Combining scientific research with highly detailed yet fictional narratives about the characters that inhabit them, Nivi Alroy’s works can only be described as alternative universes. They often take the form of three-dimensional installations and videos and begin most often with meticulous drawings she prepares beforehand. Through them, she depicts the unusual journeys her heroes and heroines experience as they cope with climate crises, recurring floods, disproportionally large flora and fauna and a sense of doom brought on by wild experiments that spin out of control.

Nivi, let’s begin by discussing your creative routine. How do you divide your time at the studio? What stages of your work take place here?

There are two spaces here: One is dedicated to drawing and painting, while the other is where I sculpt and do the hands-on work. I started working in this unique studio a bit before the coronavirus broke out, and I have two young children, so there have been long periods when I couldn’t really get here. When I do come here, the studio feels like a safe haven, some space beyond time. It is the place I always yearn to come back to. If you followed me every day, you would see me carrying loads of materials and installation components from the studio to my house and back. Sometimes I also work at home, during stolen moments. Currently, in addition to coming here in order to draw and sculpt, I am also shooting a film inside the studio. There are days when I come here with a whole crew of people, who are helping me simulate the rowing of a boat for an upcoming project. The studio has temporarily become part of a world that I construct. The line between reality and art has blurred a bit, but it seems right for my kind of work.

Your projects are indeed very complex and multi-faceted: They incorporate numerous mediums and introduce viewers to all-immersive narratives, kind of like divergent book plots. If you had to point out one subject that unites your entire artistic corpus, what would it be?

My work is always about the human body. I try to squeeze and extend its limits through my creation... a bit like Alice in Wonderland who becomes too big for the house she’s in and tries to find her way out. Only when I make art do I feel that I can have a true encounter with myself. I am often told that I’m a verbal person, and the worlds I create are certainly full of words. Nonetheless, for me the process of art-making is so tactile. It’s about creating something you can touch, something corporeal.

When I don’t create I feel the longing for it in my body. When I take action, I save myself. It’s a healing compulsion.

Your work often involves a lot of scientific research, but I know that your favorite medium and the one you had started with in the beginning of your career is drawing. So what does the creative process look like? Do you start by drawing images or by conducting a theoretical study?

The final result might be a visual one – a video, a drawing, an installation – but each time I arrive at it by a different route and via a different kind of research. My partner is a scientist who researches molecular marine biology. You could say that we come from two entirely different worlds, but it’s not really the case. I see how obsessed we can both be about our individual researches, and it’s quite comforting. We think about it as we prepare dinner, as we take a shower, as we put the children to sleep. The only thing that saves me from delving into research exclusively is the knowledge that as soon as I present one project or exhibition, I will immediately be jumping into my next bout of research. I’m already jumping into my next research. Over the years I have collaborated with a lot of individuals, be they artists or scientists, and that deeply enriches me. I think that through art, I try to forge a certain kinship with other people in the world.

One of your most significant collaborations took place in 2015-2016, when you were selected to be a visiting artist at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University. What did you discover there?

It was a very meaningful two years in my career. I started working then on a project called Reprogramming, which was the result of a collaboration with brain researcher Prof. Eran Meshorer. If I were asked to put it simply, I would say that Prof. Meshorer reprograms time. He reprograms 72-year-old cells into 6-day-old fetus cells, and from them he develops neural cells. Meeting him, and through him discovering the option that time doesn’t have to be linear, has changed my life. The project started when I came upon a wooden board with a drawing of a primordial forest on it at the university’s Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences. The drawing on the board reminded me of my earliest memory of a stinging nettle in the backyard of my home that caused irritation to my skin. In Reprogramming, which was an installation comprising a video, sculpture and watercolor drawings on paper, you can see a drawing that is drawn and erased so that the constructed image is perpetually changing. The drawing of stinging nettles appears on a round screen that looks like a Petri dish; gradually it turns into an image of stem cells that are differentiated into neural cells. Through a pair of holes (resembling binocular eyepieces) what is then seen seems like a lawn – my primal memory. Overall, my time at the university was like what children probably feel when they enter a candy store … absolute pleasure. I met with researchers who told me stories and taught me. I collaborated with six of them simultaneously, and it was overwhelming but also provided a lot of motivation and interest.

I assume that there were many ideas that were born during that residency, which you haven’t turned into artworks yet. Is there a dream project that you would like to tackle next or a new mode of creation you would like to pursue?

As an artist, what always bothered me is that I create a world, but after I display it, there comes a point where it s is no longer evolving. I have this aspiration to create a world that will exist independently from me and live on after me, producing its own climate, plant growth and distribution, and self-regulation. Artists like Pierre Huyghe and William Kentridge stir up so many emotions in me because they succeed in doing exactly that; they create meta-worlds. The readers of our interview can’t see where we’re sitting right now. The Scottish House where my studio is located, also known as the English Hospital, is a building with a unique history which is marked by a character who lived here and treated the ill. I believe that her ghost still walks the hallways, some 100 years after she died. In my trilogy Mariana Trench, I focused on the character of U.S. geologist and oceanographic cartographer Marie Tharp. Having created the first scientific map of the Atlantic Ocean floor, she quite literally embarked on an expedition to map out what she couldn’t see. I can really sense some similarities between her and Beatrice Mangan, the Irish missionary-turned-nurse who founded this place. I would love to create a project about her and the Scottish House, which will soon disappear and be turned into a boutique hotel. Tracing the footsteps of people from the past is a habit I’ve had for decades: I create projects, but then I also make up characters who drive these projects, and appear to support them. This comforts me greatly, because I know that even after I leave my studio at the end of a day’s work, they will still be there. In that sense, my work is about memory as well as about a confrontation with time and its passage.

Well before the pandemic entered our lives, your art dealt with a certain anxiety over a looming apocalypse, seemingly expressing a morbid longing for the world’s end. Has the outbreak of COVID-19 changed anything in your approach, method and style?

A day before the first lockdown in Israel began, I was sitting down with Drorit Gur Arie, the curator of a project I am working on that deals with the idea of what the first day post-flood will look like. It’s the third sequence of the Mariana Trench trilogy, and it is in the form of a pop-up artist book. The curator was telling me: ‘Oh, your project is so timely.’ But all I could think was that my life had turned upside down. I am constantly toiling to create a world that exists entirely inside my head, and suddenly I felt that I had travelled to the other end of time. All of a sudden, this virus spread and it made me wonder whether the post-apocalypse was even something I could imagine anymore. I abandoned all the work I had done for the book and started over, this time under the impression that perhaps the doomsday that I keep dreaming about in my art is approaching in reality. The book will not contain illustrations of viruses, but it will relate to this collective disaster through my attempt to understand emotionally the experience that we have all gone through – this feeling that something became unravelled and has now has to be built anew. When I started working on my book and the video work accompanying it, I imagined this idea that was prevalent in the Middle Ages – that the world is flat. In my mind’s eye, I saw a ship sailing on that flat world and falling off the edge. That’s where life will start over. Now it feels like this is really happening.

Mariana Trench (detail), a site-specific installation, part of a solo exhibition, The Herzliya Museum Of Art, 2019, Curator: Dr. Aya Lurie

The Mariana Trench-Flood, an animated video and radio play written in collaboration with Moran Shoub, 2019

The book is the third chapter of a trilogy that began with a solo exhibition you had at the Herzliya Museum of Art in 2019, where you presented site-specific installations that portrayed images of the world post-extinction. The figure that drove the show was a tribute to scientist Marie Tharp. What process have you launched since then? What will the book include?

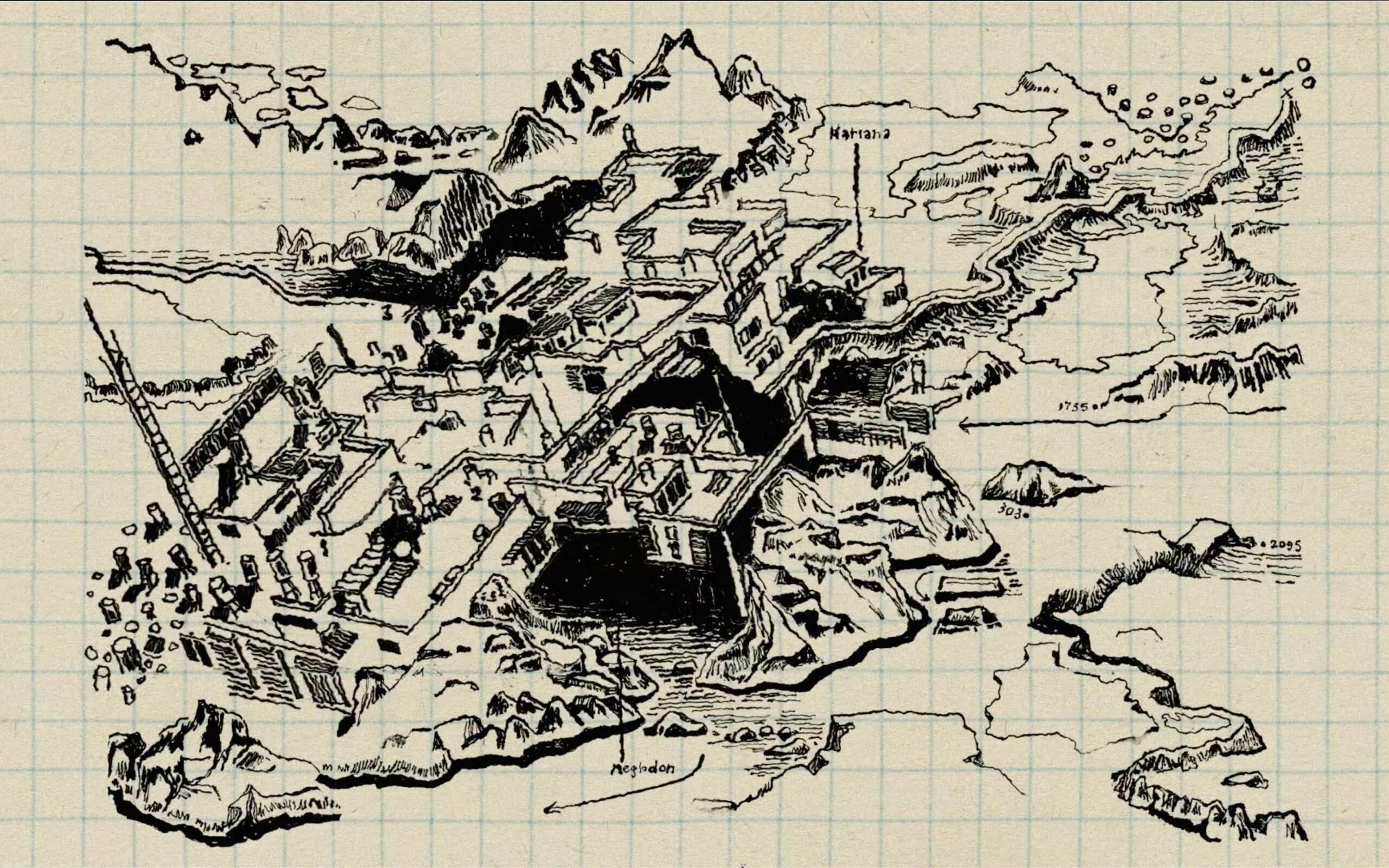

The book – which is slated to be published this upcoming winter – contains maps and a codex, like a kind of visual dictionary guiding readers through the post-flood world. In the exhibition, I showed a moment when humanity lost control because of one woman who lost control, whereas the book focuses on the moment when things start growing again after all cultures have been destroyed. The book also contains drawings of characters I invented, who are kind of trapped within it and floating. It is really interesting to create a world made entirely of drawings, because it is the medium where I feel most coherent and at home. Simultaneously, I’m also working on a project called Odyssey H2O: An Expedition to the End of Time. It is a video installation I am collaborating on with Israeli artist Atar Geva; together, we are trying to float boats beyond time. So what I’ve been doing this year is basically pushing boats around (laughs).

Do you believe that the ongoing preoccupation in your art with the idea of an end stems from a hope for deliverance? Are you creating bleak visions in order to fight the existential despair?

I think about this a lot, both as an artist and as an art teacher and lecturer. I believe that a lot of my work pertains to the notion of a lack of control. We are in the midst of a situation in which we have lost all control. There is something very liberating about losing control, kind of like living a self-fulfilling prophecy. All of my artworks are sort of an effort to map out a flood, to map out chaos. With art, I am able to create a compass for myself, which helps me navigate through this primeval and physical fear that I have. I make art in order to cope with strengths and weaknesses, with life itself.

Interview: Joy Bernard

Photos: Adi Shraga