The past and the present collide in the works of Nikita Kadan. His works reflect the historical paradoxes and conflicts of collective memory and trauma in Ukraine, responding to the ongoing war with Russia. Born in 1982, Kadan was part of the Revolutionary Experimental Space (R.E.P.) and co-founded the activists’ group Hudrada, working with architects, sociologists, and human rights activists. He now works as a solo artist through various mediums, including drawing, painting, sculpture, and installation. Kadan’s manipulation of monuments and archival material questions the possibility of neutral, objective coverage of events, calling attention from an international audience to the atrocities and fascism surrounding his home in Kyiv.

Nikita, what were your artistic beginnings?

It’s complicated to landmark your beginning living in a place where an institutionalised system is not developed. My first turning point was when I was fourteen or fifteen. I went to the school library to get some books on art history. This was in the 1990s, in Kyiv, when almost nothing was published on international art. There were no big, nice art books, glossy ones with high quality printing. Especially nothing on modern and contemporary art. But I took one book, published in the USSR in the early 1980s, called “Modernism”. It was a Soviet writing on art, a highly ideological, Marxist critique of Western modernist art. Starting from artists like Marcel Duchamp and ending with conceptual art. I got this feeling that I want to do things like that. I want to become an artist, but not a traditional artist.

A second turning point was in 2004, when I was an art student at Kyiv Art Academy, a very conservative Academy with the Soviet kind of teaching. There were huge protests on the Independence square against falsified elections. I participated in this with my friends, and we made political posters in the form of huge expressive paintings on the cheap cloth which we started to exhibit in the street. The director of the Soros Centre of Contemporary Art proposed to use the centre as a workplace, and later we made a show of these works which was like an open studio. We started to make works of a totally new type, and we found ourselves as young, politically-engaged artists. Some of our works were exhibited abroad and we found ourselves inside of this “professional art system”. But I still consider myself to be a very local person with a very local experience.

What impact does your local experience have on you?

I am based in Kyiv, there was a big missile and drone attack this night. I was very sleepy and I heard one explosion and then I just slept and didn’t wake up. In the morning I read about how many people were killed and injured, and I knew that while I was drinking my coffee there were still people under the rubble, an hour’s walk from my house, and some of them will be saved and some will die. This is a daily routine. I am used to working under these conditions. It’s not like turning insensitive totally but rather having a “postponed sensation”. We’ll mourn them tomorrow. We’ll mourn ourselves tomorrow maybe.

How has your art changed in response to that?

My path started from political work. In 2009-2010 I made a work called Procedure Room about police torture in Ukraine. When in 2014 Crimea was annexed and the war started in Donbas, my works already were about traumatic experiences of society, about the collective pain. So when in 2022 a war came into my house, not that much changed in fact. In 2014 my works, which were openly political already, got this historiographical dimension. I started to work with the images of the past. In this sense I’m addressing some non-existent, utopian, universalist, and critical historical museum. A museum which is not dependent on any national vision of history and is not based on any nationalist ideology. It's an imaginary museum. But now this museum turned into a court, and this process of history writing turned into a trial.

How did it change in terms of content?

I’m used to working with these zones of social vulnerability, with themes of conflict and struggle. Before 2014, it was about the war of the state with its own citizens. Or the war of late capitalism with the leftovers of the social state. Now there is an enemy from outside, a fascist Russian regime. And now one of the big open questions for Ukrainian artists is what we should do with internal critique. Isn’t it like criticising the victim at the moment of violence? Or the victim has the right to criticise themselves? But what does this critique mean in the eyes of the others? Is it “critique as usual” or something different?

How does reference to history come into that?

Things from history books come so close to what is happening now, and some things which are happening right now might be in the history books of tomorrow. But if Russia wins, history will be written in a totally different way. Also, if this global extreme right-wing turn will dominate public discourse, there will be a different history. “Alternative facts”. It really depends on us now, what history will be. Just in the last few weeks, one of the most brilliant artists of the young generation in Ukraine, Margaryta Polovinko, who was fighting on a frontline, was killed. I was at her funeral. She is a part of Ukrainian history already. There is this non-distinction between history and the present. I work with historical documentation and commemorative practices. I think of struggles around images, like photographs of civilian victims in Volhynia, from western Ukraine from 1943, when there was a big ethnic cleansing of the Polish population committed by Ukrainians. And then the mass murder of Ukrainian civilians committed by the Polish side in revenge. There are still fights around these photographs, like who are there? Polish victims or Ukrainian victims? Who is the victim? Who is the perpetrator? These photos are not just a history, which is neutral. These images are a part of the struggle now. You can imagine the intensity of the struggle around documentary images or any historical documents which relate to Russia and Ukraine. Everything is a battlefield. The archive is a battlefield. Historical museums are a battlefield. They are directly connected with the real battlefield, where people are dying at the moment. The same thing with the monuments, and with public spaces. In the Western world, there is verbal debate about the removal of monuments with activist campaigns and so on. But in Ukraine, if the monument doesn’t fit into the changed political agenda then it is destroyed immediately.

How do you work your critique into different artistic mediums?

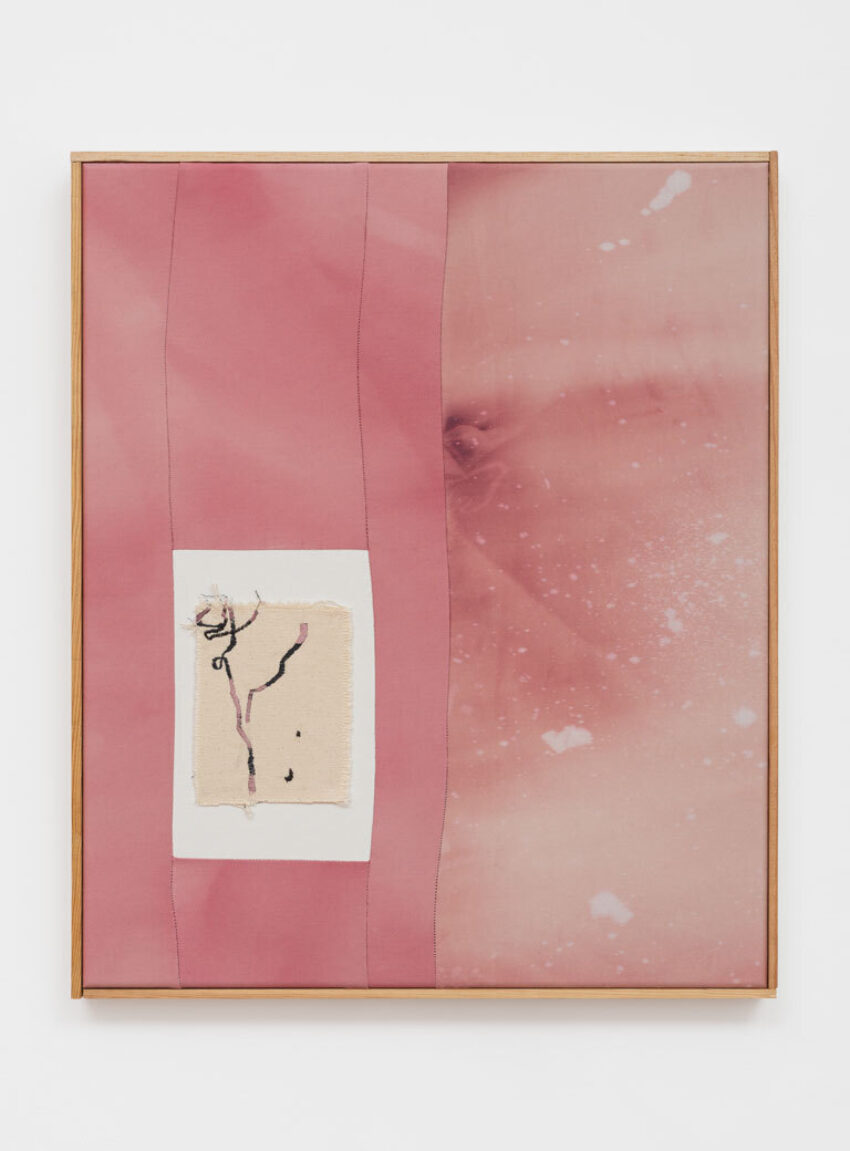

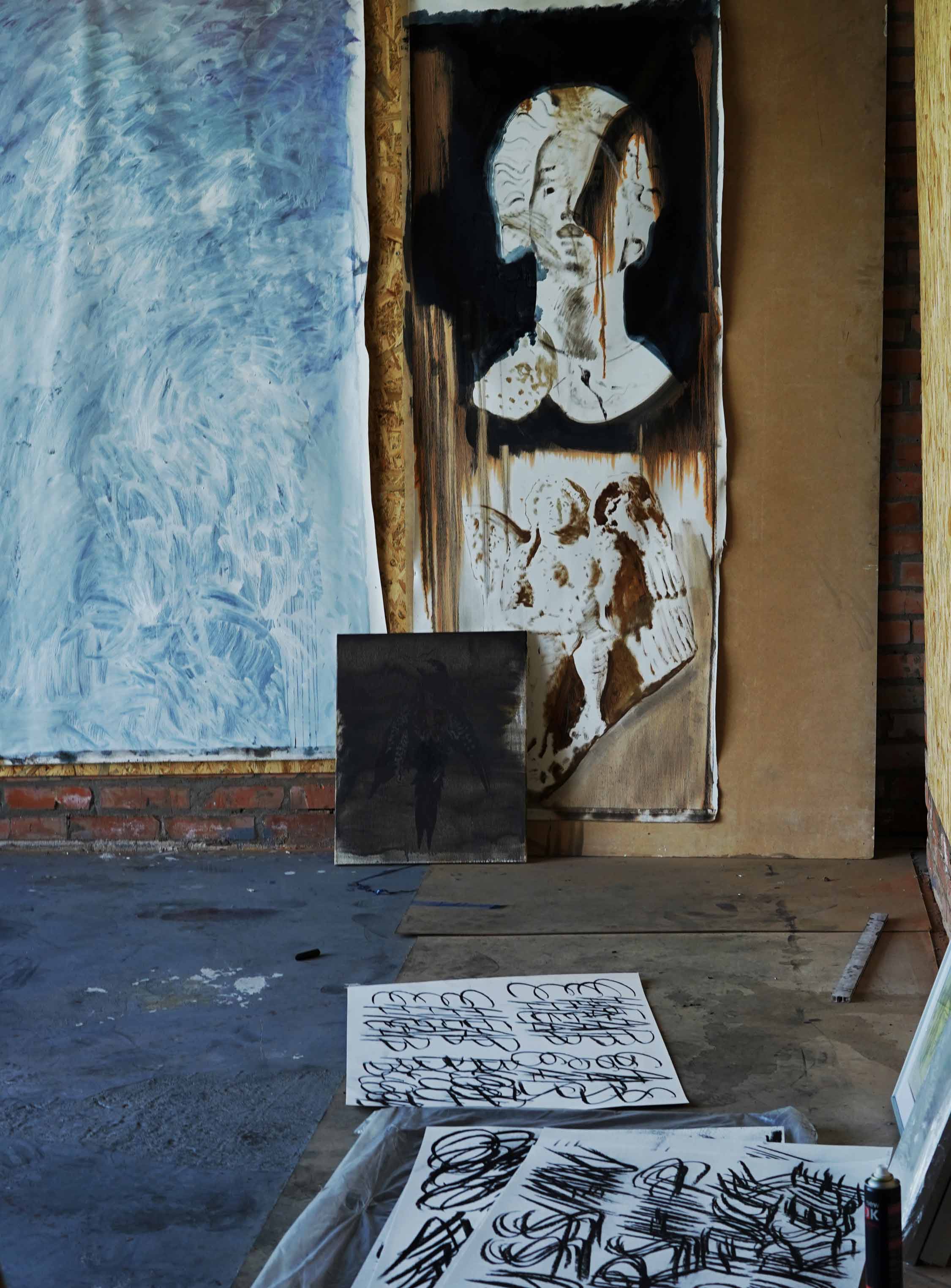

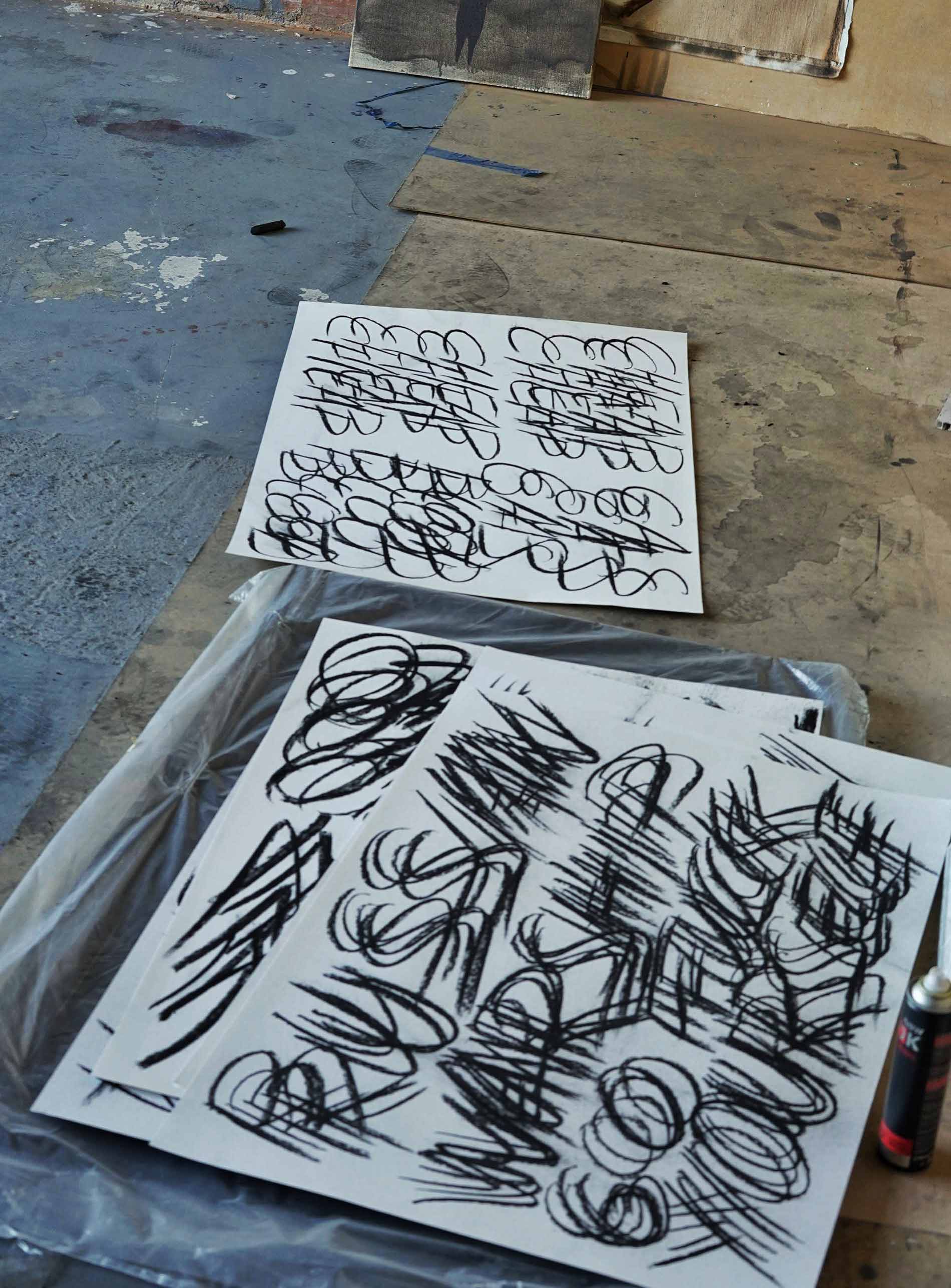

I am using both so-called traditional and new mediums. I use figurative charcoal drawing very often—especially in connection with black-and-white archival photography. I use ready-made objects, always in relation to the political context they are taken from. When I use archival materials, I see them as part of the current political struggle and debate. So even when I use something from the past, it is about the present. It is about the impossibility to use something in a neutral and distant way.

Are you being commissioned to create your works?

Often there are site-specific works. In Europe during the war I’m often thinking about the context, the local context, and its relation with the Ukrainian situation. It’s always about what part of Ukrainian experience could be brought to a different place, and what changes. What are the relations between Ukrainian experience and this place? The work which should be at mumok during the exhibition which opens in May is like a second version of the work which was made for the Kyiv Biennial, an edition which took place in Vienna. By then I was invited to do something in relation to the controversial Karl Lueger monument in Vienna, but finally my work was shown at the exhibition venue, not at the square, as it was planned before. I was interested in the role of the ideological symbols, their presence in the public space through different historical periods and the consequences when time changes. Keeping symbols or removing symbols. Protecting monuments as some sort of cultural heritage, or leaving them to advocate certain values. What happens when these values are found to be ‘on the wrong side of history’? I took an image of the Soviet monument in Hostomel, a WWII monument which was heavily damaged by Russians. But Russians claimed that they came to protect these kinds of monuments from Ukrainian nationalists. To protect the common historical memory of Russian and Ukrainian people. According to Russian propaganda, such monuments were destroyed or removed in Ukraine. In reality this monument just stood in the middle of the Ukrainian town and people brought flowers to it and treated it with respect. But, paradoxically, after the invasion, these sorts of WWII monuments are officially destroyed in Ukraine because they are already considered to be pro-Russian symbols. But—another paradox—it seems that this monument will stay because it keeps traces of Russian violence and Russian crimes on its body and face. When fascist Putin’s regime claims to fight fascism in Ukraine, it might seem absurd, but it helped a lot to whitewash the Russian military aggression in the eyes of many westerners. Extreme violence comes hand-in-hand with the enormously fluid rhetoric.

How has collaboration played a part for you? Do you mostly work as an individual artist now?

I work mostly as an individual artist now, but sometimes in dialogue with different artists and non-artists. I started as a member of R.E.P., and I had experience of collective curating with Hudrada. I have had a number of collaborations with writers, architects and historians as well. I was used to initiating different artistic collaborations in previous years, and now I'm turning more into a single figure with my individual experience of surviving this period in Ukraine.

What benefit does that have for you?

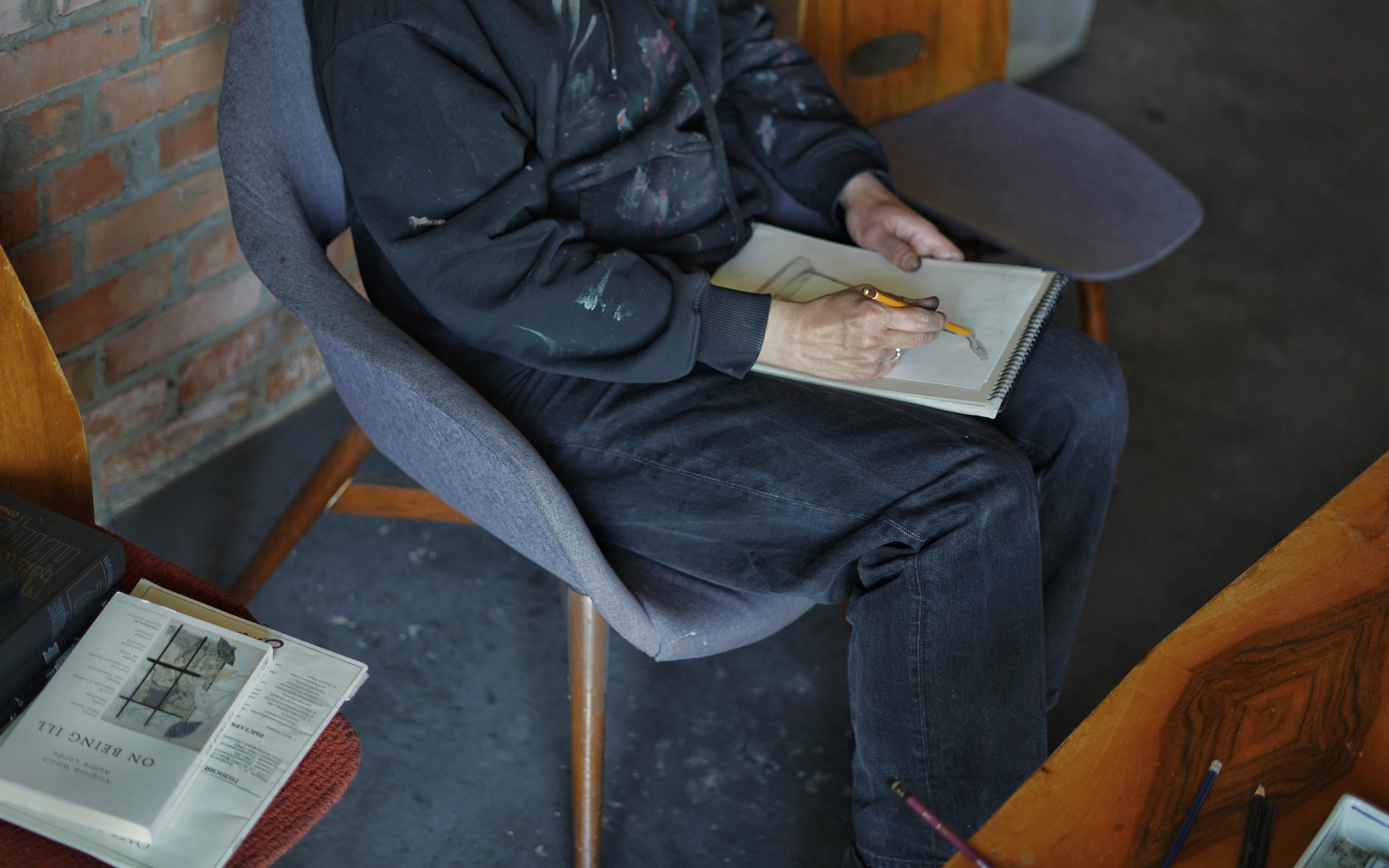

Sometimes it’s better not to share the responsibility with others, to take full responsibility for the statement myself. It brings a symbolic risk which turns into this practical, material risk. Risks can be beneficial. I am becoming more intuitive as I get older, and there are things related to the creative process which are not that easy to share with others. When you are younger, you are more open to different kinds of discussion. But never say never, maybe there will be some different artistic collaborations in the future.

What are you hoping to achieve with your art, with people who are interacting with it?

I’m used to seeing a distance between what I’m actually doing and other people’s perception. While doing the work I’m not thinking whom I should address it to. Artists address many audiences, and if an artwork will exist in the future we wonder what perception it will meet, what values these people will have, what language they will speak, what they will look like. I don’t know. I don’t like to be in any “target group”, but rather to be a “witness of art”. I am showing war experience at peaceful places to let people feel the fragility of the border between war and peace.

What has that process been like during the war?

Working here during the war, at the place of war, but still going on with this post-conceptual kind of artistic practice, which demands a certain distance, is always a paradox. Urgency doesn’t accept distance. But I try to create these unstable constellations of urgent and distant elements. Except for the public part, there are much less visible things behind representing art from Ukraine, like the fact that Ukrainian men are not allowed to travel, or their short-term travels are strictly controlled by the state. There are Ukrainian voices which you hear and there are ones which don’t have a chance to reach your ears. If artists are restricted in their mobility, they are not on the same ground with many international colleagues, but they still exhibit together with them. Wartime has its materiality, and it creates limits which are not visible for others, who live outside war. All this makes an impact on art. But you have to do your work in the most intense way. You just have to do your best. But if you do it under current material conditions, you can never forget about its gravitation.

Interview: Lillian Crawford

Photos: Olgiver Twist