Poetry resonates in Edin Zenun’s works as he gesturally applies muted colors onto canvases, producing works reminiscent of Karst landscapes. The use of self-mixed paint and self-built wooden frames gives the paintings of the young Macedonian artist an aura as if they had been around for much longer already. We met the artist in his cozy basement studio to talk about his art, his experiences as an exhibition organizer, and about the parallels between music and painting.

Edin, you studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Tell us about your career: How did you come to painting?

I came to Austria as a refugee from the former Yugoslavian province of Macedonia – now the Republic of North Macedonia, in 1992. I grew up in Styria and moved to Vienna in 1999. I was a rather quiet child and easily occupied, most directly with drawing and painting; even as a small child, I would spend many hours painting. To me this was always the most beautiful activity. There is this little rectangle in front of me and I can do just about anything with it, because of its finite dimension. I can create everything myself, it’s my own world.

Did you prefer to work on an almost square, small format when you were a kid?

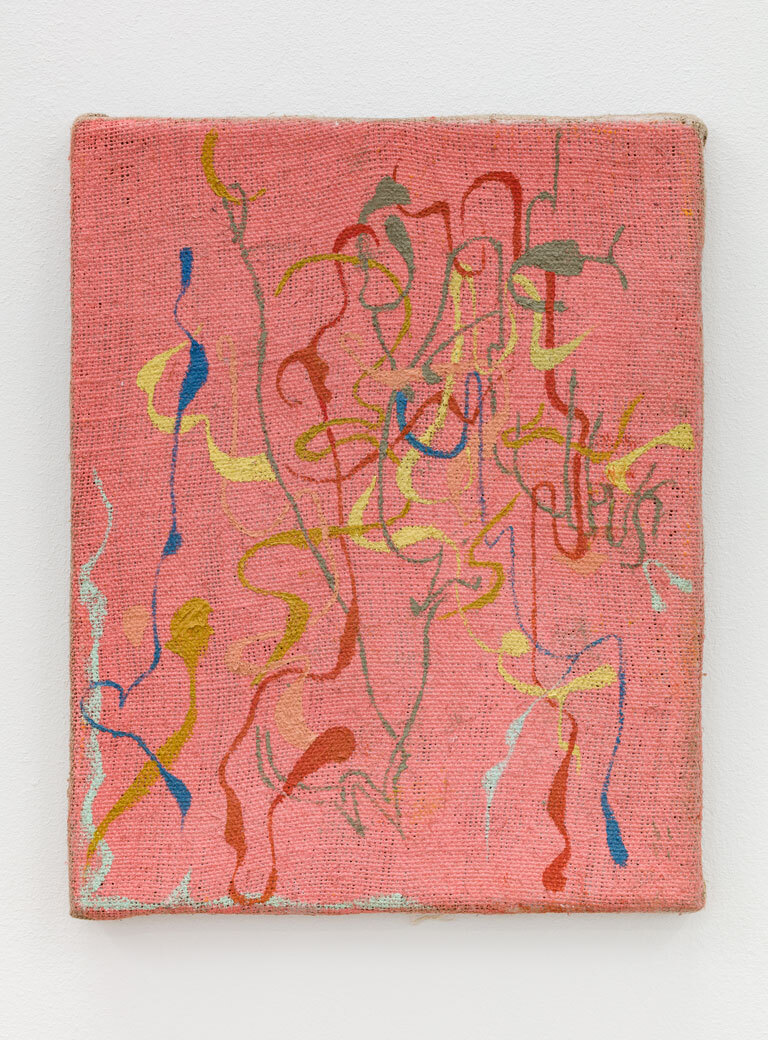

No, at some point, I standardized my image format. I work with two formats 10¼ x 8 ¼ inches (26 x 21 cm) and 18 1/8 x 14 ½ inches (46 x 37 cm). The smaller format in particular is very practical; it is found in many industrial products. I work on many paintings simultaneously; usually around 50 to 60 pieces. I start with a sketch, which I vary 30 to 40 times. Chance plays a big role in this, in that I use different colors.

Is the initial sketch representational?

No, it always starts from a gesture.

The gesture is intuitive and spontaneous, or is there a concept to it?

It is mostly intuitive and spontaneous. I develop the gesture increasingly further by repeating just two or three strokes. The more often one repeats something, the clearer it becomes. In design, it is not unusual for a logo to be worked on for a year. It becomes more and more precise the more you repeat and look at it. Drawing is comparable to writing notes and painting is like making music.

“Score” was the topic of your diploma.

Exactly. Every single painting is like a new attempt to play one and the same score. The result varies, even in classical music, depending on who is playing the piece. If the two pianists Tatyana Nikolayeva and Martha Argerich play the same score, from the same notes, the same pattern, it feels different for each of them – a different mood. Even though it’s the same piece, one really feels the person behind it. Is template a good word for it? Maybe it’s more of a blueprint of the musicians’ different moods.

Do you make music yourself?

No. But music is a good comparison, because I feel music is the most profound and emotional of the arts. Or the most general, if you will. It can also be said: Painting is poetry. Shapes rhyme with each other, colors rhyme with each other. And then you can put in content, which would be the invitation into the poem.

By content, do you mean the representation in the painting? Does the content arise spontaneously, or do you have an idea in your head when you try out the gesture in the sketch?

Tal R once said that when he paints an interior, the interior or the figure is just an invitation into the painting. Basically, everything is abstract, and our brain interprets the shapes, makes an apple out of a red circle. I try to create my paintings in a similar way according to the drawing template, like pianists play: as if I only had this one time. I could over-paint, but the painterly gesture is like a seismograph that records what state one is in, how one is feeling at the moment. It is a unique moment, it cannot be repeated. This is even truer for drawing than for painting.

You use clay, among other things, to prepare your paints. How did you come to do that?

During my time as a student, I also assisted a restorer, working on several hundred year-old paintings. Of course, at the academy I also learned how to prepare paints. The historical paints were usually a touch more muted, more subdued. In contrast, the paints produced today are perfect. Each tube of paint stands predominantly for itself, so that – as soon as you add a second color – you have two ideal entities, almost like two towers standing on their own. I often find it difficult to build a bridge between the two, because tube paints stand so strongly for themselves. The paints that I prepare myself are not as perfect and they are softer. To find even softer, more muted hues, I began working with clay. I often prime my canvases with clay, which I mix with water and later, when painting, with pigment. In the process, a lot is left to chance; you never know what will finally result. But painting in general entails a certain degree of risk. For my presentation at Belvedere 21 as part of the exhibition About the New – Young Scene in Vienna in 2019, I painted a wall with clay. I wanted to create a mood reminiscent of dew that covers everything. In the same way, this particular hue should float over everything.

What do you apply as the painting layer on top of the clay primer?

I mix clay with pigment, which absorbs the color. I like the muted quality so much. Even in a very small room, a work like this doesn’t look cluttered, it doesn’t scream at you. It’s very important to me that the paintings – each one on its own – are restrained.

Is it appropriate for your works to hang on the wall for themselves when they are created together?

They belong together, but they can also be separated. I would like to compare it to music: You can take out any song from a music album, and from each song you can take out a sequence.

A younger generation of painters has already grown up with new media. That has influenced the way they work. How is that with you?

Yes, my generation, too. At some point – that was ten years ago – I got tired of looking at each picture, especially paintings, on a small screen. It’s just a lamp shining in your face. Every texture is broken down. The beauty of painting is that it exists materially and so many textures are possible with it. The painting on the canvas functions like a three-dimensional object. Being exposed to different surface textures was part of the reason I started mixing my own paints: Plaster or clay simply behave differently than a store-bought, acrylic-based primer.

Does the choice of a small, roughly square format have anything to do with the Instagram format?

No. I chose the format because it’s easier to paint many small works of the same size than many of different sizes. The more standardized the format is, the fewer variables you have. For me, that means one less decision I have to make. When I’m working on so many paintings at once, it helps not to have to think about the format. There’s also something much more intimate about a small than a large format, and I appreciate that.

Do you have role models in art?

I immediately think of people who are not from the genre of painting, but whom I appreciate: I have always admired the dancer and choreographer Pina Bausch a lot. I also like the Japanese fashion designer Yōji Yamamoto’s attitude. Björk, I think, is crazy great! I have some friends in the contemporary art scene whose work I appreciate: Kerstin von Gabain, for example, Angelika Loderer, and Rade Petrasevic.

You co-founded an art space and a temporary exhibition project with Pina and Haus. Can you tell us more about it?

My commitment to Pina and Haus goes hand in hand with my development as an artist. The year before I was awarded my diploma, I founded Pina with Bruno Mokross. Then in succession, I received my diploma, the exhibition at Belvedere 21 was held, as was finally the show at Zeller van Almsick. Three years later, we had already had more than 30 exhibitions and several trips abroad with Pina. This is also reflected in one’s thinking and in one’s own work. One becomes more relaxed about many things. In that sense, Haus is an acceleration of what Pina gives me as a learning process. Haus took place in September 2020 in a former residential building in Simmering, in Vienna’s 11th district. All rooms of the building, from the kitchen to the garage, were used as exhibition spaces. The open call for participation was directed at artists and curators as well as institutions or any form of organizers of art projects.

Will there be a repetition?

Haus will be repeated annually. The project sees itself as a platform for testing new forms of exhibiting.

The website states that Haus aims to fill a void between the art market, institutional academic approaches, and independent cultural production. It takes a collaborative approach. How did you experience the concept of community?

We are a team in which everything is done at a grassroots level. That’s exciting for me. Similar to how it was during my studies: one can observe how the others develop and ultimately learn along with them. That is also the reason why I co-founded Pina. As an artist, one is always within one’s own four walls, but then other artists and curators come in, and one can suddenly observe and witness how they make something different out of the space each time. Because of collaborative projects like Pina or Haus, I also was spared the experience of post-graduation crisis, from which so many suffer. Because of that, for me the experience of being a student hasn’t come to an end, rather it has continued.

And you are in a permanent exhibition business…

I would like to put it this way: My works would look different if I didn’t have the art space. Through the ongoing examination of the presentation and reception of art, my own art production leads to an essence in the sense of concentration of what I want to express. We do ten exhibitions a year for Pina. Last year, due to the pandemic, many artists were unable to participate; which was a great pity as far as I was concerned because I missed the personal interaction.

How important are the visitors for you?

Of course one is happy when visitors look at what you and the other people involved have worked on. Pictures on the web are quite good, but you only really experience an exhibition when you do so directly.

I imagine that it is exciting when you present your work to the public and thus open it up for interpretation. Surely misunderstandings can also arise?

This confrontation with visitors happens all the time, and at some point one becomes calmer as a result. It’s okay if people don’t interpret my art the way I understand it.

What impact has the Corona pandemic had on your work and on art in general?

For me personally, the last year has been a good one. One change is that you become more international and more regional at the same time. Exchange with artists from abroad has been reduced, the city and the art scene miss this exchange very much; I really hope social distancing doesn’t become the norm. It appears as though we’re experiencing a kind of Biedermeier revival. Many people stay at home, one can’t travel, that saves money with which things for the home can be bought; that can also include art and perhaps would include something that feels more private than representative. I think a lot of people who have bought my work have chosen to do as something they can live with. This is fantastic, although it still feels strange.

The muted hues of your paintings evoke nature. Does nature have a special meaning for your work?

Very much so, for example in the exhibition at Zeller van Almsick. Art Nouveau forms are strongly influenced by the plant world, they are an interpretation of natural forms as modified by man, and that is more important to me than painting directly from nature. There is a book by Ernst Haeckel from 1899 called Kunstformen der Natur which contains very beautiful prints of sea creatures. In the prints it becomes clear what I mean: actually everything is abstract, everything is form and color, it is, after all, arranged by someone according to aesthetic models.

In your exhibition Amygdala at Zeller van Almsick, botanical models were juxtaposed with your works.

Kerstin von Gabain, who is a sculptor herself and curated the exhibition, had the idea that we build a bridge between the botanical models as sculptural counterparts of my work and my paintings. So I made the pedestals and used them to make sculptures for the first time. They were meant to be as simply cobbled together as are my picture frames. These models have such abstract qualities, and the pedestals were meant to act as an introduction to the paintings. The pictures shown were then a kind of combination of painting and graffiti. In Vienna, you see a lot of Art Nouveau architecture and metal lattice gates that pick up floral elements. The plant forms are actually pretty close to the natural forms. Writing, after all, originally copied the representational. The wrought iron elements often have a more beautiful sweep than the graffiti drawings.

Edin Zenun, AMYGDALA, Exhibition view, Courtesy Zeller van Almsick and the artist, Photo: www.kunst-dokumentation.com, 2020

Edin Zenun, AMYGDALA, Exhibition view, Courtesy Zeller van Almsick and the artist, Photo: www.kunst-dokumentation.com, 2020

Hard Boiled Babe, 26 x 21 cm, oil on canvas, Courtesy Zeller van Almsick and the artist, Photo: www.kunst-dokumentation.com, 2020

Thiter and Yon, 26 x 21 cm, oil on canvas, Courtesy Zeller van Almsick and the artist, Photo: www.kunst-dokumentation.com, 2020

Interview: Barbara Libert

Photos: Maximilian Pramatarov