Sofia Goscinski is an Austrian sculptor and painter with Polish-Russian roots. Her working method is process-oriented; the work, which revolves around the question of identity, emerges during the creative process. For Goscinski, art is a means of communication with the outside world; the common thread running through her work is the joy of discovery, which is expressed in her use of ever-new materials.

Sofia, how did you get into art?

Actually, it was in my blood: my Polish father was a natural talent at drawing, and my mother had been an art critic in Moscow. Art was omnipresent; nevertheless, I tried to take an interest in other things! Since I grew up multilingual thanks to my parents, I thought about getting a degree in interpreting.

And?

Well, it quickly became clear that it wasn't for me (laughs). I then took the entrance exam at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna and studied photography there. I had been gifted a single-lens reflex camera while still at school and dreamed of becoming a fashion photographer.

It reminds one of a major Austrian figure in this field – was Elfie Semotan a role model for you?

I even worked for her later on! But I was extremely shy and didn't have the courage to approach people to photograph them. And then I discovered the work of Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin, Elke Krystufek... I saw her exhibition at the Secession while I was still at school, and it made a lasting impression on me.

So you moved in the direction of self-expressive photography?

Yes! It was also about staging, dressing up, I organised photo sessions with myself. And so I realised that I was more interested in art photography than fashion photography. The freedom and intimacy in artistic work triggered me.

Your graduation from the Academy was in Eva Schlegel’s class; in her work, too, the boundaries between sculpture and photography seem to blur…

Exactly, my approach was conceptual.

But isn't that still quite abstract as a young person?

I think it was just the time... My hero was Bruce Nauman, the ultimate! And then John Baldessari, the minimalists, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, etc. That came through my studies: we were always motivated to base our work on an idea or a concept.

What appealed to you so much about the concept?

Good question... Maybe, to put it bluntly, a certain laziness (laughs). You sit around thinking and waiting for the brilliant idea. And it has to be so brilliant that you get off your ass and make sure the work gets produced, which costs money that you first have to raise.

Didn't the early focus on the conceptual hinder you?

I have to say, from today's perspective—my diploma has been 20 years ago now—it took me a very long time to free myself from that. Now I work freely. My career moved away from the conceptual to a process-oriented approach. A turning point—when I realised that this was now taking hold—was around 2017. It took a long time to stand up and say, “There's nothing big behind it now, it's just about the process.”

Do you even dare to do such a thing?

I dare to do it now. But ultimately, saying nothing about your work doesn't make much sense. Because I've noticed that when you talk about technique or tell a story about a work in general, it gives viewers a way to connect with it.

Do you think that's important?

Of course, everyone can see what they want to see, which is very important to me. I would never tell someone exactly what they should see in a work. But I can perhaps reveal a motivation or provide an emotional entry point.

How would you describe your working method?

I no longer hatch ideas before I start working, but am constantly in the process. In any case, from today's perspective, I can say that identity or the question of identity has always been my main theme.

Did your parents' immigrant background influence you?

As a child and teenager, I always had the impression of being a little displaced, of not really belonging. Of being a little foreign, and that others sensed that too.

Has that feeling remained?

A little bit, yes. But Vienna was different back then, less international. I simply had this awareness that I had no roots where I was born and lived, but also not where my parents came from. You are a rootless person. I think that's special.

Which of your works reflect this?

For example, these small concrete works with concrete shards, I call them barricades, were created out of a personal crisis. In the process, in contemplation, I understood that this was exactly my state of mind. Being hurt, traumatised, but at the same time defensively building barricades around myself.

So this type of work is very different from what you did before?

Absolutely; especially when I think back to my first solo exhibition in 2005.

What did you show back then?

Conceptual art (laughs)! It was about the X as a form, as a letter, as a number. There was a giant X made of large black beams, a nautical flag alphabet, a text by Sol LeWitt in which I had crossed out everything except the X...

How do you view this work today?

The interesting thing was: the exhibition was successful, I sold some pieces, which was great! But then I heard two comments that made me think. One was, “this is a very intelligent exhibition” – and I didn't know whether that was good or bad. And the second was, “It's good, but maybe you should do something that relates to yourself!”

How did you deal with the criticism?

It was painful, but it really helped me move forward – precisely because I had already felt it during my diploma. But I had played it safe at the exhibition. Ultimately, however, the seed of doubt had been sown, and soon after, I began to take an interest in sculpture, in three-dimensional art.

When did you start working with your hands?

I only started working with my hands in a truly sculptural way in 2013.

Had you learned how to work with materials? How did you approach it?

Amateurishly (laughs)! I just did it. Then in 2017, I started working with concrete: it was a disaster! It was madness! I bought a bag of cement and a bag of sand and made an incredible mess in my studio (laughs). The first slabs I poured—my God! They were crooked and thick, and at first there wasn't even any reinforcement in them (reinforcing the concrete with steel or fabric). One of them was purchased by the Belvedere though...

A sign of recognition?

It's a beautiful work! The concrete was the image carrier on which I worked with paint. But from a restoration point of view, it was certainly a challenge! Now I know how to work with the material well. I find it exciting that you not only follow your path mentally and emotionally, but also learn things about yourself and the nature of the world when working with the material.

How did you come up with concrete?

Because concrete has an aesthetics that has always fascinated me. I like working with it—I now mould, pour, and trowel it. I like the colour, the texture, the possibilities. It's an incredibly beautiful medium. And then there's my childhood memory of drawing on the asphalt. And the romantic story of my father, who travelled around Europe like a hippie and earned money by drawing on the street. I love that chalk on grey.

Speaking of concrete: in an exhibition in a gallery in Innsbruck, you filled the room with concrete rubble. It reminded me of Walter de Maria's New York Earth Room. Is that also a reference?

Walter de Maria was a great inspiration. His installation at the Venice Biennale in the Arsenale was like going to church. That element also interested me in the minimalists. I always had an emotional connection to these works, found them moving. They are “untouched”: you don't see the person, only the thinking, the abstraction of form. The anonymity, only the perfect form, the perfect construction.

Can you describe what your work is about in one sentence?

Phew (ponders). I would say it's about discovery. I was, and still am, constantly searching for something new, something I can learn from... like how to work with new materials.

And taking people along on the discovery?

Sure. Art is my way of communicating with the outside world. That's why the opportunity to exhibit and show things is so important.

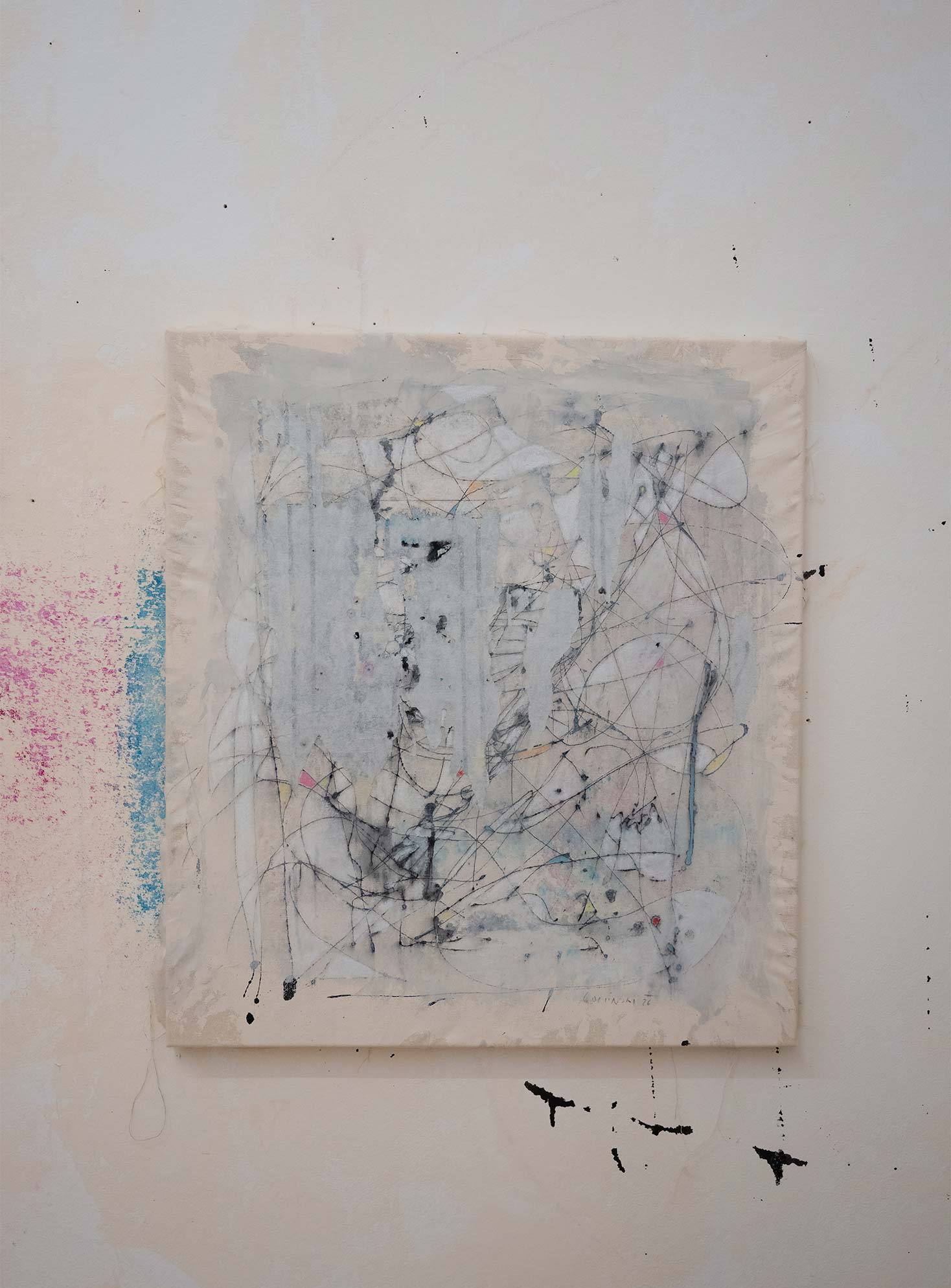

You've also been showing paintings recently...

Painting was never really my medium. Even though I grew up with it! But I come from photography, and sculpture. During my period of crisis, however, I was looking for a way to get back into the work process. So I took out a bag of old oil paints that Bjarne Meelgard had once given me and just started painting—and it felt good and was liberating.

Is it a different process than sculpture?

Very different, because sculpture requires preparation, a form – the creative part is usually the shortest part of the work! What attracted me to painting was the direct, barrier-free way of working - you don't need much. I wouldn't have dared to exhibit mainly paintings in the past, but now it has become equally important to me. Painting and sculpture are intertwined. For me, painting is never flat. Even a canvas is a body.

We've already mentioned several times the inspiration provided by other artists, such as Walter de Maria, Bruce Nauman, Sol LeWitt, Donald Judd... How difficult is it to stand on the shoulders of giants? How do you set yourself apart, develop yourself?

Well, giants... I no longer see them as giants, because even during my studies it dawned on me that they were mainly male artists. Women were still severely underrepresented at that time. I knew Sol Lewitt, but not Eva Hesse.

Have you shifted your focus to female artists today?

I would say yes, but not because they are women, but because I think the art is great. I saw Eva Hesse at just the right time: I was fascinated by her process-oriented, minimalist work. Isa Genzken encouraged me with her versatility. As influential as minimalism and conceptual art were for me, I managed to break out of it and work relatively unencumbered and freely.

How so?

I have always been a bit hesitant when it comes to my career. I'm relatively slow in my process and need the freedom to work without pressure and without external expectations. It's so important to have as much time as possible to develop your work and not to repeat yourself because of demand.

How do you feel about working and living in Vienna?

Chill (laughs). I think it's easier to work in the city where you were born because you have better access. There is good funding and an exciting scene; there is no lack of inspiration. However, the big money is not based here.

Are there not enough collectors?

In general, there is a lack of financial power to elevate local artists to the international stage.

What are your current projects?

I'm currently working on an exhibition with Daniel Domig, which will open in February at Galerie 3. I'll be showing small sculptural works and paintings. Then in March there's a solo exhibition at Alexander Giese's Klubhaus, an invitation to fill a display case on Karlsplatz; and other projects that aren't ready to be announced yet.

Text: Alexandra Markl

Photo: Christoph Liebentritt