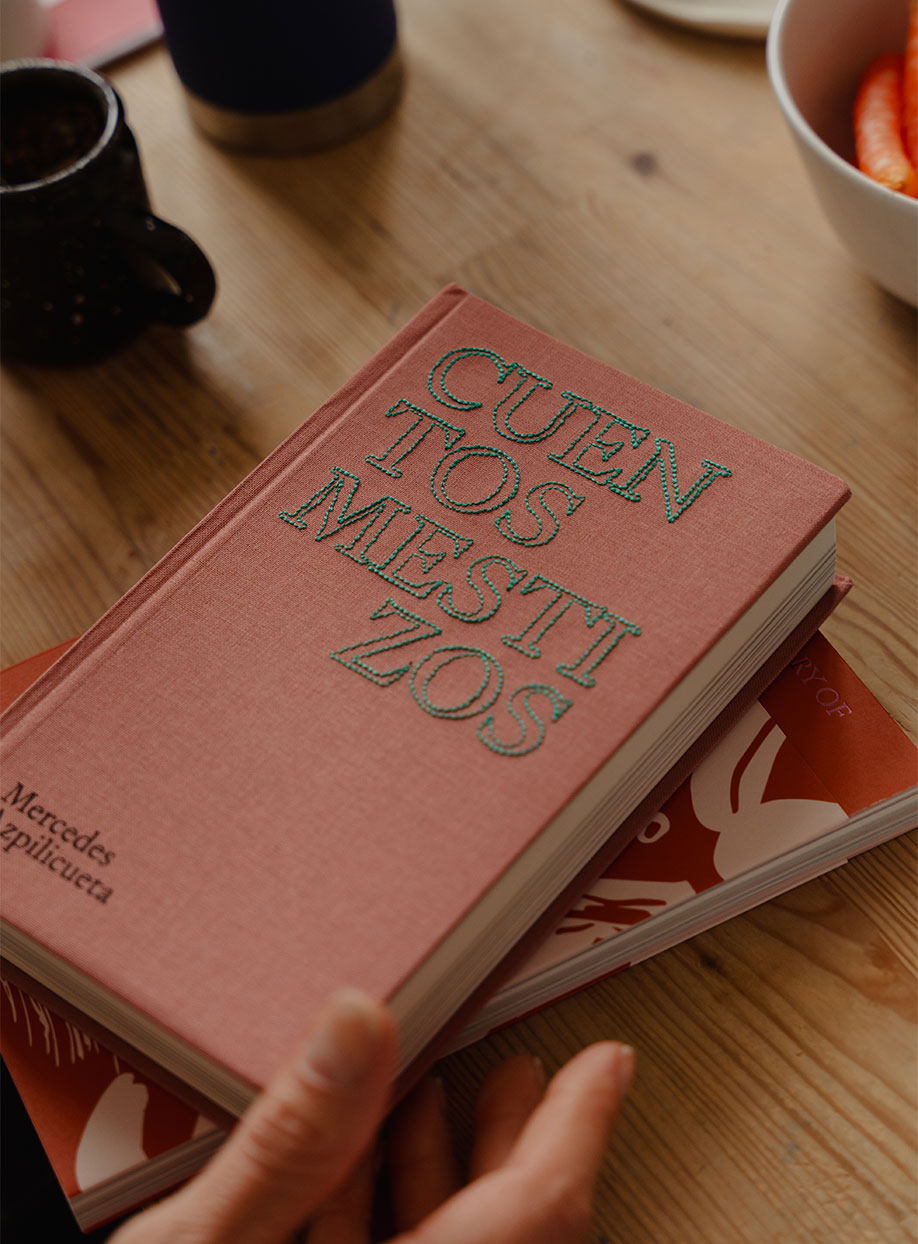

Argentinian artist Mercedes Azpilicueta doesn’t do straight lines. Her work spirals through half-heard tales, feminist theory, colonial histories, and the objects of her everyday life. In installations composed of textiles, sound, drawing and performance, she unravels dominant narratives to let alternative forms of knowledge come to light. Often beginning with a drawing, her process unfolds slowly, shaped by research, improvisation and long-standing collaborations. What emerges is a restless polyphony where the voices of dormant poets, mystics, and travellers gather not to form a single story, but to suggest another way of remembering: open-ended, alive, contradictory and unresolved.

Mercedes, did you always imagine your future as an artist?

Since childhood, I’ve always enjoyed drawing, but as a teenager, I began to consider art a real possibility. The path was quite labyrinthine. At the time, choosing art in Argentina felt almost reckless because the financial situation was so uncertain and scary. So I studied law and anthropology for a couple of years, but then the big financial crisis hit in 2001, and that path stopped making sense too. That’s when I finally decided to pursue art.

You moved from Argentina to the Netherlands over a decade ago. How did the move from Latin America to Europe affect your work and practice?

I displaced myself because I received a fellowship from Argentina for female artists. I wanted to work as an artist and experience something less traditional than the Buenos Aires art scene at the time. My practice was closely tied to writing, poetry readings, and publishing, but I didn’t feel it had its place or could evolve there. When I moved to the Netherlands, working across disciplines became a reality for me. I began writing more, making performances, and expanding my practice into voice and body. My work became almost ephemeral. The change of context also made me aware of the very different approaches to aesthetics. In Argentina, I was used to a lot of personal imaginaries, representations and symbolism. But here, in a Protestant context, art must be functional to a certain extent. With time, I also noticed that most Europeans often seem afraid to speak about themselves, particularly their feelings. It’s almost like: “You don’t go there.”

How did you find a way to connect your voice within that European backdrop?

Instead of looking towards my inner world, I started looking outward: to the city, to the streets. I went to street markets because they were the only places where people would be loud. People shouting, singing, and exchanging in so many accents and languages, all next to each other. The market was a space where people would express themselves in an embodied way and I thought: “This is material to work with.” Later, when I spent two years in Milan, something shifted again. I reconnected with my personal imaginary—with the Baroque, with representation, with emotion. I wanted to claim all of that back for me and my work.

So, today, how would you describe your work?

I work a lot with history, speculative fiction, and poetry. I mix them to revive stories that haven’t been told—real or fictional. But if I had to define my work today, I’d say it’s always held a certain absurdity. It’s unexpected, irreverent, playful, and attractive. I like that it’s visually seductive. I’m drawn to colour, scale, dimension, and light. My training was quite traditional, and I still go back to those foundations, but always thinking about how to twist them. To introduce disobedience. There’s always a beginner’s mind in my process. I like it when a piece holds a kind of primal energy. When you can feel that first spark.

Your pieces often feel like they are expanding and growing into many forms. There’s textile, performance, sound, sculpture…When you start working on something new, where do you begin?

I always begin with drawing and writing. That comes from Buenos Aires. There, I used to work with almost nothing because I could barely afford materials. Some pencils, maybe, but even paint was expensive. So, I would write or draw. That has always been my initial gesture. There’s something interesting in terms of economy. Anyone can do it with almost nothing.

I wanted to speak about textiles in your work. I recently came across an interview with artist Isabella Ducrot, who described textiles as travelling surfaces onto which human history and personal stories are deposited. It made me think of how you return to textiles in different ways. What have you found in textiles that speaks to you?

I have had a very personal connection to textiles from an early age. Growing up, my mom was a social worker and had a clothing store as a second source of income. I worked from the very beginning with her. We chose fabrics and made garments together. She had all these materials everywhere: wool, cotton, knits, leather. With her, I learned how to touch a piece of fabric, and what it transmits. She would design clothes and even organise seasonal catwalks, in which her friends, or my friends, as teenagers, would walk in them. It was such a joy to see her loving this world that involved dressing people. That store was our main source of income. It allowed me to study in Buenos Aires. My mom is the one who has always supported me, especially when I chose art. So textiles have both an affective and an economic layer for me. I guess that's why I have such a close connection to textiles. It is part of who I am.

You carried that legacy with you.

I kept working with them on and off, but when I was living in Milan, I found my way back to textiles and materiality. There, the connection to the fabrics is outside on the streets; it is everywhere, so present. I began longing for textures and costumes. That’s when I started working with natural silk and embroidery again.

And you always bring them into conversation with other mediums, too?

Yes, it's how I work. I really defend the right of female artists to be interdisciplinary. I think it kills the myth of the genius alone in the studio, chasing some perfect thing. I believe in disobedience as a way of making. Women are so tentacular, so versatile. I have a child, I work. I have to be resourceful, and women have always done that. I’m not a pattern maker, but if I want to create a complex costume pattern, I do it anyway. I do it with my own means, my errors and defects. That way of working, interdisciplinary and imperfect, has so much power. It requires flexibility. You have to negotiate with mistakes, with your capacities, in order to make something happen. For me, embracing different techniques, disciplines, and collaboration is a way of honouring women’s lineage.

In your installation Potatoes, Riots and Other Imaginaries, a beautifully woven Jacquard was shown alongside humble materials like crochet, scraps, and even cleaning cloths. What interests you about placing two different material values together?

I always try to bring different economies and different possibilities into the same space. When I work with Jacquard, that contrast becomes very apparent, given how technically demanding and costly it is to produce. But I like seeing art made with precarious materials. I need to feel that vulnerability that a material carries. That’s why I often work with cardboard, paper, and fabric samples. I always work with leftovers and objects at hand, even when I go to the lab to work in Jacquard, I work with scraps. I like assembling different kinds of materialities to tell a story. For example, in that same piece, next to the tapestry, there was a cap mixed with kitchen wipes. It resembled the kind of hat a maid would wear. It was almost like a reconstruction through assemblage. I take that from Latin American fantastic literature.

How so?

In Latin American fantastic literature, which is also called Magic Realism in Europe, you look at something, and at first, it feels familiar. But then, slowly, the unfamiliar, the oddness, reveals itself. That’s something I carry in my making. It also connects with Surrealism and Dadaism, which are important periods to me, as is the Latin American Baroque, which is not the same as the European one. The Baroque style travelled to South America with the Spanish and Portuguese to “civilize” Indigenous people and criollos. This, of course, was never fully accomplished. So the Baroque in Latin America became something very surreal. The local populations inserted their own artistic motifs into it; the virgins were black, and the angels had strange wings that looked like crocodiles or strange animals. It became this bizarre, excessive language. The failure of the Baroque is also the failure of Modernism. I like to work with those concepts, to create superpositions of meaning without one overriding the other. Things start to pulse. They become this kind of frantic rhythm.

Any Latin American books or authors you keep returning to?

There are so many. My poetry teacher, Laura Wittner. I often think about Un Beso de Dick by Fernando Molano Vargas. Also, Fabio Morábito. He’s Italian but writes in Spanish and lives in Mexico. Lately, I’ve been reading a book about María Elena Walsh, Nací para ser Breve, by one of her lovers, Gabriela Massuh. From Magic Realism, Elena Garro and Marosa di Giorgio are among the many wonderful writers I read. Mariano Blatt, who’s a close friend, is also an incredible poet. His work is really beautiful.

In many of your projects, you work with historical characters, mostly women, often shaped by contradiction and transformation. What draws you to these kinds of historical figures, and why do you feel it’s important to tell their stories today?

Many of these stories are linked to female makers. I tell untold stories of women who were often travellers, moved between cultures, spoke different languages, and most importantly, wrote. Characters that were ahead of their time. So I find it important to bring them back. The past returns and makes total sense in this very present. Sometimes it seems as if people are tired of those conversations. But when you walk through museums, the absence of these women is so palpable. That underrepresentation is still there.

I see myself in their stories. When I lived in Argentina, the art world was a very exclusive community. If you were a woman, you needed to come from a wealthy family or a family of artists to even stand a chance. Things change, yes—but very little and very slowly. I bring these characters back to live with them, to learn from them. I think maybe, sometimes, I want to be like them, too. As normal as my life might seem, I don’t want to live a normal life.

You have called yourself a dishonest researcher.

Yes, I think it’s our right to fool with history because we've been fooled by it.

There seems to be a strong feminist ethic that runs through your work. How do feminist perspectives manifest in your work as a whole?

I read a lot of things in relation to feminism. For me, it’s one of the ways of making and living differently. I’m not cautious about the word feminist. I think of my practice as that of a female artist who has had to deal with the inconsistencies of the cultural sector. We are paid less. Our works are acquired less frequently by museums and collections. We constantly have to justify why we do or don’t do things. We are mothers. So yes, I think it’s necessary—and very valid—to continue working towards a fairer reality for everyone. It’s always important to say that feminism is for whoever considers themselves a feminist. Especially now, with everything happening in the UK, the US, and elsewhere. So when I speak about female subjects, I’m speaking about whoever considers themselves one. The spectrum of womanhood is so wide.

Does this relate to your recent exhibition, An Art Student in Munich?

Yes! For some time now, I’ve been researching women artists who were connected to alternative practices like healing, spiritism, and mediumship—forms of knowledge-making that were often intersectional. Anna Mary Howitt is one of these figures. She went to Munich to study art because she was not accepted into the Art Academy in London. She wasn’t allowed to enrol in the Academy of Munich either, as it was forbidden for women to study art at the time. She still travelled there alone, which in itself was already unusual: a woman travelling solo in the mid-19th century. Eventually, she was given space to work in the private studio of the academy’s director. She was also a great writer and wrote An Art Student in Munich, where she elegantly describes her daily life in the city, including her friendships with other women artists.

For this exhibition, I made a series of modular sculptures that represent them—the sisters, and her friends. I started with easels for the structure because it’s all about the work in the studio and looking into how these women worked in art. I really wanted to look into their domestic environment as makers. I created these kinds of characters that are a bit anthropomorphic. All the parts of the sculpture can be dismantled and reassembled. I wanted them to be interchangeable, as a reflection on sisterhood and solidarity.

In that vein, you often work closely with collaborators, writers, designers, and performers, many of whom you’ve worked with for years. What have these long-term collaborations taught you?

What I have learned is that the end is not to make the work, but rather to develop a relationship, to create an experience. That is what I want to learn when I make something. I want to learn from that moment, from others, not from an object that is finalized. Those collaborations often turn into friendships; it is more than just working. It’s a soft infrastructure.

Finally, what are you currently working on?

I’m working on a project that’s not exactly for children, but it’s non-adult-centric. It’s about the theory of play. It explores the right to play and how it connects to the studio and the creative process. When we play, we lose track of time—five minutes, three hours—it disappears. That also happens when we make art. It’s a non-chronological time, what the Greeks call aion—the intense, immeasurable time of childhood. I want to reclaim that space in the studio.

Art has become so rational and goal-oriented. I want to claim a non-productive space—where we don’t play to learn, but simply to play. In medieval times, playing was about intergenerational community and absurdity. That ties back to imagination, which is at the core of what I do. I’m focusing on two play theories: one on imagination and another on community, ritual, identity, and memory, like carnivals and collective feasts. We’ll see where it takes me, but I’m really enjoying it.

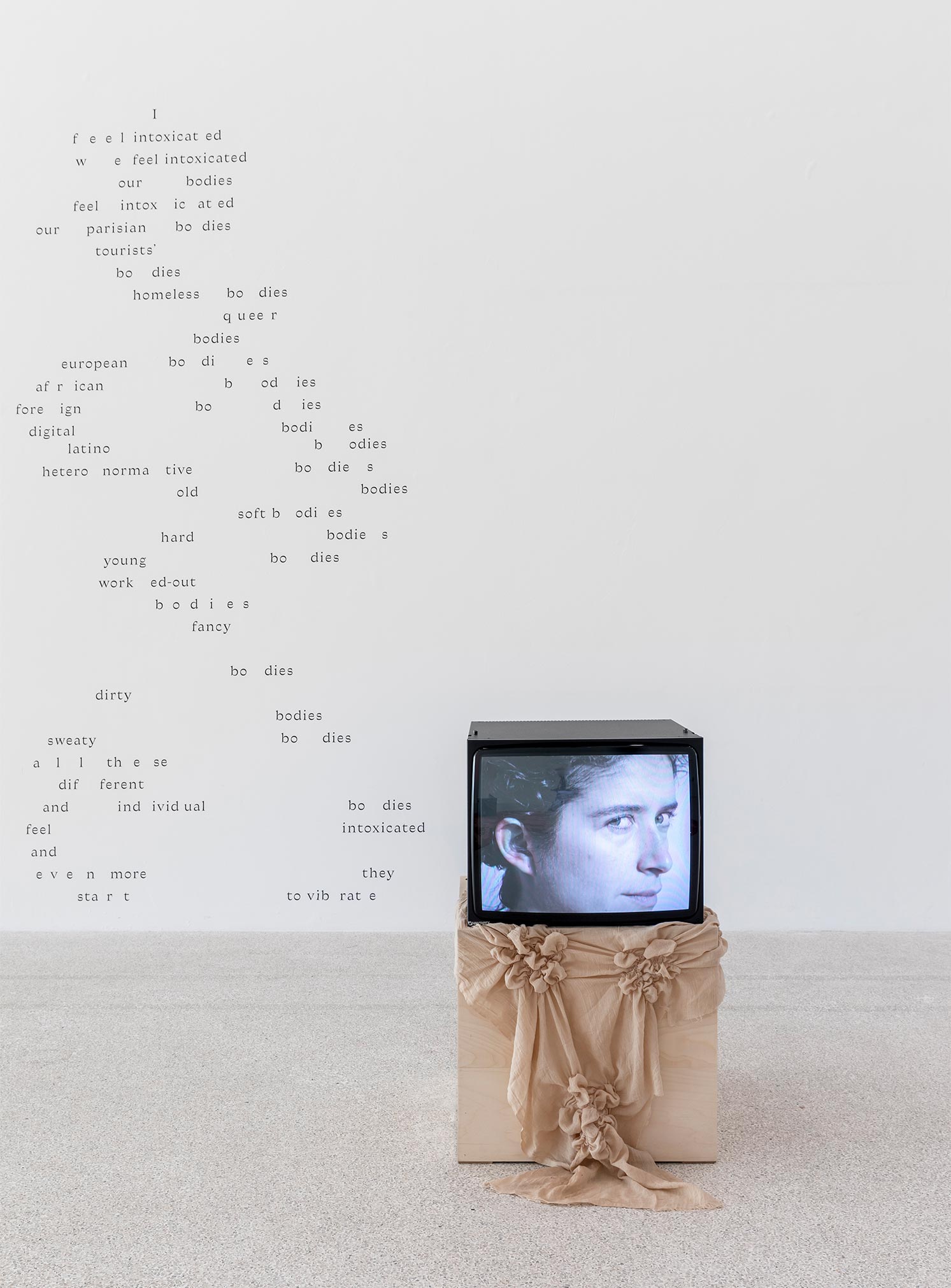

Mercedes Azpilicueta, Bestiario de Lengueitas /Bestiary of Tonguelets, 2020. MUSEION, Bolzano/Bozen, Italy. Photo: Luca Guadagnini

Mercedes Azpilicueta, Bestiario de Lengueitas /Bestiary of Tonguelets, 2020. MUSEION, Bolzano/Bozen, Italy. Photo: Luca Guadagnini

Mercedes Azpilicueta, Potatoes Riots and Other Imaginaries, 2021. Prix de Rome, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Photos: Daniel Nicolas

Mercedes Azpilicueta, Potatoes Riots and Other Imaginaries, 2021. Prix de Rome, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam. Photos: Daniel Nicolas

Text: Maria Paris

Photo: Georgina Abreu