Ovidiu Anton is a sculptor who concerns himself with borders everywhere in the world, and what they mean to the people living near them, or trying to cross them. He thinks about the movement in the public space and its delimitations, possibly hailing from his experience growing up in Rumania in the 1980s. He then uses his formal language to work out his ideas, using his favourite material: wood.

How did you become an artist?

Well, I liked drawing of course, but I went to a high school for timber construction and got interested in architecture. But when I wasn’t accepted at the architecture department at the University for Applied Arts, I went to a school for artistic photography with Friedl Kubelka instead, and I loved it. During my high school years, I had been part of an environmental protection group - I liked the activist aspect of it. But as an activist you are just like a soldier, it’s not creative at all, so doing art was much more satisfying.

And you never looked back?

Right. I integrated the Academy of Fine Arts, in the sculpture department. I am interested in space, the body and how the body acts in space.

What is your working process like?

I start with turning ideas around in my head. This happens mainly when I travel: for instance, each summer I undertake a long bike tour, last year I went to Bretagne. Biking up to 200 km a day is like meditation. It took me eleven days to reach the Atlantic coast. Thanks to this slow pace, I can see and smell the landscape. There is time to reflect, wind down and develop ideas. In the autumn, I put my thoughts together, and end up with my themes.

Which are?

The public space, and hierarchies within it, what is forbidden there and what is not, and how we deal with it. I’m into thinking about what we are allowed to do: I spend a lot of time near borders, which is an important issue for me – also for biographical reasons.

Talking about borders: Your piece Patchwork was centered around the US-Mexican one. Can you tell me about that?

I spend six months as a Schindler scholar in LA in 2019. It was the end of the first Trump presidency, and border patrol was severe. People trying to come into the US illegally were cutting holes into the border wall, which is a fence actually. These are the kind of movements I am fascinated by. And so I watched the border between Calexico und Mexicali; when the welders arrive every morning to mend the fence. And sometimes the patches they fix it with might get cut off again the night after, like in a game of cat and mouse. From far away, the fence looks fine, but from near, it is full of patches.

So in your own way, you documented what was happening there?

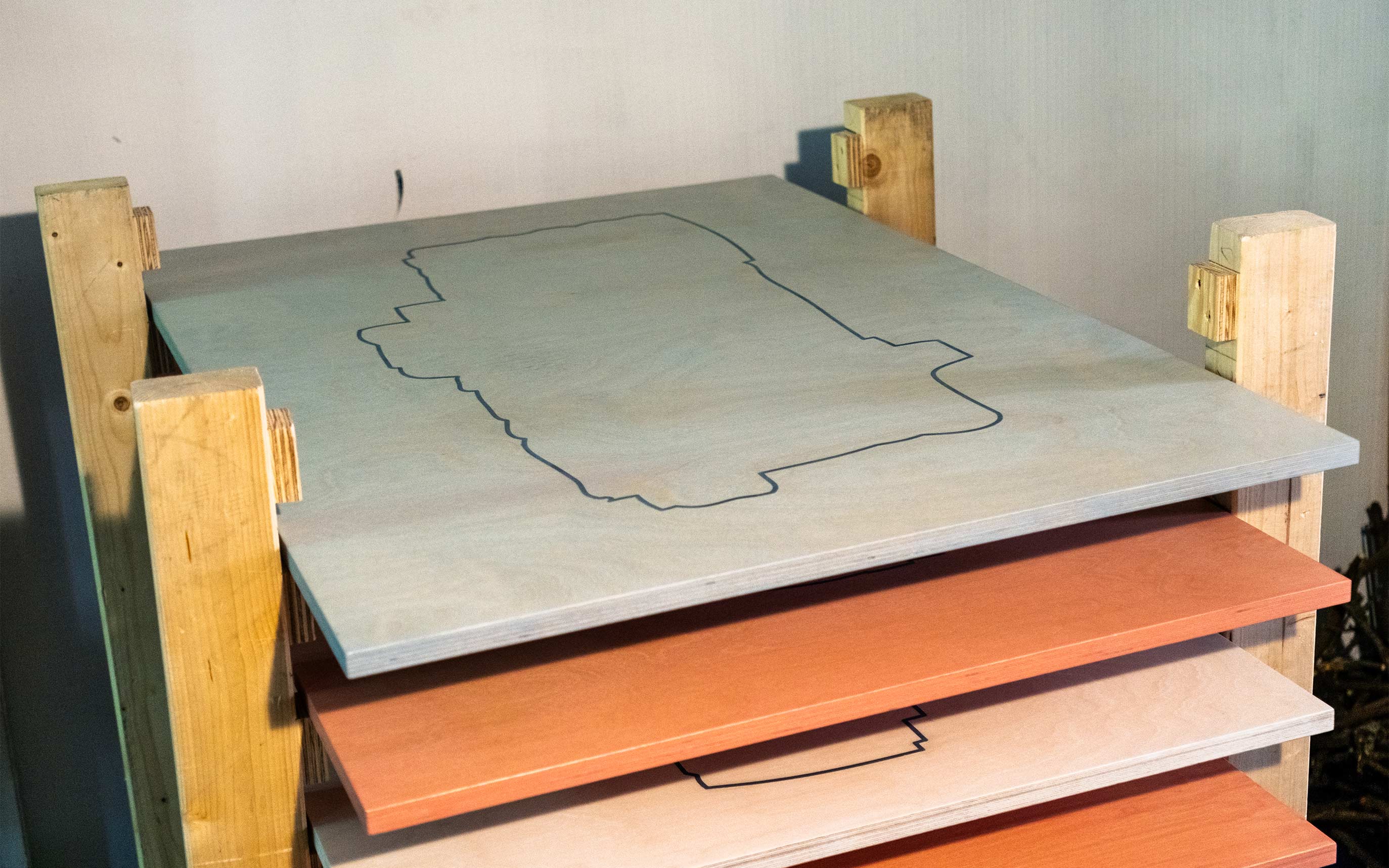

Yes. I researched the fence’s functions, construction and state of repair. And I looked at these cut-out patches and used their shape to make life size sculptures out of wood.

Did you measure them up before?

Yes. I took my measuring tape right to the fence!

Did nobody intervene?

Oh yes, I had lots of problems with the border patrol! On the Mexican side, nobody cares though, so I walked over from Calexiko to Mexicali, measured the patches and sketched them. But the US border patrol had seen me on camera from the other side, and when I walked back into the US there were lots of questions! Sometimes I had to stay for hours on end, but eventually, they always let me go… It wasn’t easy, but the border theme always gets me going!

Which brings us to your biography! You were born in Timisoara, the city where the Rumania revolution started in 1989, but by then still under Ceausescu’s rule…

My dad was a dissident. After the revolution, when the borders opened, he left for Hungary, then ended up in Austria. One year later he sent for me, my sister, my mum; I was nine years old at the time. And I went to school and studied here.

A successful integration story!

Yes, but it was so much easier for us kids than for my parents. When the time for my thesis at University came, I wanted to recapture my dad’s trip to Austria through my art. This was the first work I did about borders. I interviewed him about crossing over the green border, hiding for hours on end. I presented it as a multi-channel installation retracing his steps.

When you talk about it, this work also seems to have a documentary side to it. Where does the art come in?

I want to do more than just documentation. Because that is something for journalists or scientists to do, checking sources and so on. The advantage that I bring to the table is that I am concerned with formal issues. So for instance when I look at the US – Mexican border wall, I see patches and their individual shapes.

So you are concerned with the individual aspect?

Well, you could almost say I’m autistic. I have a tunnel view and focus on certain things, and then just go for it. It just clicks.

Is it easy to have that click?

Not if you want it at all cost. But if you give yourself enough time…

Like on your bike tour…

Yes. I have something like a cloud in my head with everything that interests me.

Do you take notes?

All the time, by hand. And I sketch. And then I become confident that this is what I want to invest myself in, and I just go for it. Right now for instance, I am dealing with different shapes, with nature in the public space. How constricted we are, how we constrict ourselves. I have started working with more organic forms, loops, geometrics that nature provides us with.

To bring some movement into the public space?

There has to be so much order in the public space, and I want to create a kind of material anarchy. But if I was just talking about it, my job would be that of a theoretician or a writer. However, I have a formal language, and I put my thoughts into a form, a language, a medium, a shape. It is how my world works. I make connections between things that I express in an artistic, and not a scientific kind of way.

You mentioned the public space: In another work of yours, you dealt with graffiti…

I took pictures of these slogans, drew around them, blew them up – this is how I caught the movement. It’s funny: A sprayer has to be very quick to write on a wall, but then I spend hours on a drawing, reproducing it. It feels like I inverse time! This is what gives those slogans a certain monumentality. To me, they are a communication tool in the public space: little monuments that are on the street for a short amount of time.

Talking about little monuments on the street: you recently showed tear gas shells that you had found on streets in Israel?

I went there in 2023, before October 7th. I lived not far from Tel Aviv for a few months and travelled to Jerusalem, to the West Bank, and again became interested in walls and borders. I got around a lot, to Hebron and the South Hebron hills, to Ramallah, to Betlehem… I also met with Breaking the Silence organization, where former Israeli soldiers give testimony.

What does the work look like that you made afterwards?

These cartridges of tear gas and sponge bullets that you find on the streets – they are the symbol of the spiral of violence for me personally – I blew them up and reproduced them in wood, which is my favourite material. But first, I had to clean them carefully, so that I could take them back on the plane with me! The blown-up version is now exhibited in Graz until September. Another sculpture of mine is on show too, it’s a work about the border between Serbia and Hungary. It is an observation post, which I took a picture of and reproduced.

There are lots of borders in your work: US-Mexico, Israel, Serbia-Hungary…

Yes, and I also went to Cyprus! I am just drawn to these borders.

Maybe because they remind you of the time in Rumania before the revolution, not being able to get out? What do you remember about it?

I remember the revolution, I saw it on TV. But of course, you don’t understand much as a child.

Do you remember a certain mood? Especially since you said that your dad was a dissident?

I think I felt some things. And I understood that my grandparents were listening to Radio Free Europe. I still see them sitting there, glued to the radio. And when I came in, they shoved me out. And my mum warned me not to tell anyone. But I did not think much about it.

It was your normal.

Well, what annoyed me the most at the time was having to wear a uniform at school! And at each time Ceausescu came to Timisoara, there had to be a welcoming committee with small kids, specially cast to present flowers or do a special performance “For the leader”. However, my parents were not into that! I remember that I was chosen once to participate in such an event, but my parents did not let me go at the last minute, they called me in sick. As a child, I always had the feeling that I should not know what the grownups were talking about. Until one day I understood: they were afraid of denunciation.

Do you think that feeling has an influence on your work?

Probably. I think a lot about freedom, although our life in democracy now of course is not comparable to the one we led in Rumania. But it draws me to the borders in the world.

We are meeting in your Vienna studio, but most of your work is stored somewhere else?

Yes, a lot of it is in Burgenland, where I have a storage. Here, I just produce: I don’t need to be surrounded by my art. I keep mulling over ideas for an incubation time, and production then follows. I don’t have something like a “studio practice”, coming in here every day for a couple of hours to get into a flow. It’s not my thing. Also, I need to work on the side, so I don’t have that much time.

You mean a second job?

Yes. I do exhibition building and production, I do the technical stuff, the organization… And I assist artists.

Do you see this job as hindering your practice or on the contrary as enriching it?

Enriching actually. Because there is a close cooperation with other artists, where we are discussing formal decisions, and I can give some input. I worked for the Secession in Vienna for about 20 years, and got in touch with some great artists, like Ed Ruscha or Francis Alys, Klara Lidén. She is close to my work, as it’s about streets and common spaces: it was great working with her.

When you work with an artist, don’t you get the feeling that you are being influenced by them? Can you draw a line?

Yes, sure. I am often asked about what exhibitions I see, and nothing comes to mind –I guess this is where I draw the line, because I see so much more than an average visitor that I am practically submerged by it. But I do have my limits, and I need time to process. On the other hand, many works have influenced me and gotten my own work further.

You see it as positive then?

Mostly. But it is badly remunerated, and you need to work so much to be able to pay the bills! Also, it is an unhappy role. When you’re an artist yourself working for another one, you may find that one day you work for him, but the next you are showing in the same group exhibition. That is not easy. But you learn how to deal with it, to distance yourself. Because it is what it is. The art scene is like a hegemonial game, a hot balloon, pretty inflated. Sometimes, I don’t get enough time to spend on my own work. So you get this sense of guilt…

That must be quite some tension…

When I was younger, I needed the money. Then I started doing well with my own art and could have stopped, but I still continued. Because I know how to do the job, and I like it, and I learn a lot.

What are your new projects?

There is the show called Freedom Was an Episode (tbc) until September, at the Neue Galerie / Bruseum in Graz. Another show, till September as well, at Kunstmuseum Lichtenstein, Auf der Strasse is on right now, and I am working on a solo exhibition for June at Christine König Galerie in Vienna. And there is a solicited Kunst am Bau competition in Leipzig that I am developing a project for, which I cannot talk about yet!

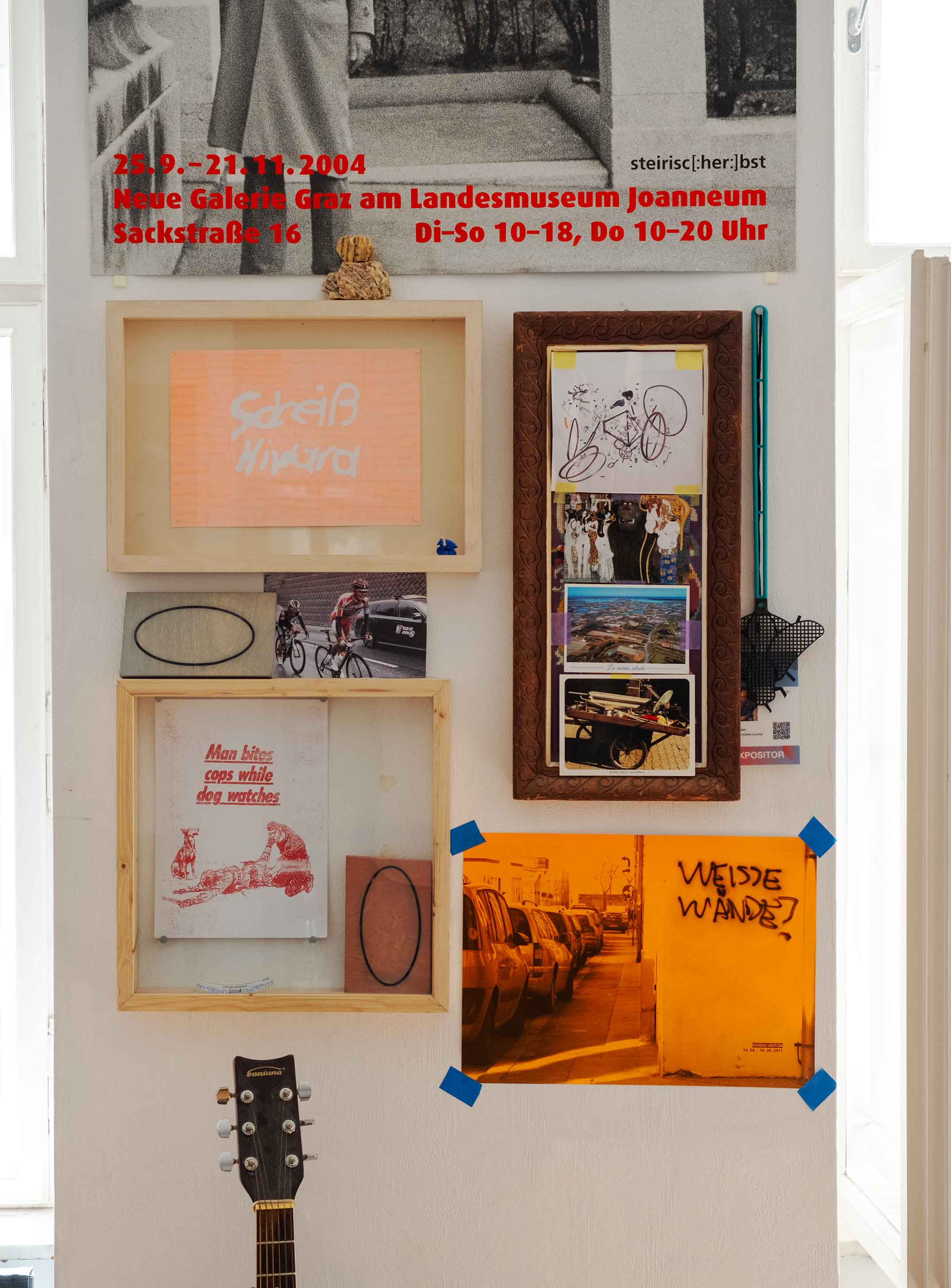

No title, 2023

Exhibition view at Freedom Was an Episode (tbc), Neue Galerie Graz and Bruseum, 2025

Photo: Universalmuseum Joanneum/J.J. Kucek © Bildrecht Wien

CCTV Post / External Border of the EU HU-SRB, 2021

Exhibition view at Patchworks, Chamber of Labour Vienna, 2021 Photo: Klaus Pichler © Bildrecht Wien

Exhibition view at Case Study / Border Monument, Christine König Gallery Vienna, 2021

Photo: Simon Veres © Bildrecht Wien

»Zeit totschlagen und Umgebung beobachten«, multi-channel installation, 2008-2010 Installation view at Mit uns ist kein (National) Staat zu machen; Kunstraum Niederösterreich, Vienna, 2010

Photo: Ovidiu Anton © Bildrecht Wien

Interview: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Maximilian Pramatarov

Links: