The scene for contemporary art in Europe’s North is expanding and developing new dynamics as international collectors are watching the scene. With Nordic Notes we regularly cast the eye on the Nordic art and cultural scene, portraying its important actors.

Inspired by science fiction and animal survival strategies, Congolese-Norwegian artist Sandra Mujinga explores themes of visibility and surveillance. She builds her own speculative space with ghosts from colonial history that she ties to difficult and sometimes uncomfortable questions pertaining to today. But Mujinga is not looking for an easy way out.

Sandra, you have been doing art for more than ten years with a multidisciplinary practice including sculpture, video, installation, textile, and music. How did it all start?

I didn’t really know that being an artist could be a thing for me. My mother worked with fashion and taught me how to sew at a very young age and encouraged me to draw. That’s why I was very creative as a kid. But it was always tied to practicality. When I saw the Lion King for the first time, I was really thinking that I will make cartoons or later on, work with fashion, or architecture or even graphic design. But it never came to art until the moment when a teacher suggested I should apply to the art academy.

What was your art like before and how would you describe what you do now?

A red thread in my art from 2012 to now is invisible bodies, or invisible presence. It was tied to working with language around loss, because I lost my parents when I was 15 and 17 years old. It affected the way I thought about bodies that were not there. That made me work with the idea of ghosts. Thinking about this invisible presence was connected to making music. The electronic sound was an entry point to the senses such as hearing as a way of thinking about bodies that you could not see. And then of course, my personal experience has influenced my art, with skin being an obvious theme. As a dark-skinned black woman, you will be aware of the certain way the world regards you from a young age. In more recent times, I have been considering decolonial practices and thinking about decolonization as a ghost, or as history that has been thrust upon the present time.

Speaking about ghosts. The large textile sculptures, posing as hooded, shadowy figures, are one of your signature works. And last year they were part of the Venice Biennale. What’s the idea behind them?

I was drawn to dinosaurs and thinking of them as our ancestors and how we discover them and find parts of their bodies. You don’t really know how the body looks, but then you build from what you have. So, I wanted to think about some stretched bodies from the past through a speculative lens, but also reaching into the future. I was working with shredded fabrics, old and new. My idea was thinking of a skin that was building up, but also simultaneously decaying. So, it’s very much drawn to that sort of in between state of the skin in two parallel timelines. Something is moving towards the future yet is also moving towards the past.

Some of your art has been perceived as intimidating on social media. What would you say to the audience?

It’s fine that some people find it intimidating. My art definitely contains some element of horror. I’m drawn to questions like what is the monster, who is the monster and what is it created for? And it very much stems from postcolonial theories of the process of dehumanizing people. The monster has this functionality. The audience although bring their own life experience and what they project onto the bodies. And the ghost figures can be threatening and powerful but also something that can guide us.

Is there anything that scares you?

Yes, I am actually very scared of snakes. There’s something about their movements I can’t understand. I’ve read that you can place a snake in a sock, and it will still move. It terrifies me.

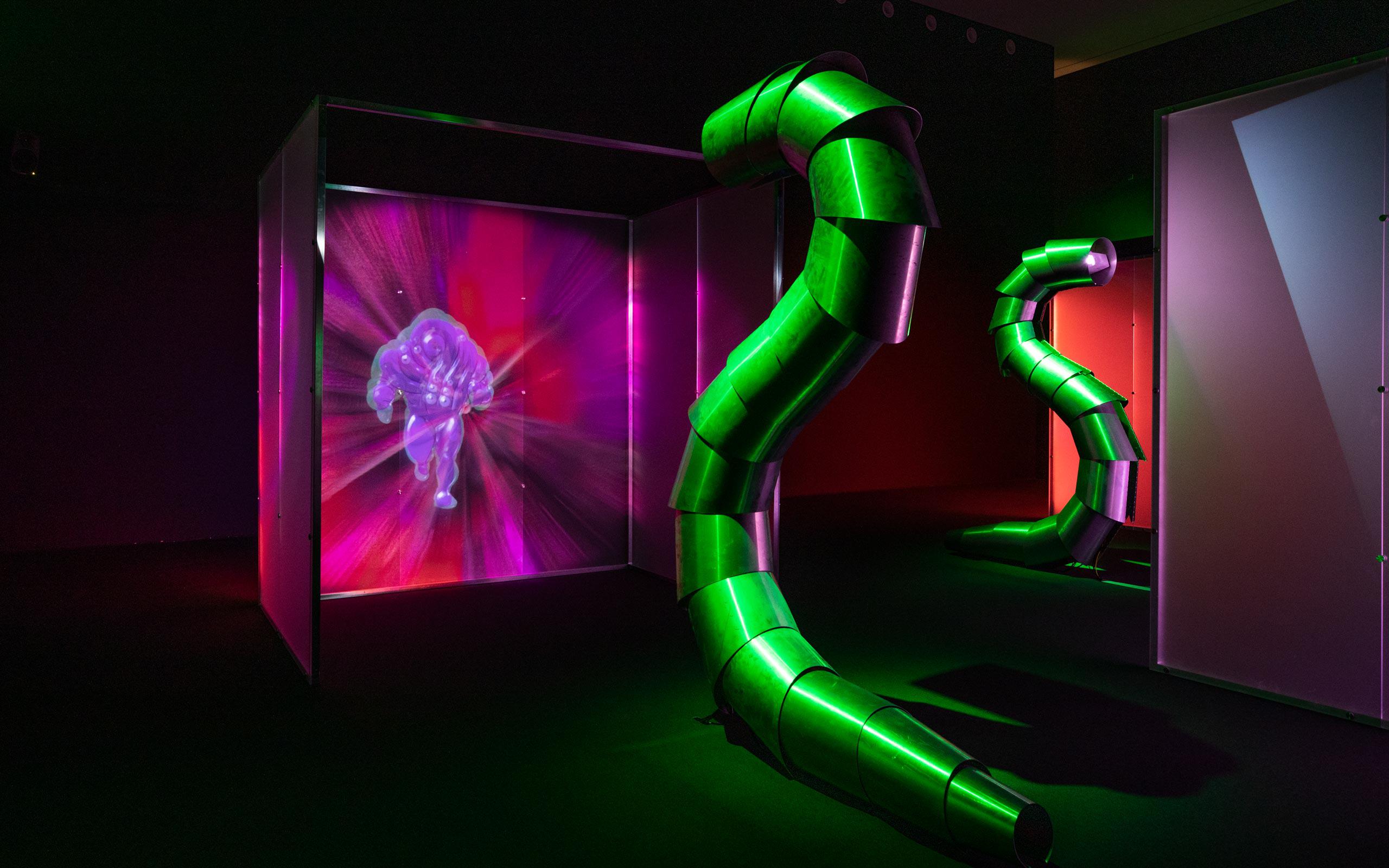

Your solo show in the winter of 2023 in Hamburger Bahnhof in Berlin is an homage to the French poet Edouard Glissant. A large black box covered with a 9x4m LED video display that envelopes it like a skin occupies a space between the ceiling and the floor. In what way is it connected to Glissant?

The titles of my last couple of works have been an homage to Glissant. I called my exhibition I Build My Skin with Rocks, while Glissant used I Build My Language with Rocks. For him, language is separated through rocks, while for me, the skin is becoming firmer. I’m building a shield with the rocks. With this piece, I was thinking about size as well. Size here is something really abstract, because the body can’t be measured. A body with no borders is seen as a threat, as bodies on the move are continuously policed, here also thinking about politics around migration and borders. You can see the body through an ultrazoom, which can be seen as my take on extreme surveillance. At the same time I see the body becoming a landscape and disappearing in the dark. It becomes a body that cannot be contained. That’s why it can also go unnoticed.

How did you create the look for the performer in the video?

I was working with prosthetics, which is kind of outdated, so again I went back to using elements of the past for the future. Especially in films there are often digital manipulations of the face. In this case I built a face with a mask and created an elephantine-human face. For the installation I had to measure in space. Because you can’t measure the architecture, people walking by it would appear smaller. So, it’s about us measuring other bodies in this space too.

You have mentioned both elephants and dinosaurs. In your manifesto at the Munch Museum, you tell us about your connection to whales. I saw your social media stories with the actress Jennifer Coolidge who said she is dreaming of playing a dolphin. Are you drawn to marine animals as well?

I’ve been fascinated by the deep sea and the idea of how deep a whale can swim. It appears on the surface, and then it dives. For me, the deep sea has been this speculative space, where it hosts darkness, where different creatures exist and operate. I’ve used the deep sea as a way to be inspired in my own world building, when I create characters and think about a new body. I’m drawn to these kinds of bodies that are quite intimidating, but you don’t really know how they would move. They don’t choose to be intimidating, or violent, but they can swipe you off because they have this force. As a DJ and producer, I also think about the sounds whales make. I think it’s quite powerful how sound exists on these levels and has even been used in warfare. But it can also be used to calm you down.

You were born in The Democratic Republic of the Congo, and grew up in Norway, and are now also working in Germany. How do you think all of these places have influenced you?

I have this experience of moving with my family that has taught me not to panic over new existence in a new space. When I grew up in Norway there was a restlessness within me. When I was later accepted at an art academy in Sweden, I thought it was an opportunity to get out and create myself in a way that was not expected of me. All these places have given me opportunities to continue to reinvent myself and try out new things rather than always existing in the same patterns that are already projected onto me.

Previously you have said that you are thinking with your hands. What do you mean?

I have to do things, so it’s about being in a dialogue with the material. There’s friction, and it’s also messy, and accidental. But it’s also a process of listening.

What is it that you are listening to?

When I build a show, I like to make 100 versions of things. For the exhibition at Hamburger Bahnhof for instance I made different skins and renderings. I also need to have space to listen and to be with the material and the sculpture. That’s what I find beautiful about having a studio, that I can make something and then look at it and be with it for a longer period of time.

You will be featured at MoMA and will have a residency in New York later in 2023. But looking back first, what are your takeaways of your past to this date?

I think the truly biggest gift is that there is only one you. It sounds like a cliché, but it’s about creating that space to know yourself honestly and fully, in order to also treat yourself with integrity and kindness, and to treat the world in the same way. This has not been an easy process. What I have learned with art is that things are difficult. But it’s a good thing when questions and discussions are difficult. Everything can’t be solved instantly. Existing in these situations is nurturing, because that’s also when things are happening.

Sentinels of Change and Reworlding Remains, 2021, Three sculptures: Woven torn second-hand fabric, bedsheets, curtains, linen, cotton, organic cotton, dyed cotton with textile dye and acrylic paint, cotton coated with concrete, sound foam, soft PVC, steel rods with caps for tubular steel (felt and plastic), concrete base with foam, 270 × 100 × 35 cm; One sculpture: Waxed MDF, steel rod and plate, cotton 800 × 300 × 200 cm, Courtesy the artist, Croy Nielsen, Vienna and The Approach, London

Spectral Keepers, 2020, Tulle fabric, cotton fabric, nylon thread, threaded rods, wire clamps, cellular concrete. Figure: 278 x 80 x 40 cm, basket: 77 x 77 x 97 cm, Mítáno,

Tulle fabric, cotton fabric, nylon thread, threaded rods, wire clamps, cellular concrete. Figure: 278 x 80 x 40 cm, basket: 75 x 80 x 102 cm, Mínei, Tulle fabric, cotton fabric, nylon thread, threaded rods, wire clamps, cellular concrete. Figure: 284 x 80 x 40 cm, basket: 85 x 78 x 102 cm, Míbalé, Tulle fabric, cotton fabric, nylon thread, threaded rods, wire clamps, cellular concrete. Figure: 282 x 80 x 40 cmbasket: 70 x 82 x 96 cm, Private collection Photo: The Approach Gallery

Closed Space, Open World, 2022, Three-channel video installation with sound, Consisting of 3 x aluminum sculptures with projectors inside and led-strip light. Estimated size each, 150cm (D) x ca.3 m (H). Three clear frosted plexiglass boxes, 2x (H:3000mmx L:3024mm x D: 2002mm) 1x (H:3000mmx L:4026mm x D: 2002mm), glass clamps, carpet, walls painted black and green light. Animation drawn by: Nancy Saphira. Three different files, 10 minutes asynchronised loops. Courtesy the artist, Croy Nielsen, Vienna and The Approach, London. Photo: Ove Kvavik

Interview: Anton Isiukov

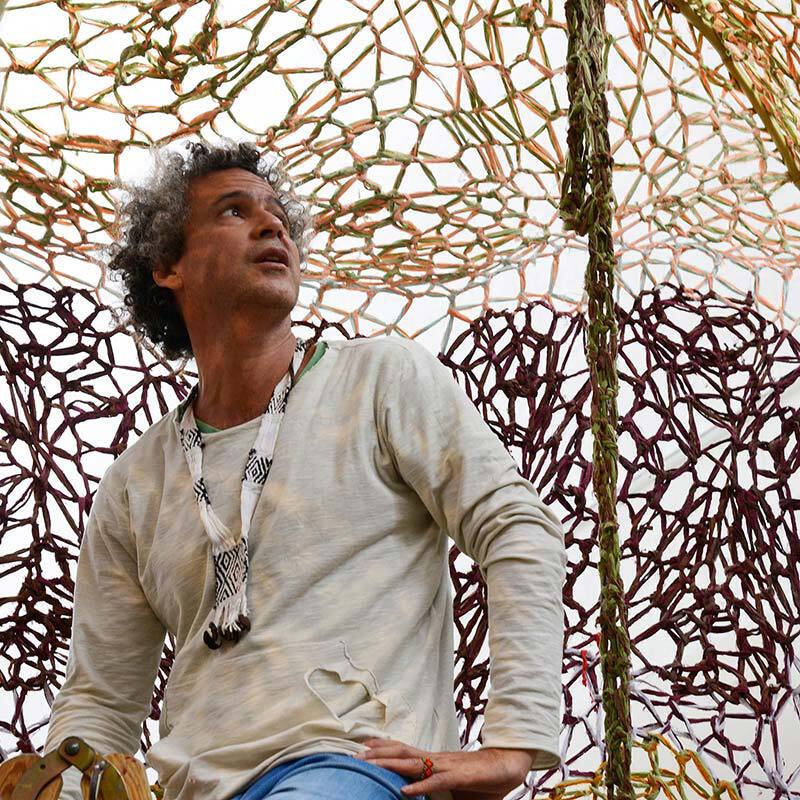

Photos: Signe Fuglesteg Luksengard