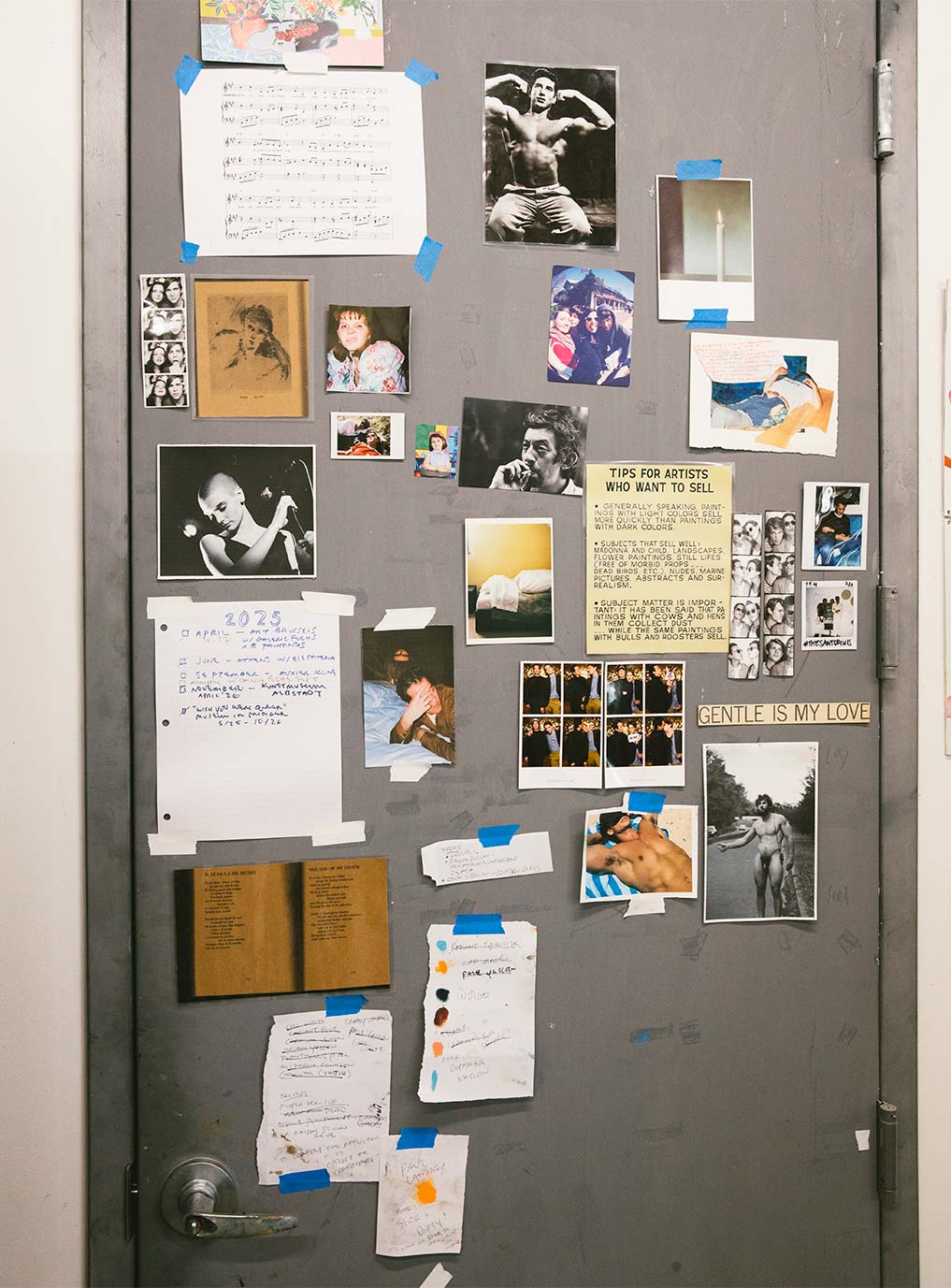

At the same time, your works are currently featured in two shared exhibitions—“Hot Spell” at Auxier Kline where you reside in New York City, but also “Wish You Were Queer” at the Museum im Prediger in Schwäbisch Gmünd in Germany. What is the background to your many German exhibitions?

I started showing more in Germany at the beginning because I have a very dear old friend, Nils Reinke-Dieker, who was actually an exchange student at my high school and ended up becoming a talented graphic and exhibition designer. We’ve collaborated for several years now, first at MOM Art Space in Hamburg, which helped get things rolling over there. I think, especially in Germany, there’s a kind of connection to the type of figuration I do—maybe because some of my early influences were German Expressionist painters. So there might be some subconscious link or shared sensibility. I’ve been showing with Galerie Thomas Fuchs in Stuttgart and with Auxier Kline in New York for about five years. It’s funny because I’ve been here in New York for 16 years, but it’s only in the last few years that I’ve started exhibiting more on my home turf.

How did your journey with Art begin?

I come from a small town in Southern Indiana, and I tell my friends I don’t get bored because of how I grew up. It’s a place with few obvious forms of entertainment. I mostly spent time in nature or drawing, and that was pretty much all I did. I think it’s important to find what you’re known for from a young age, and I was always known as the kid who would draw. I came out quite young, but I was able to draw and the novelty of that seemed to always offset any trouble I might have otherwise had — it was like, “Well, he’s gay, but he can draw.” I loved drawing, but it also became a way to have an identity. It was like my armour.

Was your family supportive?

Everyone in my family was always impressed by my drawing and painting. They were very supportive—maybe they didn’t always know how to foster it, but they’d do anything they could. If I needed art supplies, they’d always say, “Yeah, go for it!” They never stood in my way, so I had enough freedom and no pressure. They also, strangely, never suggested I find a backup career path.

You have mentioned before that growing up Catholic had a big influence on you artistically and that you can tell which other artists have the same experience?

Being Catholic, that was really my first exposure to a lot of physical art because there wasn’t much of a culture around it outside of that religious context. We’d go to church every weekend, and I’d just sit there and stare at the paintings. I was memorizing the narrative arc, all those Stations of the Cross, looking at the stained glass windows, and all that. When I say you can always spot a fellow Catholic, I mean there’s an aesthetic you absorb, sure, it is basically just Art History. But there’s a certain compositional and narrative structure that’s pretty unmistakable. I even notice that many of my painter friends who grew up Catholic tend to hang things in this almost triptych style, the works are pretty centered and frontal, and a little dramatic. I always pick up on it.

When did the queer narrative first appear in your art practice?

I had always been making work throughout high school, but it was more just for the sake of doing something. There wasn’t really a clear through line. Early on in college, I got into the Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) program at Indiana University where they treated us like master’s students, and I think that’s when I started noticing that everyone’s work seemed serious and cohesive. Being in that environment, I started playing with how I might go about that myself, and it just came naturally. My work has always incorporated my actual life, more or less. So the queer aspect came in because that’s just part of who I am.

In your paintings, there are personal depictions of you, your partner, and your friends. However, the identities are usually hard to discern, as the faces are frequently blurred, cropped, or incomplete. How did you arrive at this artistic technique?

I think that if I’m showing work to others and want to be in dialogue with them, I need to create a way in. Obscuring the figures allows the work to remain very personal for me, capturing something I find significant, but I’m not insisting that the viewer to have that exact same experience. When I make the paintings a bit more anonymous or obscured, it allows the viewer to project themselves onto it a little more. So it’s selfish and courteous at the same time.

How do your loved ones react to your artwork that may feature them?

I’ve had mixed reactions. I find it interesting because I feel like I do have this conversation with people–when I start getting to know someone, I can ask, “Is it okay if you’re in this?” It’s probably going to happen if we’re around each other enough. I remember the first show I had at Galerie Thomas Fuchs, where my partner saw himself on almost every wall for the first time. It was a bit of a strange experience for him at first. But when I make works of people I know, it’s never a cruel representation. I paint them because I adore them and find them interesting, so I think it’s pretty tender. I hope so, anyway.

It’s funny because there’s this back-and-forth relationship where a painting can seem really personal or very intimate to a viewer. But sometimes I just need a model — it’s not about us or about them specifically. It’s just a person, which is what I need, so it’s literally them, but conceptually, not.

I guess a big part of your research for your artwork involves observing and, in a way, voyeurism. What does that process look like?

I try to change up how I source my imagery. For a long time, I was pulling images from social media, being kind of an Instagram stalker. Lately, I’ve been working mainly from my own photos—taking pictures when something strikes me and trying to be a bit more passive in how I collect reference imagery. I just take a bunch of images and trust that something will work from them. I’m trying not to be so deliberate; I don’t want to orchestrate anything. I want to just let it come. I’m really aware of how I work and of my artistic niche. On one hand, I feel so present and in the moment because I’m paying attention to every little detail, seeing potential in it all. On the other hand, you’re never fully present because you’re always on the hunt for something. It’s an interesting point of tension, working from there.

Your works often include “images within images” such as photos, magazine or book covers, phone or laptop screens. What role do these inserts play?

Previously, I had worked for many years with collages. Literally constructing a map that would become the painting. At a certain point, I felt that this became a trap—really formulaic and kind of boring. Once you’re able to spot your go-to moves, it becomes a bit dull. I guess including images such as record and book covers in my works is a way of still making a collage, having multiple picture planes, but in real space. It can serve as a nod or a point of conversation. If there’s a particular writer tucked away in the background, it can point the painting in a different direction. Sometimes it’s just a still-life, but with Marquis de Sade (French writer and philosopher) in the background, which adds a layer of meaning or a bit of a twist. I guess it’s a way of allowing the paintings to go in multiple directions and see where it falls with the viewer.

What do you think when you see your work not quite where it was created for and, for example, being shared on the internet and social media?

When you’re making something –sure, you usually have an idea in your mind about the ideal viewing scenario or the ideal viewer. At the same time, I joke with my friends that I’m kind of a ‘reptile mom’— I’m mostly concerned about it while I’m making it. I have to just turn it off when I’ve done my job. As I get older, I feel it’s the easiest way to keep making it and not get too attached to an individual piece. I’ve made thousands of works at this point. It’s a way of having a really good relationship with a work while I’m making it. Whatever happens with it after it’s made, I have an image of it, a memory of making it. I have all the research that went into the images. I have my experience of what it means and what it was for me. And that’s all that’s really mine.

Correct me if I am wrong but your works became more colourful in the last few years.

I think it got a little more colourful because I was finally able to afford more materials (laughs). I did the book But I’m Different in Germany in 2022, and during that process, when I saw all the images and thumbnails, I had a panic moment—because it was the first time I saw it from this kind of aerial view, and I thought, “All the colours look the same.” With colours, it works the same as I mentioned about collages: if you use something long enough, it reaches a point where it’s like, “Okay, I could do this with my eyes closed.” So sometimes, introducing a new colour that might contaminate things in a strange way is just a nice problem to invent for yourself. A little assignment.

What else do you want to try in the near future?

Typically, I work with small to medium-sized surfaces, but my current assignment is to create enormous paintings while treating them like small ones. So, the composition remains the same as I would do for “a little guy.”

Maybe, it could be a nice format for a church?

Yes, it’s an altar potentially (laughs).

You often include lines from songs in your paintings, and the titles of your works also reference specific musical compositions. What role does music play in your art?

Music is a huge part of my life. Growing up, music was always an art form that was really present, so it was an early influence for me. Now, I’m a huge record collector—when I travel, I always grab things from used or 99 cent bins from different cities because what’s available is so specific to a location. I’m always listening to music while I work, and I am aware of how different types of music or artists can affect what I’m doing. Sometimes, I call it a cardio day—you just need to work through things really quickly, so I have a certain soundtrack for that. Other times, I want to be more thoughtful, so that has a different soundtrack. The majority of my show titles and the titles of individual works come from some song I was listening to while I was working.

I know you also have your own band called Sister Pact. Does it intersect with your art practice, or is it a completely separate medium?

It’s a place where I can put ideas that maybe don’t quite fit into the body of work of painting, but are still relevant or I just don’t want to let go of. I’ve had Sister Pact since 2014 with my friend Omar Afzaal. We had a rule that we would only play where we were invited, so as you can imagine, we haven’t played live very much. But that’s ongoing, and I’ve been working on a few things recently– here and there. I like it because, with my Visual Art practice, there’s a set schedule and upcoming shows, so you have to be very regimented. The music side is nice because there’s zero pressure, no deadlines. It’s kind of adjacent to what I’m doing but it’s just for fun.

Does your Art help you find answers about yourself, or does it only create more questions?

I’m of the mindset that when I go to art, music, or literature, I want to get more confused. I don’t go to it for clarity. The visual artwork I like is never didactic in any way; it’s not teaching a lesson. I’m really turned off by artists who try to do that. A lot of my work obviously comes from my own life—there’s a certain amount of self-reflection and self-awareness that you can get from that approach. But I don’t think I’ve ever actually gotten any answers from it or resolved anything. Sometimes, I look at images or work from five or ten years ago, and I think, “That’s what it was—that makes sense!” But I don’t think it’s ever served me at the moment. A real problem I see, culturally, is that everyone thinks they have the answer, and everyone’s so certain about their opinion on everything. I think it’s actually smarter and cooler to say, “I don’t know,” and to look at more stuff and complicate it all further.

Text: Anton Isiukov

Photos: Katharina Poblotzki