Austrian artist Daniel Hölzl works primarily with recycled materials such as paraffin wax, carbon fibre, and industrial fragments to create sculptural and installation-based works that make complex material and technological cycles visible. In his process-oriented practice, he explores the cyclical nature of resources, questions of transformation and impermanence, and the global systems into which these materials are embedded. His work opens up a reflection on temporality, use, and responsibility, inviting us to reconsider the stories and meanings of materials.

Daniel, you were born in Tyrol and studied in Berlin and London. What drew you there, and how did those places shape you artistically?

I moved to Berlin to study fine art. During which time, I spent about seven months in London on an Erasmus+ exchange. It was a great contrast: Berlin was much more free, open, and experimental, while London had a different kind of drive—everything was faster, more structured, but unfortunately much more expensive. That forced me to organise myself differently. I’d say what really shaped me was the mix: the freedom of Berlin alongside the London experience of having to stay focused if you want to move forward.

You chose art quite early on. What did your path look like before university?

I went to a great school in Austria—the HTL for Construction and Design in Innsbruck. I specialised in sculpture, and there were only ten of us in the class. It was like starting an art degree at fourteen. Out of forty hours a week, twenty-two were dedicated to studio work, art history, and so on—so really half the time was spent making art. After graduating, I worked for four years in Innsbruck as a stonemason and restorer for art and monuments. But I always wanted to do something of my own, so the next step was clear quite early.

Did you always want to be an artist?

It sounds a bit cheesy, but yes. I even have one of those old friendship books from when I was seven, in second year at school. For the question “What do you want to be?” I had scribbled, very on-brand: “Artist”.

Did your time as a restorer influence your artistic work?

Definitely—a lot, especially in terms of craft. At HTL I’d already worked with materials like stone, wood, ceramics, and metal. As a restorer, I could really apply and deepen that knowledge.

What did you take from that experience?

I still try to do as much as possible myself. I’m really interested in how materials behave—when something melts, becomes malleable, breaks. That closeness changes the work. Many of my pieces would have turned out very differently if I’d just outsourced them. Of course, for very large formats or heavy objects I love collaborating with others—it wouldn’t be possible otherwise. But for my practise it’s crucial that I work with the material myself—that I understand it, not just plan it.

Why did you choose Berlin in the end?

The options for studying fine art in Austria would have been Linz or Vienna, but I felt I needed to get away from the familiar. I only applied to two places: Berlin and Edinburgh—and luckily got into both. In the end it was Berlin. It wasn’t a long-planned decision, more of a gut feeling.

How would you describe your art in your own words?

My work is often site-specific, installation-based, and very varied. There’s no fixed style or medium I always use. What does recur is my interest in materials and their cycles. I’m fascinated by connections: how materials are used, transformed, recycled; the systems they circulate in; and the feelings we attach to them. The throughline is really conceptual: cyclical processes, change, time. It’s about the principle of transformation, not a fixed theme.

What exactly do you mean when you talk about a “cyclical material practice”?

Really, we’re only borrowing materials for a certain time. If you take stone from a mountain and carve it into a sculpture, that moment of admiration is fleeting, on a geological scale, before it eventually erodes back to sediment. And, of course, that sediment will one day become stone again. I find that idea compelling: that art, even if it seems made to last, is always just a temporary form in a larger cycle of material, time, and transformation. It raises interesting questions about resources, sustainability, and responsibility.

How does this cyclical approach to material show up in your practice?

Often it emerges directly from the work itself. In the exhibition GROUNDED, for example, there was a large wax sculpture made from old church candles—a life-sized cast of an aircraft tyre that melted over the course of the show. I’m now using those 300 kg of paraffin wax for new pieces, painting with the liquid wax onto fragments from that previous floor installation. I kept the material precisely because it’s about impermanence and transformation. Change happens before, during, and after each exhibition.

Is material “active” for you?

Absolutely—material is an active agent. That’s often exactly what I’m interested in: giving the material space to unfold. Sometimes that transformation happens in the studio, sometimes only in the exhibition, but there’s always that moment when the material co-creates the work. I set a framework—literally and metaphorically. For example, I’ll set parameters like the temperature of a hot plate. I can predict roughly what will happen, but exactly how the material reacts, flows, drips, or deforms is left open. That controlled “letting go” is important to me. The material brings something of its own, and that often becomes the most interesting part of the work.

What draws you to materials like paraffin or carbon?

I’m fascinated by the carbon cycle and petroleum itself because it’s everywhere in our globalised world. Paraffin wax was originally a byproduct of oil refining, though it’s now expensive and mainly used for candles. Industrially produced carbon fibre also derives from petroleum, made through sheets that are ‘burned’ in a vacuum. One becomes soft and liquid quickly—it releases its energy fast. The other is extremely stable and durable - carbon remains carbon indefinitely. That contrast really appeals to me: two materials with the same origin but completely different behaviours that end up merged in a single work.

How do you use these materials in your work?

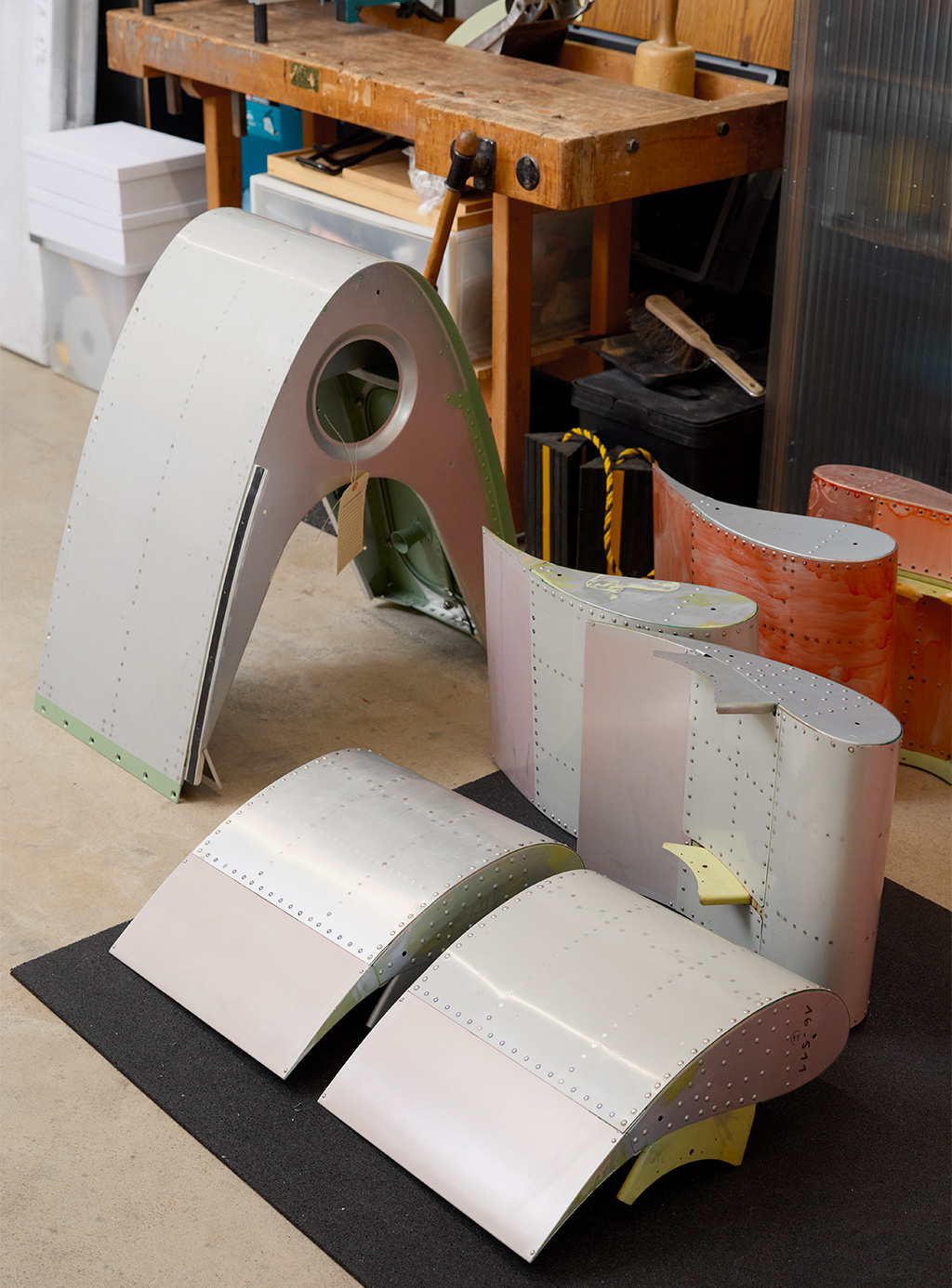

I often work with recycled paraffin—old candle remnants, for example, from churches. I consciously avoid buying new raw material and instead use what already exists. The wax is melted and layered onto old aircraft parts, or the nonwoven fabric made from them. Depending on how many layers you apply, the colour changes: 15 thin layers give you a neutral grey, 30 layers a solid white. I then also melt some of these layers back out of the fibres using a modified soldering iron. This technique has evolved over the years—it wasn’t something I planned from the start.

How much of your work is experiment, and how much is conceptually pre-planned?

A lot is carefully thought through beforehand—I usually have a clear conceptual reason for using certain materials. For example: why paint aircraft motifs with oil-based products on supports that also derive from oil? There’s a clear internal logic there. In GROUNDED, I only chose motifs where the aircraft is in contact with the ground. The material, in a way, returns to its origin. But the process itself was highly experimental at first. I had to learn, for example, exactly how hot the wax could be for painting—too hot and it instantly melts the layer below.

How do you see your work in relation to environmental issues like climate change or the Anthropocene?

Those themes are definitely present for me. I learn a lot about them—through working with certain materials. When I’m dealing with oil-based products, questions come up automatically: Where does this come from? How is it produced? What happens to it afterwards? That always involves research. I don’t use materials “just because”. Even with my inflatable works made of parachute silk or other fragments with specific local connections, I’m interested in the stories behind them and the systems they reflect.

So you also see your practice as a way of engaging with global structures?

If you “borrow” material from these highly charged, widespread systems, the question almost automatically arises: what exactly are we doing? How does globalisation work? How do entrenched systems burden the environment, and where are improvements already happening? These questions feed into my work—but I also learn about them as I go. And of course I hope that visitors to my exhibitions can sense these connections or even take them with them.

How do you deal with the contradictions—for example, that the art world itself is part of this machinery?

I’m very aware of that. Art needs resources; the art world is energy-intensive—from climate-controlled spaces to international transport. But I don’t think it’s about solving everything dogmatically. What’s important to me is to look closely, to ask questions—not whether something happens but how it happens. And to keep a sense of humour. It’s not only about the negative side but also about making connections tangible and exploring aesthetics. For me, it’s also about learning myself and creating moments of surprise or reflection.

Does art have to be political? Do you see that as part of your own work?

No, I don’t think it’s an obligation. But art can be very political because it can show things differently, pull you out of your everyday perspective into something unknown. You don’t have to explain everything, and yet a work can point in a certain direction. Of course, everything is a choice. I think the more people engage with art and culture—including knowing what they don’t like—the more they’re able to accept the world, and especially themselves and each other. And to me, that’s already deeply political.

You also work a lot in public space. What does that mean to you?

A lot. Public art reaches people who wouldn’t necessarily go to a museum or might not even realise you can just walk into a gallery. On the street or in a square you get very different feedback. Some people are puzzled, others delighted. That’s important: it sparks conversation. With Bycatch, the work I keep showing with Abie Franklin, this is especially clear. These walkable, inflatable wave breakers have been installed right in city centres, spanning rivers like bridges, forming small islands in Danish fjords or on Berlin’s Spree. You can’t control who experiences it. And that’s exactly the point.

What do you want visitors to take away from your work? Is there something especially important to you?

It’s important to me that a work leaves space—for people’s own thoughts, associations, moods. Everyone brings their own context, whether they see the piece in a museum, in a village square, or in someone’s living room. A work doesn’t have to explain itself completely, but it should offer enough that you want to dive deeper. I find it exciting when both are there: an aesthetic level and a conceptual foundation, without one outweighing the other.

So you want aesthetics and concept to balance?

Yes, they should at least complement each other. Sometimes the form comes first, sometimes the theme—it doesn’t matter. What’s important is that material, idea, and space interlock so you can sense there’s thought there, but also feeling. I do a lot of research, but I also leave space for the material to unfold.

How do you handle the fact that people interpret your work differently?

I find it incredibly enriching. I’ve heard lots of interpretations I’d never have thought of myself, but they still fit the work. Especially with more abstract forms, many layers can overlap. And of course it makes a difference what mood you’re in when you visit an exhibition. Some people see mortality in my work, others see hope or just an interesting surface. All of that can coexist.

Have you ever been surprised by someone’s reaction to your work?

Yes, many times—and I really value that, including misunderstandings. If someone sees something in a piece that I didn’t intend, it means in a way it’s in there. A good example is my series AFLOAT, made from boat parts and old fishing rods. I wanted to reverse the relationship of catching and being caught: the rods were built into the architecture, themselves captured instead of capturing. But then someone said it looked like a brushstroke on the wall—very graphic. Another person said it reminded them of a fish trap, which is spot on even though they didn’t realise they were bundled fishing rods. I hadn’t thought of that, but it really fits.

The fishing rod is a good example of the contrasts you work with, right?

It’s an ancient tool for getting food, very primal. But it’s also a sporting device, even something a bit romantic. I use pole rods—the oldest form of fishing rod but in its most modern, carbon-telescopic version. And in my work, boat parts are added, segments of railings that are meant to protect us, but when repurposed are suddenly read as spear tips or knuckle-dusters.

What can we expect from your upcoming projects?

In Berlin, my work soft cycles will still be on the roof of the museum Berlinische Galerie, while at the same time I’ll have my solo show PROPEL during Berlin Art Week at Dittrich & Schlechtriem—a kind of continuation of GROUNDED. I’ll be showing works that explore the early spirit of invention in aviation—found footage of experimental flying machines that never flew, but for me embody that pioneering spirit and euphoria. At the same time, I’m addressing failure: bent propellers, melting casts, images of wilting flowers—all these forms of collapse and new beginnings.

What interests you about that link between the past and future of flight?

Flight stands for freedom, mobility, progress—but also for war, destruction, environmental impact. I think it’s important to recognise how complex that is. Today, companies are working on making flight electric and more sustainable—which basically means bringing the propeller back. That “comeback” is a beautiful image - something old becomes a technology of the future! But of course, the question is: how sustainable is electric flight really, and what kind of systemic change does it require? That’s something I find exciting to explore. With one eye on the past and one on the future.

©Abie Franklin and Daniel Hölzl "BYCATCH" in Vejle, DK, 2023, foto: Ard Jongsma

©Daniel Hölzl "LIVE BAIT" at super bien! Berlin, DE, 2023, foto: Daniel Hölzl

©Daniel Hölzl "GROUNDED" at Dittrich & Schlechtriem, Berlin, DE, 2022, foto: Jens Ziehe

©Daniel Hölzl "soft cycles" at Berlinische Galerie, DE, 2025, foto: Clemens Poloczek

Text: Livia Klein

Photos: Patrick Desbrosses