Tillman Kaiser’s language of form is characterized by symmetrical compositions and reduced color. His interest in the rhythmical element in music is felt equally in both his photographs complemented with painting and collage and his utopian sculptures.

You studied at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna with Hundertwasser and Schmalix. In Vienna, Hundertwasser is virtually part of the city’s cultural identity. What influence did Hundertwasser have on you in this early time in your artistic development?

Hundertwasser is very controversial, many of his buildings are questionable. Unfortunately, he allowed himself to become commercialized – not for monetary gain, but through his concern for environmental protection and his vision of the connection between man and nature. Although Hundertwasser was an extremely good painter, I wasn’t really concerned about under whom I studied. I met him only two or three times, he said that one cannot teach art and that students are attracted to the academy like bees to nectar of dubious quality. He certainly had an excellent assistant, the photographer Peter Dressler, Dressler’s approach to teaching viewed artists as human beings.

How did you come to art and when did you decide to become an artist?

I have always drawn. By the time I reached puberty I had begun to draw and paint intensively. For the most part it was a kind of self-therapy. It was the best way for me to express myself. At the academy I noticed that the self-therapeutic works were insufficient. This was because I had no distance between my work and myself. Greater substance is obtained when there is distance between one’s artistic practice and one can contextualize oneself in a plausible way with society. During my years at the academy I made a difficult choice and began to paint houses instead of abstract forms. Eventually, I noticed that I had moved away too far from myself and, over time, I succeeded in combining the chaos of the subconscious and clear thoughts, forms, and ornamentation, and to develop my own methodology and visual vocabulary.

Did your surroundings influence your early artistic career? Can you name any artists whose work you found groundbreaking?

At the academy we moved in a very inspiring atmosphere, but I wasn’t really taught - and I think that art can only be taught to a very limited extent, but one can give the student guidance towards self-knowledge. I don’t know how it is these days at academies but, personally, I basically learned nothing while I was there. However, I don’t believe that was a problem because I had the opportunity to develop freely. After my studies I worked in a big Viennese gallery in exhibition installation and trade fair installation. That was very exciting for me because it gave me the opportunity to see a lot of good art. Imagine, in the Academy we never went to a gallery or visited an exhibition!

I have always been very interested in Surrealism, it appeals to my inclination toward reflection. One may not recognize it in my work, but I have a great appreciation of the work of Giorgio de Chirico and of René Magritte.

Most of the time you listen to music when you work in your studio. Does that have an impact on your artistic creation?

Music doesn’t influence my work directly, but its essence most likely enters my work. My picture compositions are often based on repetitive elements, translated into music they would be extremely rhythmical songs. Rhythm cannot only be found in music but also in the fine arts, literature, and poetry. Rhythm is very important. I am interested in the psychological effects that repetition can trigger.

Although you are in the center of the city in your small studio in a former tobacco store, you are actually quite isolated. How do you feel about that?

On the way to my studio I sometimes imagine that every step on the way leads into a deep cellar. Having arrived there, I am out of reach and hidden.

So far, what has been the greatest challenge in your artistic career?

The greatest challenge is always the beginning of a new work, and it never becomes easier. Challenges are part of life: it is a big challenge to manage profession and family. One always has more projects on one’s mind than one can realize. Sometimes I wish there would be several Tillmans who could work in parallel, one producing paintings, one building sculptures, and a third finding new ideas.

Every new work I begin challenges me to be aware of not repeating myself. I certainly have my routines, but routines can be dangerous. If someone refers to himself or herself as a professional artist, this triggers an alarm for me; because in my opinion professionalism and art are a contradiction. To me a professional is someone who does something extremely well and approaches it with a precision that requires an adherence to routines. But as an artist, one should not adhere to one thing, but should always be looking for a new approach, at least successively. If I did not do this, I would be a complete charlatan.

Have you ever considered ending your artistic profession?

No, never! It is a difficult occupation yet at the same time it is the most wonderful I can imagine. Each day one can do what one wants and nobody issues instructions, inevitably it requires a good deal of self-discipline.

As an artist, one has chosen a hard path. I notice with colleagues with whom I have studied, that most are obliged to pursue something additional in order to support themselves. In our society, only remunerable work is considered of value and valued is he who earns money. Yet there are many groups of people who achieve much with little remuneration and often with sparse acknowledgement, single mothers are an example.

As an artist one has a degree of social freedom and it may be considered that contingent upon such freedom a certain sense of responsibility is required. Do you recognize a sense of responsibility in yourself as an artist or indeed towards art in general?

I think that as an artist one lives on the fringes of society, as an outsider so to speak. This can actually be viewed as an advantage as it offers the possibility of observing the world from a quite different perspective.

What aspect of artistic creation in artistic creation is most essential in your opinion?

It is absolutely essential to stay authentic in one’s work and to question it at all times. I think as soon as one begins to lie to oneself, viewers notice it immediately.

With regard to your objects you’ve said that like a science fiction director you want to amaze people and therefore work with psychological tricks. What should we expect?

That was such a long time ago that it is now an old story. I meant that I find it interesting to take things out of their original context and align them with a new one – perhaps in collage form.

Do you begin your work with an idea, a specific thought, or does the concept develop in the sense of an abstraction drawn from the subconscious during the work process?

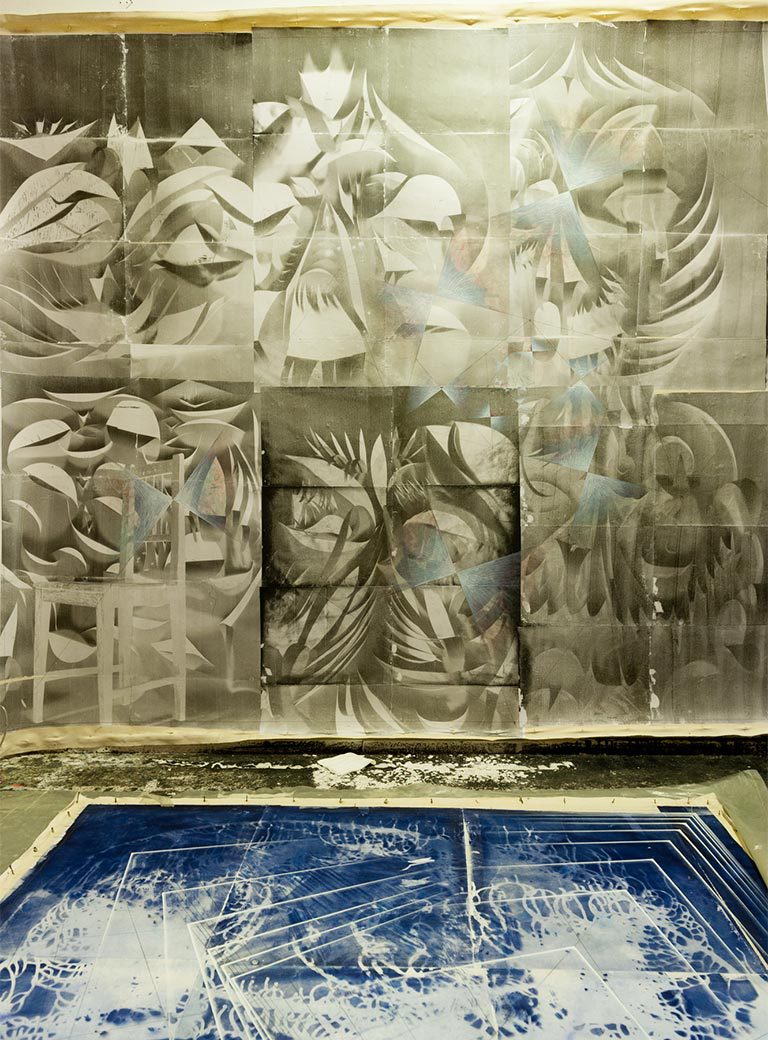

One certainly has many ideas during the work process which flow directly into the work, but I prepare the works with the help of sketches and spatial concepts, and also, in my case – kneeling on the floor and painting.

How much explanation does your art need or do you want the viewer to address it intuitively?

I find it very good when works function without explanation. But I also like to provide an explanation if it helps. I also respect art that does not function without explanation. The fantastic thing in art is that everything is allowed – as long as it is well made. There are no dogmas as in religion. If for example someone thinks painting is obsolete, this falls for me under unnecessary dogmatism. Basically I find it very exciting, when viewers have their own associations and the works function on the basis of reflection.

In its reception your work is seen as under the influence of various art historical styles: Cubism, Futurism, Surrealism, Bauhaus, Postmodernism… Is there something of a misunderstanding in the perception of your work that you would like to clarify?

Utopias and dystopias can be very interesting, but their significance tends to be inflated, I don’t place too much importance on them. As far as viewers are concerned, the perception of an artistic position is largely dependent on current trends and fads.

Some of your objects such as Moontrap or Table are reminiscent of the children’s origami style paper folding game ‘fortune teller’. Would you say you play with the viewer’s perceptions?

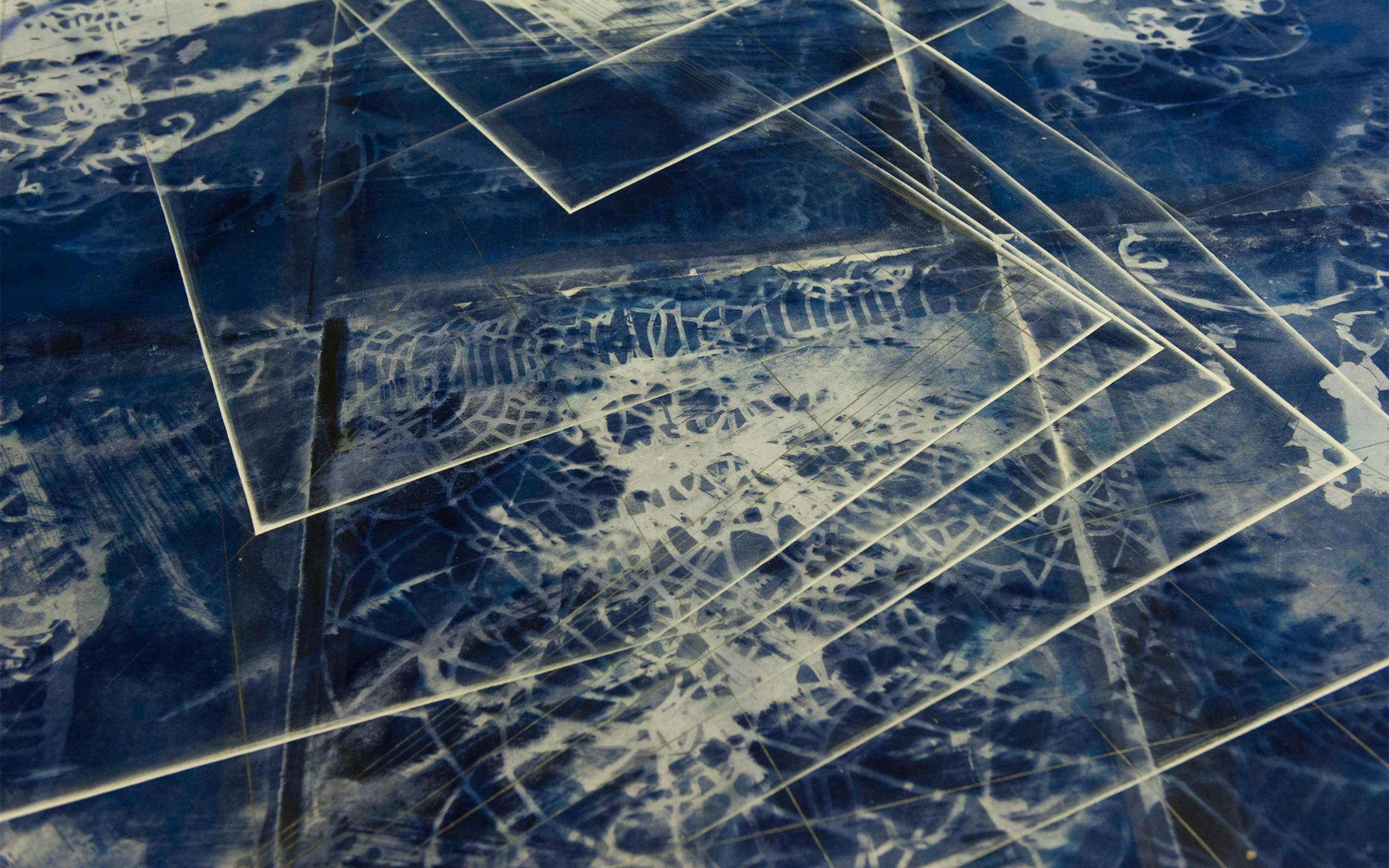

I am interested in symmetries, there is an element of rhythm where there is no above and below, no back and no front resulting in forms that resemble the folded paper game. I also find it interesting that when drawings are placed on top of each other rhythmic shifts result in a similar way to syncopation in music: One beat is omitted and the other is doubled. Such overlays are very beautiful; I try to realize this in my works.

How did you arrive at the photographic techniques?

The photographic images are not planned; they developed in the course of time. I like this development and I find it interesting because I am originally a painter. My art developed from painting to collage, in an earlier phase I worked a lot with screen-printing, always complemented with painting. When I had exhausted this technique, I turned to photogrammetry, in the form of cyanotype, an old photographic printing process by which the typical cyan-blue prints are produced in the darkroom by mixing two chemicals, [ferric ammonium citrate and potassium ferricyanide] which are diluted with water, a procedure by which they become light active. I then apply the photosensitive solution to paper after which it can be exposed to sunlight. The result is a photogram, which differs from a conventional photograph in that it has been produced with direct light exposure but without the use of a lens. I also make black and white photograms using a silver gelatin solution.

Later I built a camera obscura, an early stage in the history of photography in which unlike with the photogram, no direct exposure onto light sensitive material takes place, unless of course, one chooses to do so.

Where do you see your sculptures in regard to this process, where do they stand? Have they always existed?

I started building sculptures when I began painting architecture. At the time I copied houses in the form of models constructed of cardboard. Departing from these architectural models the spatial work procedure became abstract and a force unto itself; over time, I began to integrate other things.

These objects, which you integrate into your sculptures, how do you find them and according to what criteria do you select them?

They are objects that have a certain aura or tell a story, like this chair here, which I found on the beach this summer – perhaps it will be integrated somewhere, or the interior of this thermos flask, whereas this doll’s head will not function, it is too explicit.

Is beauty in art a criterion for you? What distinguishes beauty in your eyes?

In my opinion reflecting on esthetics and beauty is important. I believe that people are in search of beauty. That is really universal. Like in the animal kingdom, in which birds are often beautiful because of their grandiose colors. One can reflect on art as one reflects on philosophy. The esthetic aspect is very important to me. The German author Herta Müller has said something on this subject, which I consider very true: Beauty is not just a medium of style or an ornament; beauty is substantial.

Is it your goal to create something that is beautiful?

Not in the sense of being appealing or nice, I want to create something that has depth. When you hear complex music you sometimes don’t really find it beautiful right away, at times you may not even be able to endure it. You have to listen to it repeatedly so that it can unfold. It is like learning a language. It is similar with my work.

The beauty of art is that it stands for itself and is not good for anything, it does not serve an immediate purpose, like a hammer or a cigarette lighter. Therefore, it cannot be replaced. Beauty is appreciated because of itself; that is beautiful.

Your works are very color reduced, mainly black and white. Why is that?

This is because the forms that I use are very strong. If they were at the same time colorful it would be too much in my view. But lately I have been missing color. Who knows what is still to come... Perhaps I’ll manage to become a bit more colorful. My hope is that I won’t stand still, but continue to develop further and further.

On what project are you presently working?

At the moment I am producing extra-large paintings for my exhibition in the Secession in the fall of 2019. I love large formats; one has more freedom with them. A mistake in a small picture is a catastrophe, but in a large picture it may be an enrichment.

Lately I have made fewer sculptures, because the paintings keep me very busy. I take photographs with the camera obscura and produce cyanotypes, these are very work-intensive procedures; however, I will go back to making sculptures.

Interview: Barbara Libert

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt