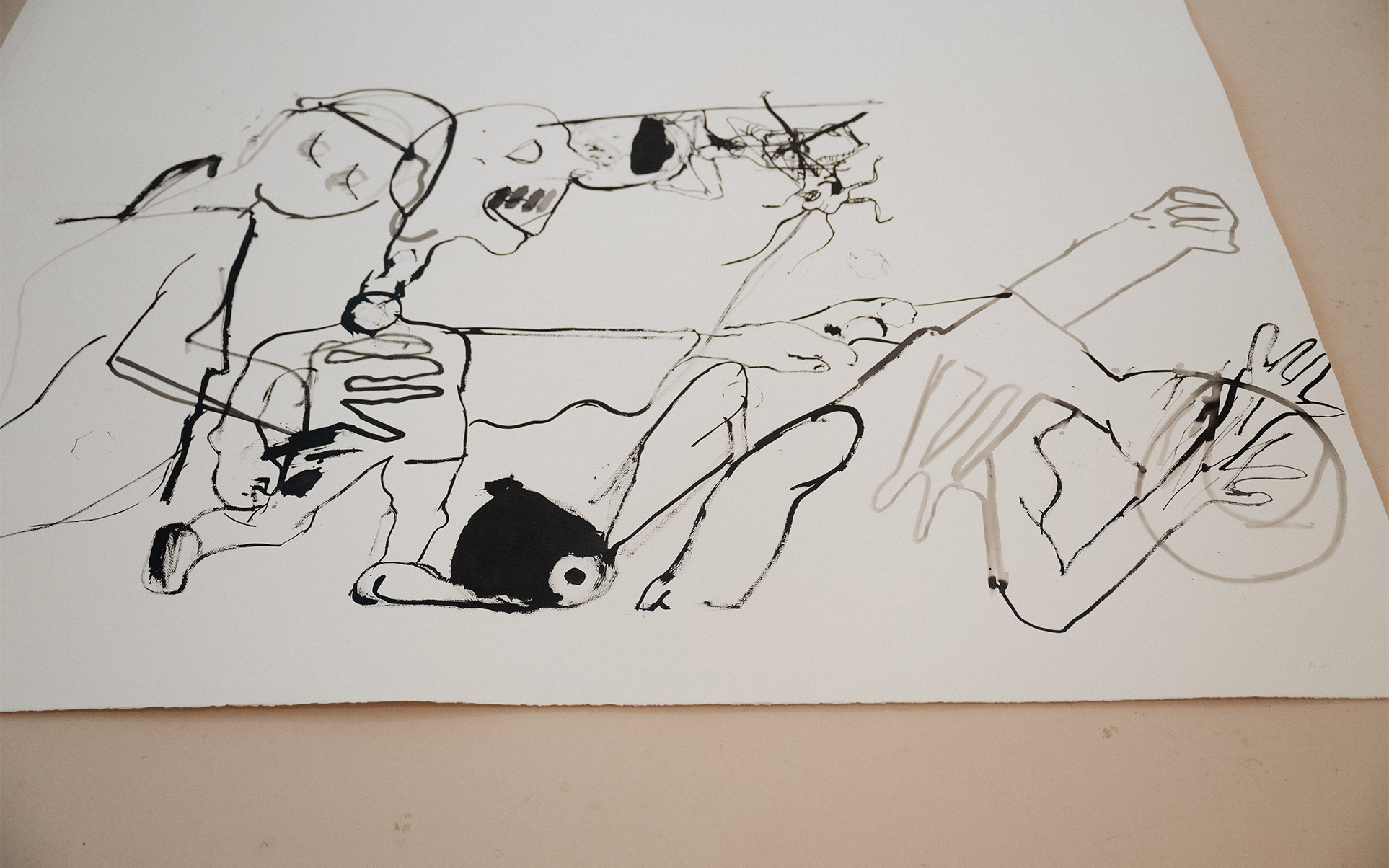

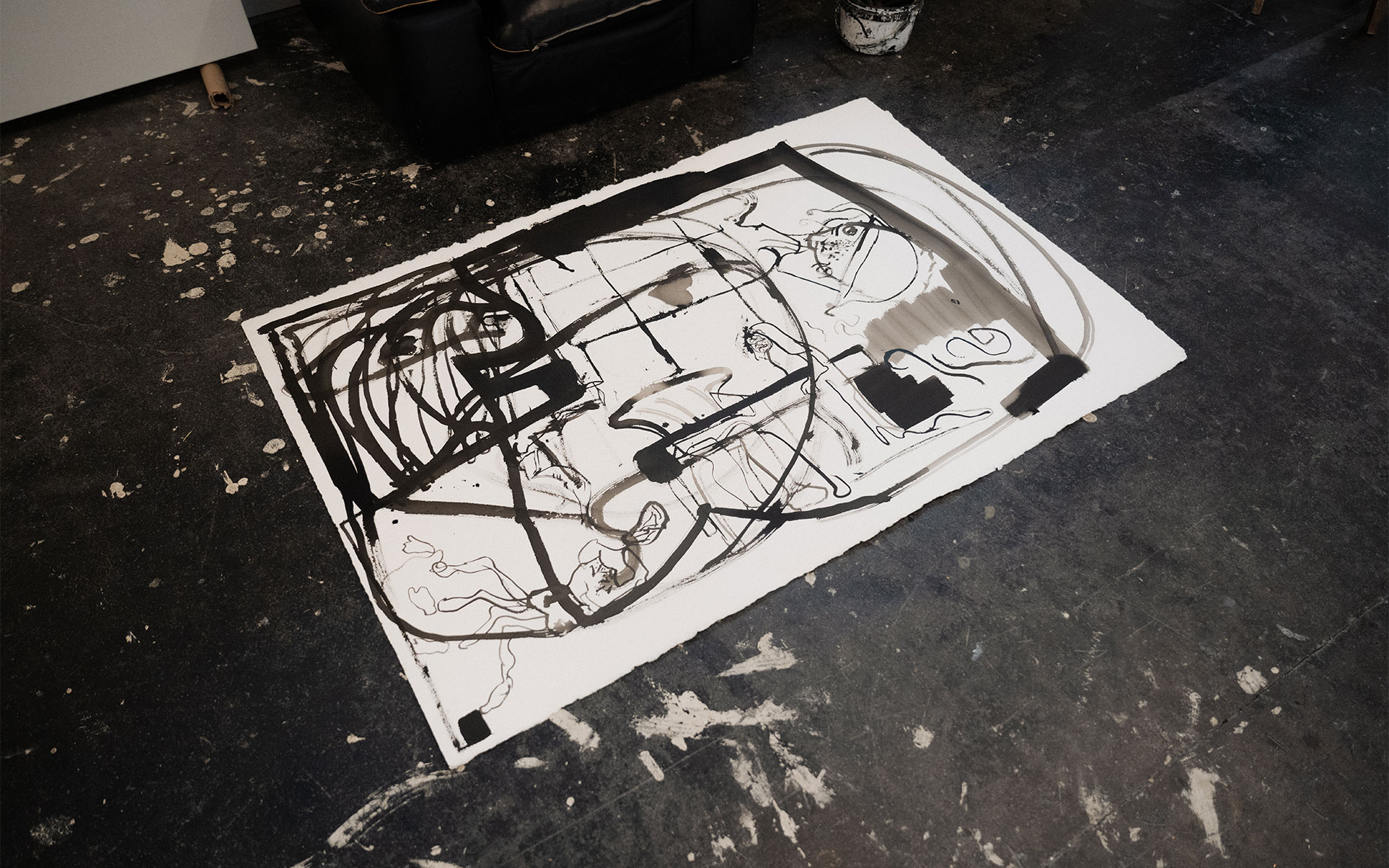

The Austrian painter Tobias Pils approaches the canvas with a precise idea, which he then executes in a muted color palette. He lets the energy of his subject speak through him, but is careful to add a certain estrangement to the work, so that the result offers a possibility of connection for everybody. Pils mixes abstract and figurative elements and thus constructs a multi layered composition. Once he is finished, a window that opens up in the work that will lead him to the next one, therefore placing his paintings into a process of creation.

How did you get into art?

My father studied at the Academy of Fine Arts under Josef Mikl and often would take my brother and I with him. I can remember walking up and down these stairs. And thinking: I want to do that one day. However, a colleague of my father’s told me then: “Don’t. It’s horrible being an artist”. My reaction: even so. When I was 17, I started drawing daily. And in my naïve delusions of grandeur, I applied successfully for painting and graphics.

How do you start your working process?

It is an ongoing process. One painting begets the next, because each contains a moment that continues to interest me. It is like a window that opens, and through it, I slip into the next work. Before I start painting, I have a very clear idea or a feeling that I want to materialize; sometimes it can also be a special temperature or a motive. If I don’t have that, I won’t start. And then, I just let the energy of the theme run through me. And there also needs to be a certain estrangement to the work, so that it can be a projection surface for everybody.

From the personal to the general…

Yes, and the other way round, too. Friederike Mayröcker wrote: “from the outside to the inside and from the inside to the outside”. And she meant that the easier part is to get from outside to the inside, but going from the inside to the outside, that is the crucial element of form finding.

And the artists’ job! How do you find your motives?

They crystallize during the working process. It’s always the same motives - they shift, mutate, disappear, and then reassemble.

What are your standard motives?

I think it’s a mix of figures, glimpses of nature, sun, trees, twigs, weather, eggs in different states. And each of them means something else at the same time…

And with these motives in your mind, you stand in front of the white canvas?

Not always just with the motive, but also with a certain idea of conception.

Are you somebody who already sees the piece and then paints it “from memory”, or do you work in the moment?

Sometimes I might see it in front of me, but one is limited. But through this limitation in one’s own ability something new emerges. It’s in the doing and making - not just thinking but doing - where the possibility of a transformation lies, I think. And this is what art is all about. “Just” the right idea might come quickly… Van Gogh’s sunflowers, for instance: the work is about sunflowers too, but really about metamorphosis.

How to give them new meaning?

Yes, and this takes time. You need to think it, but also to feel and do it.

You said that one is limited in one’s own ability. Do you get the feeling that you are growing with every new work, that you are somehow “getting better”?

It's not about “getting better” at all. I am interested in movement. One moves around, sometimes in circles. But it’s about wanting to dig deeper. An artist’s task is not to become more professional. But for his work to get deeper and more transparent, to develop another form of language.

Have you developed your own language?

I don’t want to judge! Generally, I don’t believe in solutions. I have this feeling of unrest in me, or this desire to move, to move further. I don’t want to be caught in my own bubble, but probably there is by now a sort of grammar that I have worked out for myself.

This becomes apparent to viewers who recognize your work when they see it. Do you think that your grammar is unique to you?

Well, I think this is the basic requirement. However, this kind of self-reference often annoys me, too.

We live in a time where self-reflection plays a major role. In literature, there is autofiction, and in art, much revolves around identity, too.

One the one hand, I take that for granted. On the other hand, I like that art is a genre with a previous history; and you become part of this special story and find a moment that is new and different.

Is this the task that you set yourself?

Yes, maybe, but it just happens over a longer period of time. There are also moments that amuse me, that further me on. For instance, motives in my works that hark back to other works in which they have already been used, and which I have transformed and translated. And if you do that with every picture, a whole painter’s practice emerges.

You have been talking about removing the narrative from the picture. Is it important to you that the paintings don’t tell a story and the viewer finds his own interpretation?

I think that three months ago, I might have said that I didn’t want any narrative, no story to be told. Meanwhile, I don’t trust that statement anymore. You cannot read a story in my paintings. I would rather eschew it, and if it becomes too illustrative, I try and remove exactly that. So that the viewer can have his own interpretation, and no classical story can be read.

Do you find any interpretation valid, or do you think they can be a bit of a drivel sometimes?

I might think that sometimes (laughs). But I like to set the paintings free and see them in an exhibition. Everybody can think of whatever they want.

You open up a lot without giving directions.

Well, while I paint, I don’t think about content, but just about form. I believe that form comes before content.

Content follows form?

Yes. If that works for me, the rest follows automatically. It’s like a framework with specific viewpoints and formal and conceptual cues, but ultimately, the viewer puts it together on their own. It’s not that easy actually: you need to find the right form to be able to really express yourself. And then you must combine it with motives or content to open up another window, to create a different kind of energy.

Some time ago, you said in an interview: “Skill is limiting, but so is non-skill.” Do you still stand by it?

In the right context, yes. I think that one has to allow ambivalence. And that discrepancy in a painting might not be discrepancy at all.

Maybe it’s more interesting if there is not one way to see it…

And yet, the painting needs to be absolutely clear! Work needs to be of its time, but out of it too. I find that Alberto Giacometti is a great example. His sculptures could have been conceived thousands of years ago, but at the same time, they are clearly anchored in the 1940s and 1950s, but they could as well come from the future!

Since you mention Giacometti: Some people say that your figures also have something from the modernist era. Do you agree?

Yes and no. When one paints, one is always part of something much bigger. I find that without one foot rooted in the past, you cannot confidently act in new territory.

Meaning you should know who came before you?

Every brushstroke that you do has been done thousands of times before. Pictures do talk about other pictures. This is the beauty and excitement of painting: that you have such a small radius, but if you enlarge it, something new emerges.

A continuation in the frame of the history of art…

Yes, you reach a “shared space”, in which all the pictures that have ever been painted regroup. The notion of time disappears. In painting, a hundred years is a short time. I always have misgivings about this word “contemporary“: what does it mean? I have seen roman frescoes that feel as if they had been executed yesterday.

Some art has simply fallen out of time.

Both: it stays in time, too. Because particular forms are only possible in particular times. I can only do my paintings right now in the way I do them, I think. 30 years ago, even if I had tried, they wouldn’t have made any sense. My desire is that my paintings have something from the now and something from the future both. Because it is beautiful to see wrinkles and scars, like it is the case for us humas.

Speaking about scars: you had a bike accident some time ago and could not paint for some time after that. How did you experience that period?

I was not able to paint at all, because movement was so painful. After four months, I was so annoyed… And I had an appetite, and certain visions. And so, I painted ten or twelve pictures, in my limited state, which are very reduced. It was easy to do these. Looking back at them, they had something prosthetic about them, like fragments of body parts - which I wasn’t really conscious of at the time.

And you stayed with it?

When my hand was much better, I thought that I would like to do more of these reduced paintings. But I couldn’t manage any more, because the inner cause was gone. It was a beautiful experience that the pictures themselves resisted it.

Did things simply continue after the reduced paintings, or did they continue to resonate?

They continued to have an effect in the sense that I just couldn’t continue with this process of reduction. I had skipped two steps of development. So I had to go back one step, which led me to fragmented figures. And then take another smaller step back, until I was able to concentrate on the whole figure again. The Happy Days paintings from my last show were a result of these “broken shoulder paintings”.

Taking two steps back sounds like an exercise in self-discipline - not allowing yourself to continue on a certain path…

Yes, but the path just wasn’t there.

And how did you realize that you needed to take steps back?

Because I stood in front of the canvas - and nothing happened.

And now the opposite: How do you know when a picture is finished?

That depends, and changes with every one of them, some need more time than others. The creation process can be compared to a whole life, from birth to end, and only then the picture is being born.

You are known for painting mainly in shades of grey and black. But here, I do see some colour, even if it’s muted. Where does this new colourfulness come from?

I have never seen my work as being black-and-white, and therefore I don’t see it as especially colourful now. It doesn’t make any difference to me. It was just the case that a window opened up for me, mainly by chance, because I had bought the wrong colours. I used them, and something happened, and I just went along. I see it as a whole. Colour didn’t interest me in the black-and-white pieces, just as it doesn’t interest me now.

In this painting, I do see some green…

This work will be the start of my show at mumok, in autumn 2025. It’s a reverberation of “The Blind leading the Blind” by Brueghel. I was interested in the fact that you can see the motive, while the motive itself (the blind) cannot see. But it is not supposed to be an interpretation of the painting, but more of a …

Starting point?

A starting point and a reverberation. The basic idea was to put more colour in the painting, but I liked the moment when you could only see the figures, with no distraction by a landscape, a church or anything else. And then: this empty canvas, so much white. The blind people, they don’t see anything either…

So you’re entering their world?

Yes. Of course, I have no idea how it feels to be blind. Maybe non-seeing has to do with energy or a sound, which help you to orient yourself.

And you caught the movement of falling in your painting…

This is one of my fundamental themes: falling and holding on. In the painting, it appears quite literally - one figure falls, and another one holds, one after the other.

Falling and holding on as a suitable theme for our times?

Yes.

Happy days was, as we have discussed, the title of your last show with Eva Presenhuber. It’s also a play by Samuel Beckett – how did you translate that into your work?

It had nothing to do with translating the play! A friend gave me the idea by chance, while I was looking for a title for the show. Happy Days - with a wink - would be a great title, I then thought. However, the paintings don’t relate to the drama, but to the general state that it’s about.

Therefore, did you choose the title after the work was finished?

I only ever choose the titles once the work is done.

What do you think about working in Vienna?

Ambivalent, I would say.

What are your new projects?

In autumn 2025, there will be the solo show at mumok. And there are two more solo exhibitions in preparation, one with Gisela Capitain in Cologne and a drawing show with Eva Presenhuber in Vienna, both in November.

Text: Alexandra Markl

Photos: Christoph Liebentritt